As we outlined in an earlier article, the 116th Congress is going to look a lot different than its predecessors thanks to a younger, more female, less white new cohort of Democrats. And weeks before even being sworn into office, many new members have already made their presence known—from livestreaming portions of their orientation, to joining an environmental protest in likely-Speaker Pelosi’s office, to exchanging their speakership votes for promises of attention to climate change.

As we outlined in an earlier article, the 116th Congress is going to look a lot different than its predecessors thanks to a younger, more female, less white new cohort of Democrats. And weeks before even being sworn into office, many new members have already made their presence known—from livestreaming portions of their orientation, to joining an environmental protest in likely-Speaker Pelosi’s office, to exchanging their speakership votes for promises of attention to climate change.

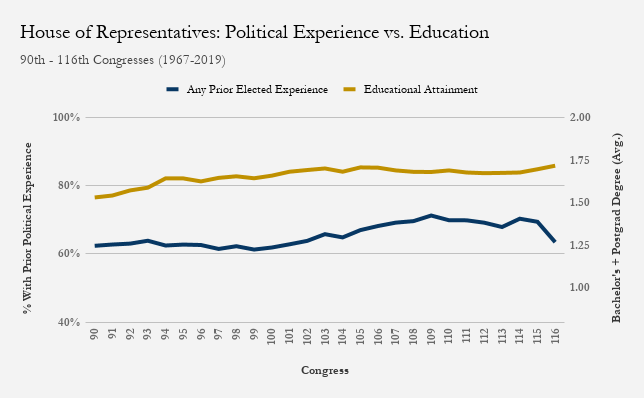

But the incoming freshman class is notable not just because of their demographics, but also because of the types of experience and expertise they’re bringing to Congress. The “Blue Wave” is bringing record levels of educational attainment to the 116th Congress, but it’s also sweeping in the least politically experienced cohort in modern history. These divergent types of expertise, which fit into recent trends in the House, seem likely to have a lasting effect on both the political culture of the chamber and on the types and quality of policy that emerge from it.

We looked at data from 1789 on, but for the following charts we’ll focus on 1967-present.

The highest-educated Congress in history

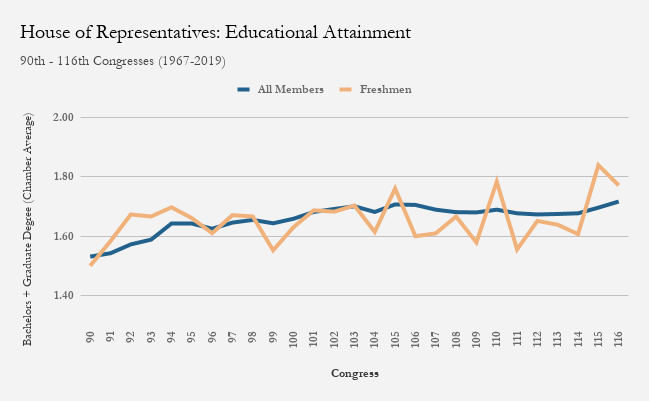

Since the 90th Congress (1967-1968), members of Congress have continued to become better educated. The House of Representatives has long maintained a very high proportion of college graduates for decades with a minimum of 94 percent of members earning a bachelor’s degree during the period. But the chamber has decidedly increased its share of lawmakers who have earned postgraduate degrees, including law, medical, and master’s degrees. In the 90th Congress, less than 60 percent of representatives had completed postgraduate education. The 116th Congress will boast the most educated Congress in history with 72 percent of the House having earned a graduate degree.

Freshmen have often outpaced the education levels of the rest of the chamber, particularly in the most recent congresses. The incoming freshmen of the 116th are the among the highest-educated incoming class ever, second only to their predecessors in the 115th Congress.

Educated but very inexperienced at governing

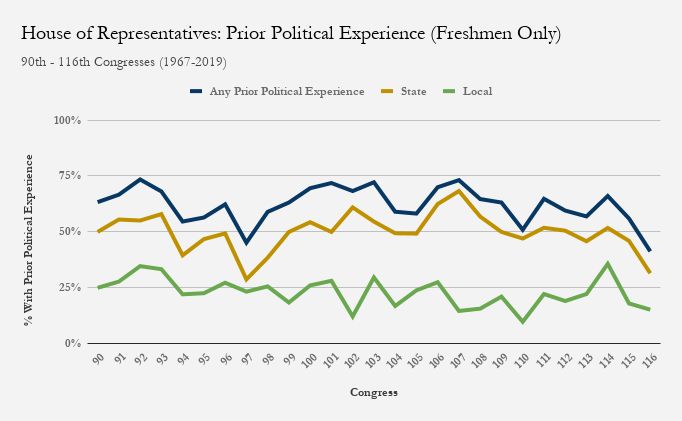

This new class is record setting in another way: the House’s incoming freshmen are the least politically experienced cohort in the chamber’s history. Seriously, we looked. Eighty-six percent of the very first Congress, in which all members were technically freshmen, had previously held elected office. The second-least politically experienced freshman class (45 percent of members holding prior elected office) belongs to the 97th Congress (1981-1982).

