Few federal government problems got fixed in 2013. The process for nominating and confirming federal judges was no exception. Headlines were dominated by an ideological fight over nominees to the court of appeals for the District of Columbia circuit—masquerading as a fight over whether the court needed three of its eleven judgeships. Partly in response to Republicans’ filibustering President Obama’s nominees to those disputed judgeships, Democrats changed Senate rules to deny the minority the right to block most confirmations.

In the background was a continued breakdown of the once-almost ministerial process of presidential nomination and senatorial confirmation to fill judicial vacancies. The year saw:

– Nominations submitted at a slightly faster pace than in the Clinton, and a much faster pace than the Bush, administrations;

– Vacancies at year’s end greater than at the start of the year and the start of the administration;

– Nominee-less vacancies highly concentrated in states with at least one Republican senator;

– Five-year rates of appellate confirmations that were almost the same as those of the Bush and Clinton administrations, but district confirmation rates well below the Bush administration’s and slightly lower than Clinton’s;

– Contentiousness over district nominations growing similar to long-standing contentiousness over circuit nominations;

– A party-of-appointing president division on the courts of appeal slightly favoring Democratic appointees, reversing a slight Republican-appointee advantage at the start of the year.

2013 saw some preposterous claims (Senator McConnell’s “a confirmation rate of 99 percent”)—and cherry-picked claims (President Obama’s “my judicial nominees have waited three times longer to receive confirmation votes than those of my Republican predecessor”).

My goal in this brief year-end wrap-up is to put these developments into perspective, citing a few salient figures drawn from tabulations at the end of the piece.

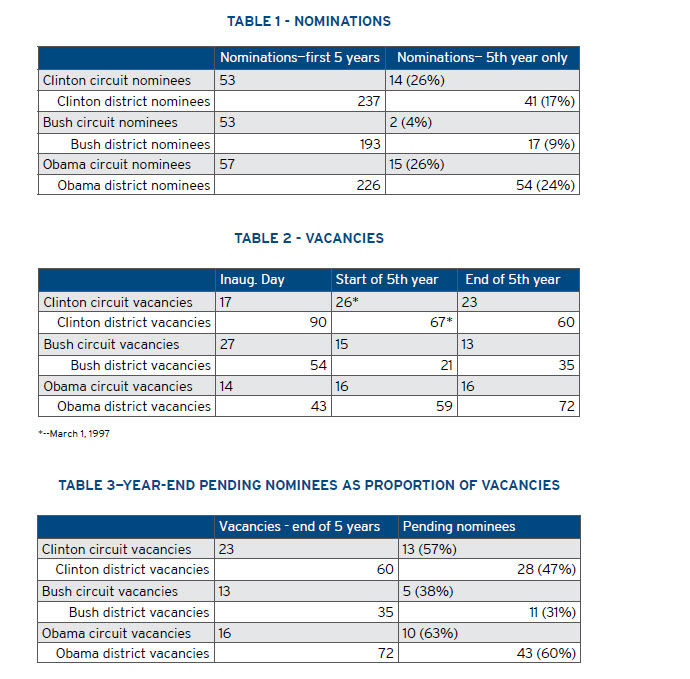

Nominations By the end of its fifth year, Obama had a nomination pace similar to Clinton’s. (Table 1) About a quarter of judicial nominations came in 2013. The press marveled that “Obama, after an extraordinarily slow start, has moved way ahead of Bush II on nominations.” That is true, however, only because President Bush made a mere handful of nominations during his fifth year. (He submitted few circuit nominations, battling instead to get long-standing nominees confirmed. There were few district nominations because he had been highly successful in filling vacancies in his first four years.)

