Once again, Israeli-Palestinian relations are at an impasse. Unlike myriad previous times, however, many on both sides and in the international community are giving up on the possibility of conflict resolution in the near future. Many are even rethinking their basic assumptions about whether and how this conflict might be resolved. Thirty-seven years since Camp David and 22 years since Oslo, seemingly all avenues for progress have been tried: international conferences, bilateral or trilateral negotiations, mediated proximity talks, autonomous Palestinian institution building, and unilateral Israeli withdrawals, all to no avail.

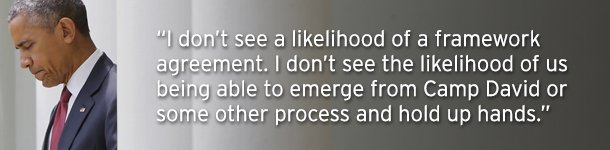

What now then? While some in the State Department still hope to revive direct negotiations for a final status agreement now, President Obama recently stated publicly, in an interview with Ilana Dayan of Israel’s Channel Two, that “I don’t see a likelihood of a framework agreement. I don’t see the likelihood of us being able to emerge from Camp David or some other process and hold up hands.”

Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

This impasse results in a series of policy dilemmas, each presenting a need to balance between short- and long-term goals: preserving the possibility of conflict resolution through partition, likely in a two-state solution, and the dire need to improve conditions in the interim. Should the parties, and the United States, try to steer the ever-shifting status quo toward future resolution, or should they focus on avoiding the resumption of large-scale violence, with its immediate devastation and long-term damage?

Below I sketch four of these dilemmas:

Should Israel deal with Hamas, against the wishes of Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, in order to ease conditions in Gaza and stabilize the situation there?

Should Israel deal with Hamas, against the wishes of Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, in order to ease conditions in Gaza and stabilize the situation there?

How much deference should the United States and Israel accord Abbas, with the end of his reign looming? How should they prepare for the day after Abbas?

How much deference should the United States and Israel accord Abbas, with the end of his reign looming? How should they prepare for the day after Abbas?

With the prospect of long-term resolution now distant, should the United States continue opposing any interim steps, coordinated or unilateral?

With the prospect of long-term resolution now distant, should the United States continue opposing any interim steps, coordinated or unilateral?

How should the United States deal with the growing Palestinian effort to internationalize the conflict? Should the United States put forward its own plan on the international stage, as the administration has considered?

How should the United States deal with the growing Palestinian effort to internationalize the conflict? Should the United States put forward its own plan on the international stage, as the administration has considered?

Each of these dilemmas pits the long-term, the viability of future—perhaps distant—conflict resolution, against immediate policy considerations.

Gaza, Hamas, and Abbas

The source of most recent misery in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains largely unchanged: the stand-off between Hamas, in control of Gaza Strip, and Israel, blockading the Strip. The ideal solution, to my mind, is clear: Hamas would disarm and Israel would lift the blockade. That is very unlikely to happen.

Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Mohammed Salem

Hamas has wrought tremendous damage to the now-moribund peace process, to Israeli civilians, and most of all to those Palestinians whom it governs and drags to war with a superior power every few years. I find thoroughly unconvincing the suggestions that Hamas may moderate such that it could emerge as a partner for a two-state solution. It belies Hamas’s long track record in the West Bank and especially in Gaza, not to mention Hamas’s own repeated statements of principle. Some in Hamas may of course accept a state within the 1967 borders, but even they don’t claim their demands, or their fight, would stop there.

If there were a responsible way to remove Hamas from power, I would suggest considering it seriously. Unfortunately, given the balance of power in the Strip, the emergence of Salafist elements in Gaza that out-terrorize Hamas, and, most importantly, its solid base of support among a large segment of Palestinians, I do not see a responsible way to do so. Hamas is, of course, not only a militia, but also a political party with political incentives that can be leveraged. It is a dismal reality to be dealt with, but it is not beyond the realm of geopolitics.

This logic now appears finally to have gained traction among the Israeli political leadership. Urged by the military, the political leadership has been easing restrictions on Gaza and is likely ready to ease them further if security arrangements could be found, with active U.N. brokering already underway. A long-shot possibility of an informal Israel-Hamas ceasefire has even emerged. In such a scenario, Hamas would limit its re-arming and the construction of tunnels into Israel’s territory (tunnels that have no conceivable non-military purpose) and Israel would significantly ease the restrictions on the movement of people and goods in and out of Gaza.

Indeed, since the conflict in the summer of 2014 there has been a quiet sea change in the Israeli approach to the Gaza Strip, led by security officials. Whereas before the conflict, Israel vociferously rejected a nominal unity government between Fatah and Hamas, Israel now appears to accept, begrudgingly, Hamas’s role, though it is still unlikely to accept a unity government in which Hamas is included. Even hardliner cabinet member Naftali Bennett seems open to this possibility: After criticizing Prime Minister Netanyahu during the last conflict for not bringing down Hamas, Bennett has now argued that Israel should, for the time being, acquiesce to Hamas’s rule and ease economic conditions in the Strip considerably.

