The May employment numbers broke from the positive news of the last few months and revealed weakness in the job market. According to the Labor Department, payroll employment increased at its lowest rate in eight months, as employers added just 54,000 jobs. Private employment edged up by 83,000, while government employment fell by 29,000. And the unemployment rate ticked up for the second straight month, to 9.1 percent.

Not surprisingly to most Americans, these numbers indicate the job market remains tough—particularly for the nation’s young adults. College seniors graduating this spring will enter a job market vastly different than the one that existed when they started college. Indeed, when the Class of 2011 first enrolled for classes, the unemployment rate was below 5 percent.

In this context, there have been a series of recent news stories documenting the challenges facing recent college graduates in their job search. This has triggered new debate about the value of a college degree in the current economic climate. Are today’s college graduates really better off than their counterparts who did not invest their time and money in a post-high-school degree?

For this month’s posting, we examine the most recent data on young adults age 23-24—the “Class of the Great Recession”—to show whether those who chose college are better off in terms of both their employment prospects and earning potential. We also continue our look at America’s still growing “job gap,” or the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

How Recent College Graduates Stack Up

In a normal economy, more education generally means lower rates of unemployment. That being said, America’s younger workers have been hit harder by the Great Recession of 2007-09, regardless of their education. Past Hamilton Project job blogs have highlighted the importance of a good education for employment prospects, and the disproportionate impacts of the recession on America’s youth.

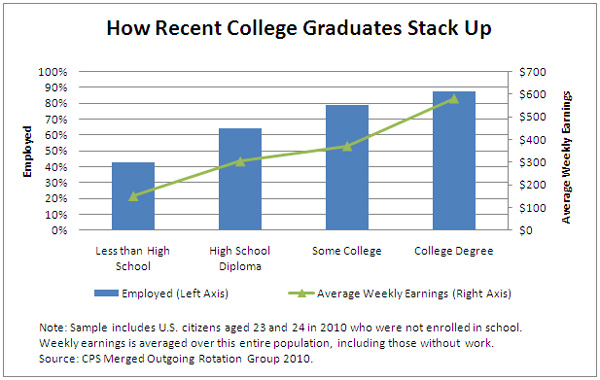

Data from a sample of the youth population in 2010 helps illustrate the advantages of entering the post-recession economy armed with a college degree. The chart below shows the employment (blue bars) and average weekly earnings (green line) of all 23-24 year olds who were not attending school in 2010. As we see in the population, the differences in employment outcome by education are significant.

Those with a college degree are in significantly better shape than their peers, with 88 percent of college graduates employed in 2010. And, in addition to having a better chance of finding a job, they are making more money. The average weekly earnings of those with a college degree was almost double the earnings of those with only a high school diploma, at $581 versus $305.

Young adults with some college had an average employment rate of 79 percent. Those with only a high school diploma had a much lower employment rate of 64 percent. Young adults without even a high school diploma fared far worse—only 43 percent were working.

The May “Job Gap”

Unemployed recent graduates are just one group represented in our “job gap” estimate of 12.1 million jobs.

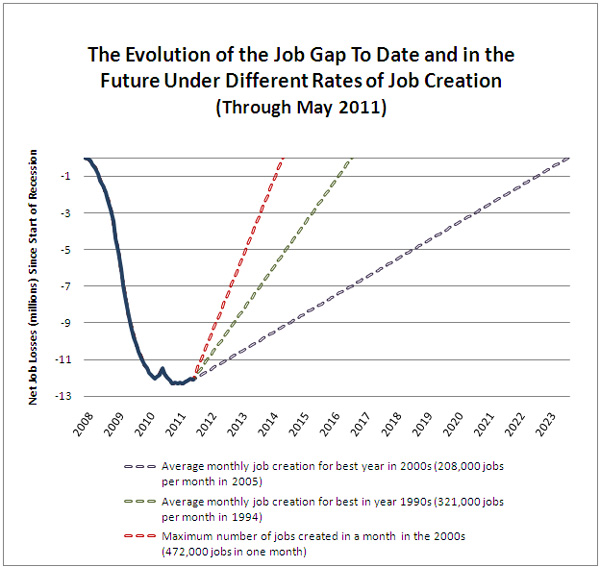

As in previous months’ postings, The Hamilton Project updates America’s job gap, the number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while absorbing the 125,000 people who enter the labor force each month.

The chart below shows how the job gap has evolved since the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, and how long it will take to close under different assumptions for job growth. The solid line shows the net number of jobs lost since the Great Recession began. The broken lines track how long it will take to close the job gap under alternative assumptions about the rate of job creation going forward.

If the economy adds about 208,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 2000s, then it will take until July 2023—another 12 years—to close the job gap. Given a more optimistic rate of 321,000 jobs per month, which was the average monthly rate for the best year of job creation in the 1990s, the economy will reach pre-recession employment levels by July 2016—not for another five years.

Conclusion

Our economy is still in recovery and the history books will undoubtedly tell the story of the unique challenges facing college graduates in the aftermath of the Great Recession. In 2007, before the recession began, employment for recent college graduates was 4 percentage points higher and average earnings were about $86 per week more. But while the recession may have dampened opportunities for many young Americans, evidence shows that those young Americans with a college degree are better off than their peers without a post-high-school degree.

College enrollment peaked during the Great Recession—a sign that more young people have decided to stay in school to weather the recession. In today’s increasingly global economy, technology and innovation will play an increasingly large role in America’s ability to employ these college graduates and to maintain its leadership in the world marketplace. On June 28th, The Hamilton Project will hold a forum to discuss the next generation of scientific and technological breakthroughs, and the policy and regulatory environment necessary to foster innovation and investment in the United States.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Do Recent College Grads Really Stack Up? Employment and Earnings for Graduates of the Great Recession

June 3, 2011