Vacancies and nominee-less vacancies Despite the uptick in nominations, Obama faces more judicial vacancies than in 2009 or January 2013. Bush and Clinton, by contrast, saw the number of vacancies decline overall by the end of their fifth years in office. (Table 2)

Obama has come in for criticism, not only for a high vacancy rate, but also for nominee-less vacancies. In April, Senator Charles Grassley (R-Ia,) invoked the groundless claim of a 99 percent confirmation rate and then went on to push “the White House [to] get down to work, decide who they’re going to nominate, and get the nominations up here. Presently . . . 3 of 4 vacancies have no nominees . . .”. That was true in April, but by the end of 2013, Obama had higher proportions of pending nominees to vacancies than did Clinton at the end of 1997 and much higher proportions than did Bush at the end of 2005. (Table 3)

Eliminating nominee-less vacancies, though, is more complicated than the White House’s simply “get[ting] down to work.” Senate Judiciary Committee chair Patrick Leahy rigorously honors a committee tradition of not processing nominees who are opposed by either home-state senator, regardless of party. They indicate their opposition by not returning the “blue slip” that Leahy sends home-state senators asking them to check “I approve” or “I oppose” on each nominee.

It is thus pointless for the administration to send the Senate a nominee without those senators’ assurances they will not block the nomination. Once, other-party senators rarely objected to administration judicial nominees. They acknowledged that elections have consequences and litigants need judges in order to use the courts, and they realized that eventually their party would control the White House and expect deference from other-party senators. In some states, those notions seem today as relics of a hoary past.

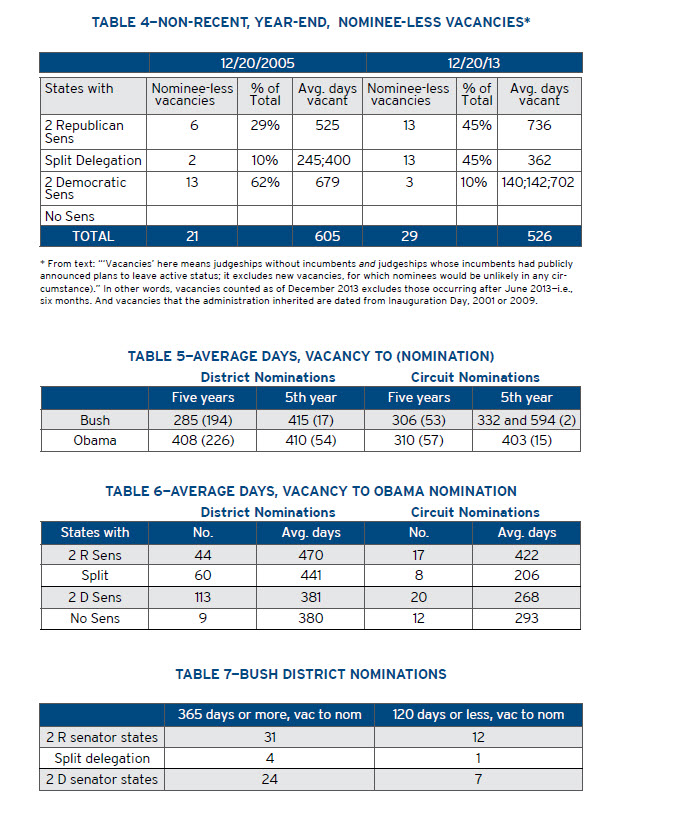

Today, some home-state senators, mostly Republicans it appears, are either insisting on nominees that the administration cannot support or refusing to accept nominees preferred by the administration, or perhaps slow-walking the process, enforcing their March 2009 warning that “if we are not consulted on, and approve of, a nominee from our states, the Republican Conference will be unable to support moving forward on that nominee. . . .”. The results of what one Republican senator called “many months of serious negotiations with the White House on the importance of filling . . . vacancies” became apparent in 2013. Of the 29 nominee-less vacancies, 26 were in states with a Republican senator and were well over a year old on average. Only three were in states with two Democratic senators; two of those three vacancies are comparatively recent. (“Vacancies” here means judgeships without incumbents and judgeships whose incumbents had publicly announced plans to leave active status; it excludes new vacancies, for which nominees would be unlikely in any circumstance). (Table 4) Some long-standing vacancies in Georgia got nominees last week but they produced howls of protest from Georgia Democrats, as noted later.