In the last two congresses, and in the upcoming 116th Congress in particular, the political experience of freshmen members has taken a nosedive. Of the new members of the 114th Congress, for example, 52 percent had state-level political experience (such as serving as a state legislator or state attorney general), and 36 percent had local experience (such as serving as a mayor or on a city council). For the 116th Congress freshmen, those numbers are 32 percent and 15 percent respectively. Only 41 percent of freshmen had any prior political experience of any kind. That makes it the least-experienced freshmen class in the history of the House.

Receding institutional memory in the chamber

Receding institutional memory in the chamber

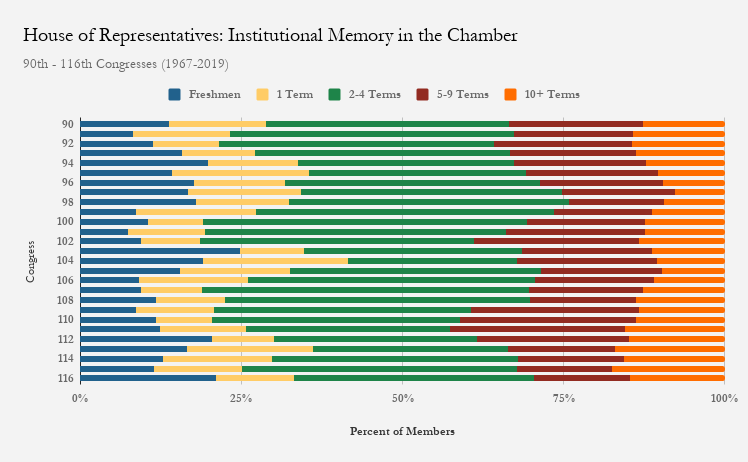

In a period of extreme dissatisfaction with Congress and with questions increasing about its own capacity to do its job, many point to a decreasing level of institutional memory as a main culprit for why Congress seems unwilling and unable to perform its expected duties. After all, the inevitable result of any wave election is that a large portion of the House is completely new to the job. As a result, a non-trivial portion of the chamber is unfamiliar with the intricacies and traditions of Capitol Hill and is increasingly removed from more functional, productive eras in the House. Instead, members only know hyper-partisan gridlock.

As the above graphic makes clear, however, levels of institutional memory—here measured as number of terms served—have ebbed and flowed since the late 1960s with freshman and sophomore members regularly constituting up over one quarter of the chamber. The 116th Congress will skew more inexperienced with exactly one-third of lawmakers having served one term or less upon being sworn in come January. For comparison, the Gingrich Revolution’s 104th Congress was made up of 38 percent freshmen and sophomores.

But important to note, it isn’t the well-experienced members who are booted from the chamber when large freshman classes are elected. The proportion of members serving at least 10 years in the House has only dipped below 25 percent once since the late 1960s (98th Congress), providing a strong counterweight of experience to the inexperienced wing of the chamber. And the share of “lifer” members (those serving 20 or more years) has remained remarkably consistent over the period, at around 15 percent; in fact, its share has slightly increased in recent years.

Instead, it is the moderately experienced members—those serving four to eight years—whose congressional tenures are most likely to end, either through defeat or retirement. This dynamic gives us a few great insights into common frustrations on Capitol Hill.

First, many of the moderately experienced members take themselves out of the chamber by declining to run for reelection. Of course, many of these members face daunting reelection prospects, but as has been well-documented, these members, after having become intimately familiar with congressional dysfunction after a few terms of service, decry their limited involvement, the centralized, leadership-driven lawmaking process, and constant fundraising demands. Freshmen and sophomores are hopeful about their impact, but after a few terms lawmakers become frustrated to the point of retirement.

And second, successful wave elections often characterize the institution as badly in need of new energy, ideas, and processes. Young members are elected on promises of action in an environment mired in gridlock. They promise to return the House to the people through the upending of the centralized policymaking process. The 2018 election was no different, and so far, this incoming freshman class has proven willing to take on the established ways and leaders of the Hill. How long the effects of the 2018 blue wave lasts are still to be determined.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Congress in 2019: The 2nd most educated and least politically experienced House freshman class

December 28, 2018