Partial Israeli accommodation of Hamas, however, though good for the Palestinians and the Israelis in the interim, would be politically harmful to Abbas. It could be construed by the Palestinian public as a vindication of Hamas’s decision to pursue—and especially to continue—the war in 2014 long after repeated cease-fires had been brokered. The armed struggle would seem to some to have achieved what negotiations could not, as preposterous as this perception would be. (If Hamas had not decided to fight Israel from the evacuated Gaza Strip, there would not have been a blockade or recurrent conflicts to begin with. Note, for example, that by refraining from war, the West Bank has so far avoided much of the misery of Gaza. It was Hamas’s wars, not Fatah’s negotiations, that brought about Gaza’s misery.)

Indeed, even if Israel and Hamas were to go toward a tacit agreement (still a long shot), two actors remain to be convinced: Egypt and Abbas. The former has maintained a hostile posture toward Hamas due to its connection to the Muslim Brotherhood, and has closed off the Gaza Strip tunnels to the Sinai. Now, Egypt finds itself in an intense battle with ISIS-affiliated groups in the Sinai, at Gaza, and Israel’s doorstep. Abbas, perhaps buoyed by Egypt’s stance, has refused since last summer’s conflict to facilitate the reconstruction of Gaza, let alone the opening of the Strip (which would likely require his troops to man the border crossings), an irresponsible position for the nominal president of the residents of Gaza.

The policy dilemma is therefore between short- and medium-term goals: work to avoid a repeat of the summer of 2014 or promote the long-term interests of resolution, which lie with Abbas and perhaps with his successors, not with Hamas.

This is not a simple dilemma. Deal with Hamas, and there could be real long-term damage on other fronts. Avoid Hamas altogether, however, and a repeat of the conflicts of 2008 to 2009, 2012, and 2014 is quite likely. To my mind, the possibility should at least be explored seriously.

Abbas the indispensable?

Abbas and his regime are critical not only for putative negotiations down the road, but to prevent full-scale violence in the West Bank. Currently, the simmering violence against both Israelis and Palestinians is held at bay not only by the vigilance of the Israeli security forces, but by the close security coordination between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) forces, despite the political impasse.

Indeed, in one incident during the Gaza conflict in the summer of 2014, Fatah militants boasted of firing live ammunition during a demonstration against Israeli soldiers at Qalandia, between Jerusalem and Ramallah. The next day, a Friday and the holiday of Leilat al Qadr during Ramadan, the stage was set for clashes that could bring the fighting from Gaza back to the West Bank, where it had begun. It was the notable discipline of the official PA security forces—many of them Fatah people themselves—that prevented dramatic deterioration by creating a physical buffer between the demonstrators and Israeli troops.

This cooperation comes under considerable (and rather cynical) political fire, since it also benefits Israelis. Such criticism, however, not only discounts the value of Israeli lives, but also those of Palestinians, the weaker party that suffers more from violence. Despite his many shortcomings, Abbas has succeeded in avoiding the devastation of war in the West Bank, something neither his predecessor nor his rivals in the Gaza Strip could claim. The security cooperation has been at the heart of this success.

The question remains: Will the cooperation survive Abbas? How best can this be ensured?

Photo courtesy of REUTERS/ Eduardo Munoz

Abbas now displays neither youth (he is in his 80s), robust health (a heavy smoker), nor the dynamic energy required of a leader in difficult times. He has repeatedly threatened to resign and is committed not to run in the next elections, if and when any are held.

How much deference, therefore, should Abbas receive as Israel and the United States each weigh their policy options? He offers the best hope for avoiding catastrophe in the short-term, but apparently little in the way of a path forward. Fostering relations with potential successors—Abbas has avoided appointing a vice president—also risks alienating Abbas, something the United States in particular has been loath to do.

Abbas is a known and responsible partner for both the United States and Israel, but he is a lame duck in all but actually facing a clear end to his term. The United States and Israel must prepare, with the requisite diplomatic sensitivity, for the day after his presidency.

Back to the incremental approach?

A focus on the long-term led the Obama administration to adopt the Palestinian opposition to interim arrangements of any kind. If interim arrangements are reached with no final status agreement in sight, Palestinians have argued, such arrangements would only become permanent.

Since Ehud Barak set out to Camp David in 2000, he and others in Israel have argued that Israel should not wait for a partner for full peace—which many Israelis believe is absent—but rather take matters into its own hand and draw provisional borders. The Quartet Roadmap for Peace, led by the United States, indeed envisioned a Palestinian state with provisional borders. Sharon’s unilateral “disengagement” from Gaza and the northern West Bank a decade ago was, for some like then-Deputy Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, the start of a broader move to disengage from significantly more of the West Bank as well.

