Americans don’t agree about much these days, but most agree that their democracy is in danger. What most concerns us is not outright failure—after all we had an election in 2020, the votes were counted, the military did not intervene in the election, and the duly-elected winner is in the White House. What prompted the concern about our democracy was the stunningly rapid deterioration in democratic norms that began with Donald Trump’s candidacy, stretched into his presidency, reached a crescendo with his fight to stay in office after the 2020 election, and continues today as he and his supporters sow division, disinformation, and distrust.

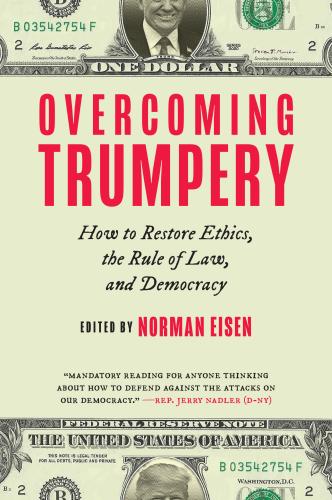

When norms are widely held throughout a society, they can function as robustly as written law. But the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump challenged one norm after another. When that happens in a society, people ask—why isn’t there a law against this? My Brookings colleague, Norm Eisen, has produced an edited volume—called Overcoming Trumpery: How to Restore Ethics, the Rule of Law and Democracy—that answers that question. In it he pulls together thirteen heavyweight legal scholars who tackle a set of issues related to what Eisen calls “Trumpery … a disdain for ethics, the rule of law and the structures and values of democracy itself”.[1] Each of the ten essays in the book provides a valuable road map to action; most of these are legal reforms that would codify or clarify norms that have governed modern American politics and government for at least a half century.

As befits a Brookings publication, the book is a comprehensive roadmap to action. Some of the action items are oldies but goodies—concern about money in politics, fights against voter suppression, unease over lax congressional oversight, and debates over the filibuster, for instance, have been sources of concern about the health of American democracy for some time. In one way or another, all of these vulnerabilities came into sharper focus during the Trump era. But there are other, newer action items in the volume that come as the result of unprecedented behavior by President Trump that broke longstanding norms.

The first two deal with the fact that, unlike all previous presidents, Donald Trump refused to separate his public life from his business life.

To the surprise of many, there is no law requiring presidential candidates to make their tax returns public.

The reason it came as a surprise is that since 1976 all major party nominees for president (with the sole exception of Republican Gerald Ford) have voluntarily released their tax returns.

And yet when Trump refused to make his returns public, first during the campaign and then while in the White House, people realized that this norm was so important that it should be a law. Writing in Eisen’s volume, Virginia Canter makes the case for tax transparency. Although we still don’t have Trump’s tax returns, his legal troubles since then constitute a good argument for why we should see all the tax returns of major party candidates, to enable media and the general public to vet the next potential president.

The second shock to democratic norms came from Trump’s refusal, once in office, to divest himself of his business interests. As his presidency progressed, Trump made millions from visits to his properties by well off Americans and foreigners who came with the expectation that he would be there and hear them out. As Canter points out, “Although the criminal conflict of interest statute, 18 U.S.C sec 208, bars most executive branch employees from participating in any particular matter that would have a direct and predictable effect on their financial interests … there was no statutory basis to hold President Trump accountable for abusing his office by partaking in official decisions that could further his own financial interests.”[2]

Thus, Canter proposes that the emoluments clause of the Constitution be reinforced by legislation which, among other things, bars the president and vice president from being party to any federal contract or deriving benefit from any federal contract and establishes an investigative and enforcement mechanism through agency inspectors generals.

Finally, in recent American history, only Donald Trump was suspected of being under the influence of a hostile foreign power: Russia.

It began with the discovery during the campaign Russians had hacked the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign and Russian agents were engaged in a widespread effort to use social networks to undermine Hillary Clinton and boost Trump. Trump was also surrounded by people, notably Michael Flynn and Paul Manafort, who had close ties to Russia. Once in office, the blatant flouting of norms of behavior in foreign policy, such as throwing notetakers out of the room where discussions with Russians were being held and his lapdog performance in front of Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, fed the theory that somehow Trump was under the influence of a foreign power. The opaqueness of his finances and his refusal to divest only added fuel to the fire.

The third threat to democracy that is the result of Donald Trump, covered in Claire Finkelstein’s essay, involves foreign influence in our democracy. The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) requires Americans lobbying on behalf of foreign governments to register with the Department of Justice. She suggests reforms to FARA that are definitional, set up a civil investigative demand authority, and improve public notice and transparency. And yet, Finkelstein concludes, “even a perfect FARA statute will not do everything that is needed to protect against the insidious effect of foreign efforts to influence the course of democratic governance”.[3]

The final threat to democracy is contained in Trump supporters’ ongoing efforts to undermine America’s traditional election administration. In her essay, Victoria Bassetti points to sham audits and penalizing minor election errors as ways in which Trump supporters in states are seeking to politicize election administration. Two major voting rights bills in the U.S. Congress begin to address these problems but they have both failed. Bassetti points to other more narrowly constructed bills that would outlaw “intimidation and harassment of election officials” and bar interference with election officials as they “tabulate, canvas or certify vote results”.[4]

These four areas of reform work to address the threats to democracy that Trump inflicted on the nation. Had Trump simply receded into the fog of history after his 2020 loss, the calls for legislation in these areas might have gone away. But the threat seems to have metastasized, in large part because of the former president’s and his supporters’ strategic efforts. These are some important ways to stop Trumpery before it does permanent damage to democracy, but the deadline is coming.

[1] Eisen, page 14

[2] Eisen, page 34

[3] Eisen, page 196

[4] Eisen, page 221

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Four ways to save democracy from Trumpery

May 26, 2022