The Mueller hearings provided Congress with two dramatically different narratives. For those who have followed this story day by day, there was nothing new. But for those who have other things to do with their lives, Congress used it as an opportunity to frame the vast amount of information in the Mueller Report and in the indictments and convictions that flowed from his investigation.

Former Special Counsel Robert Mueller sat in front of two separate House committees for more than 6 hours, looking for all the world like a man who wanted to be anywhere else, and gave perhaps the most terse answers ever heard in that august chamber. Yet he really didn’t need to say much. What the members of Congress did, with remarkable discipline, was to delve into the report and use pieces of it to try and tell their story in the hopes that the ultimate sanction on President Trump—impeachment—would either move forward or be left behind.

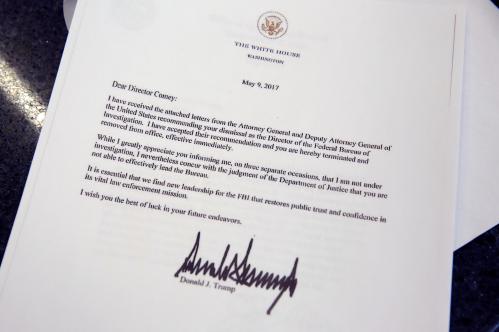

Starting with the Democrats, it was clear that they wanted to focus on obstruction of justice. More than one member of the Judiciary Committee bore down on Trump’s instruction to his White House Counsel to fire Mueller and on his subsequent instructions to create a paper trail showing he never did any such thing. More than one Democrat pointed out that anyone else would have been indicted based upon the fact pattern presented. And Mueller himself acknowledged that while he didn’t believe (because of the Office of Legal Counsel ruling) a sitting president could be indicted, he did say that once no longer president someone could be indicted for obstruction of justice—or any other crime. The Democratic refrain “No one is above the law,” was invoked early and often. With the exception of Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), no one in the House Judiciary Committee talked much about Russian intervention at all.

The emphasis changed somewhat in the afternoon when the scene shifted to the House Intelligence Committee. There, Democrats introduced the notion of greed and hinted in a wide variety of ways that Donald Trump had business interests in Russia—specifically, a desire to build Trump Tower Moscow. Congressman Denny Heck (D-Wash.) called Trump Tower Moscow “a lucrative deal.” He alleged that Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort intended to use his position to make money and he brought up Jared Kushner’s need to raise money for his property at 666 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. “Greed,” he concluded, “corrupts and it’s a terrible foundation for developing American foreign policy.”

If the Democratic refrain was “No one is above the law,” the Republican refrain was “Innocent until proven guilty.” Very few Republicans bothered talking about obstruction of justice, nor did they try to defend the president on those grounds. Instead, they repeatedly painted Trump as the innocent victim of an out-of-control witch hunt. Republican Congressman Tom McClintock (Calif.) asked Mueller the following: “When people associated with Trump lied you threw the book at him? When people associated with Steele lied you did nothing.” And Republican Congressman Jim Jordan (Ohio) asked “Why don’t you charge Joseph Mifsud? The central figure who launches this all—lies to us and you don’t charge him with a crime.” Congressman Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) said, “One of two things might be true: Steele made this whole thing up. Or Russians lied to Steele to undermine our confidence in our newly elected president.”

By the afternoon session, Republicans were intent on trying to sow doubt about the origins of the entire investigation. They returned to the shadowy figure of Joseph Misfud, a spy who may or may not be a Russian agent, who may or may not even be alive. Mueller, if he even knew the answers, could not answer any of those questions because the Russia investigation is part of the shadowy world of intelligence and counterintelligence. There are a lot of redactions in the report, many because of the need to protect sources and methods. And more than one Republican alleged that the Steele dossier was the work of Democratic operatives or an attempt by the Russians at disinformation.

The instant analysis was that nothing much changed. It is doubtful that the pro-impeachment Democrats gained many adherents and it is doubtful that the Republicans convinced many new people of Trump’s innocence. But the longer-term consequences are clear. The Republicans probably did succeed in teeing up doubts about the origins of the investigation—an issue which is now the focus of Justice Department attention. President Trump may avoid impeachment; after all, the clock is ticking and there will soon be an election. But in the long run the Russia investigation has opened up a world of turmoil for him and his business associates—trouble that will come once he is no longer in office and sooner for those not protected by the office of the presidency.

Mueller may be allowed to go into a much-needed retirement but one way or another this story is not over.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of the license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Mueller testimony: Two narratives

July 25, 2019