An incremental approach could offer tangible benefits to both sides, easing conditions on the ground and allowing for further Palestinian contiguity and economic development. It has severe drawbacks as well. If done unilaterally, interim steps can greatly diminish the standing of Israel’s putative partners for future peace and embolden Hamas, which would argue, again, that its violence had driven Israel out. Military redeployment could allow Hamas or even more violent groups to take over, as in Gaza. Indeed, more than any other incident, Israelis cite the Gaza disengagement as proof in the futility of concessions to the Palestinians.

Photo courtesy of REUTERS/ Jason Reed

To my mind, however, with no other way forward, the notion that nothing should be done in the interim for fear of losing the (absent) way forward, is misguided. Interim steps, including evacuation of remote settlements, need not entail military redeployment nor must they be unilateral, provided a Palestinian leadership were willing to coordinate. They could allow for a tangible easing of conditions and a change of momentum away from deepening conflict.

The business of real peace in fact often involves imperfect, partial steps. To be sure, such interim steps must not prejudice the broader goal of peace down the road—a policy consideration that considerably limits the menu of interim steps. Interim steps should not provide cover for moves by either side that will further close the window on conflict resolution. But it is worth remembering that the alternative to interim steps—the current course—hardly fairs better by this measure.

The international arena

The impasse in Israeli-Palestinian relations has led the Palestinians and others to the last arena where they are strongest—the international one. There have been several initiatives to introduce Palestine as a member state of international bodies such as the United Nations or to set timelines for the (woefully un-derspecified) “end of occupation.” These have been accompanied by a growing public push to boycott, divest, or sanction not just the Israeli presence in the West Bank, but also Israel itself, Israeli individuals, or, when bigotry is most apparent, non-Israeli Jews.

The problem is, of course, that ending occupation is not as simple, nor as well-defined, as it sounds. Ask the peace mediators that tried to resolve the conflict over the past two decades and more. Occupation is surely unjust, but it is not nearly the sum of the conflict nor would ending it end Palestinian claims. Justice always seems simple to either side; peace, alas, is not.

The main policy dilemma for the United States has been whether to preempt some of these initiatives and publicly outline the framework agreement arrived at by the U.S. negotiating team in 2014, as the president and the secretary of state have contemplated. Such a public framework—as a Security Council resolution or a presidential statement—would have the benefit of capitalizing on the work done by this administration and serving a policy focal point going forward. It might help cement the idea of a two-state solution and stave off some of the more pernicious alternative ideas out there.

Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Pool

Neither side would likely endorse a detailed framework however. It would necessarily include language—especially on Jerusalem—that this Israeli government would never agree to and that no Israeli government would agree to outside the context of a full, mutually-accepted accord. Similarly, the Palestinians are sure to object to much of the framework (Abbas, after all, never replied to the framework agreement presented to him), especially on a return of Palestinian refugees and descendants or on ideational reconciliation (the Israeli demand that they accept Israel as a—underspecified—Jewish nation state.)

In other words, publishing a framework for a two-state solution before Obama leaves office could offer a basis for long-term gains in future conflict resolution. Doing so, however, would also increase the possibility of the short-term danger of each side painting itself further into its corner on the very issues the framework hopes to resolve.

Long- and short-term

During the years of the active peace process, balancing long-term and short-term goals could appear relatively simple: avoid catastrophe just long enough for a final status agreement to be reached. In the current impasse, a deal does not look likely any time soon. Accordingly, the main policy challenge now, in my view, is balancing two different goals: active conflict management, with modest goals, and keeping the door open to conflict resolution in the future.

In the four policy dilemmas noted above, efforts should now be made to avoid the worst outcomes—widespread violence in particular—and to normalize the situation, without excessive concern for the chances of immediate resumption of negotiations. Thus, Israel and the United States should vigorously explore a modus vivendi in Gaza, despite Abbas’s objections, while working to persuade him to live up to his responsibilities as president in Gaza. He, not Hamas, should receive as much credit as possible for the benefits of such an arrangement, but he should not be allowed to prevent one for fear of the responsibilities it would entail.

Further, the Palestinians themselves will have to choose their next leader, but it is high time to face the reality that that day is not far; Abbas will not likely be the first president of an independent Palestine. Policymakers would do well to prepare for that day, and put less stock in—and pay less deference too—Abbas the man.

Managing the interim also means that any steps that can normalize the situation—including physical Israeli redeployment or transfer of authority to the PA in parts of the West bank—should be encouraged, provided they do not prejudice the long-term goal of partition. The interim is likely to last a while regardless of present policy; it should be made as manageable as possible.

Finally, while publishing a U.S. framework agreement now is likely to meet stiff resistance from both parties, the damage will likely dissipate long before serious negotiations are resumed. Key principles could therefore be set forth as useful long-term goals to which all parties can, in time, recommit, and with which all short-term steps should be made commensurate.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Dilemmas of the Israeli-Palestinian impasse

September 17, 2015