Texas has almost 30 percent of the nominee-less vacancies—one dating from 2008, another from 2010, two from 2011, three from 2012, and one from 2013. Five of them meet the Judicial Conference’s definition of a “judicial emergency,” based on the vacancy’s length and the court’s workload. Two, both from 2011, are in a district with the third highest weighted caseload in the country, and the district with the 2008 vacancy has the ninth highest weighted caseload. (Split delegation state Pennsylvania has five of the nominee less vacancies, and Florida four.)

At this point in the Bush administration, nominee-less vacancies were concentrated in states with Democratic senators, although not quite as intensely as today’s Republican senator concentration (72 percent versus today’s 90 percent). Fifteen of the 21 nominee-less vacancies were in states with Democratic senators, and vacancies in two-Democratic senator states averaged 679 days. (Table 4) All five California were “judicial emergencies,” at an average age of 682 days.

Time—vacancy to nomination Overall, time from district vacancy to nomination increased substantially from Bush to Obama—from 285 days to 408 while time to circuit nominations were essentially the same. Obama’s district nominations came slightly faster in states with two Democratic senators—381 days on average for district nominees compared to 470 days in two-Republican senator states). But the numbers did not always play out as one might expect: mixed-delegation states got circuit nominees faster than either. (Tables 5 and 6)

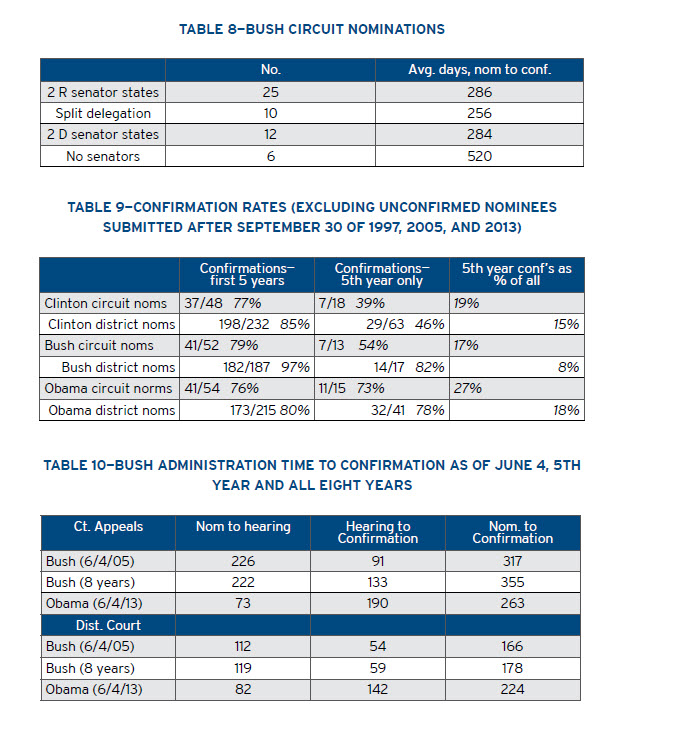

I did not have time to conduct a complete analysis of Bush district nominees’ time from vacancy to nomination times, but information on those that took over a year from the vacancy and those that took less than 120 days shows slightly more nominations in states with two Republican senators in both categories. (Table 7) The differences in vacancy-to-nomination time for all 53 of his circuit nominees were similarly modest. (Table 8) The time it takes to get nominees to the Senate depends, of course, on much more than home-state senator resistance or cooperation. There have been fairly steady anecdotal reports, for example, of the Obama administration’s jousting with senators of both parties over proposed nominees in terms of racial and gender factors.

Confirmations Obama’s five year success rate in getting circuit nominees confirmed—76 percent—is almost the same as Bush’s and Clinton’s, although without the two post-filibuster change confirmations, that rate would be 72 percent. His 80 percent success rate for district nominees, though, is substantially below Bush’s 97 percent rate. For 2013 only, his circuit confirmation rate of 73 percent is better than Bush’s in 2005, but Obama had slightly more trouble in 2013 in getting district confirmations than did Bush in 2005. (Table 9)

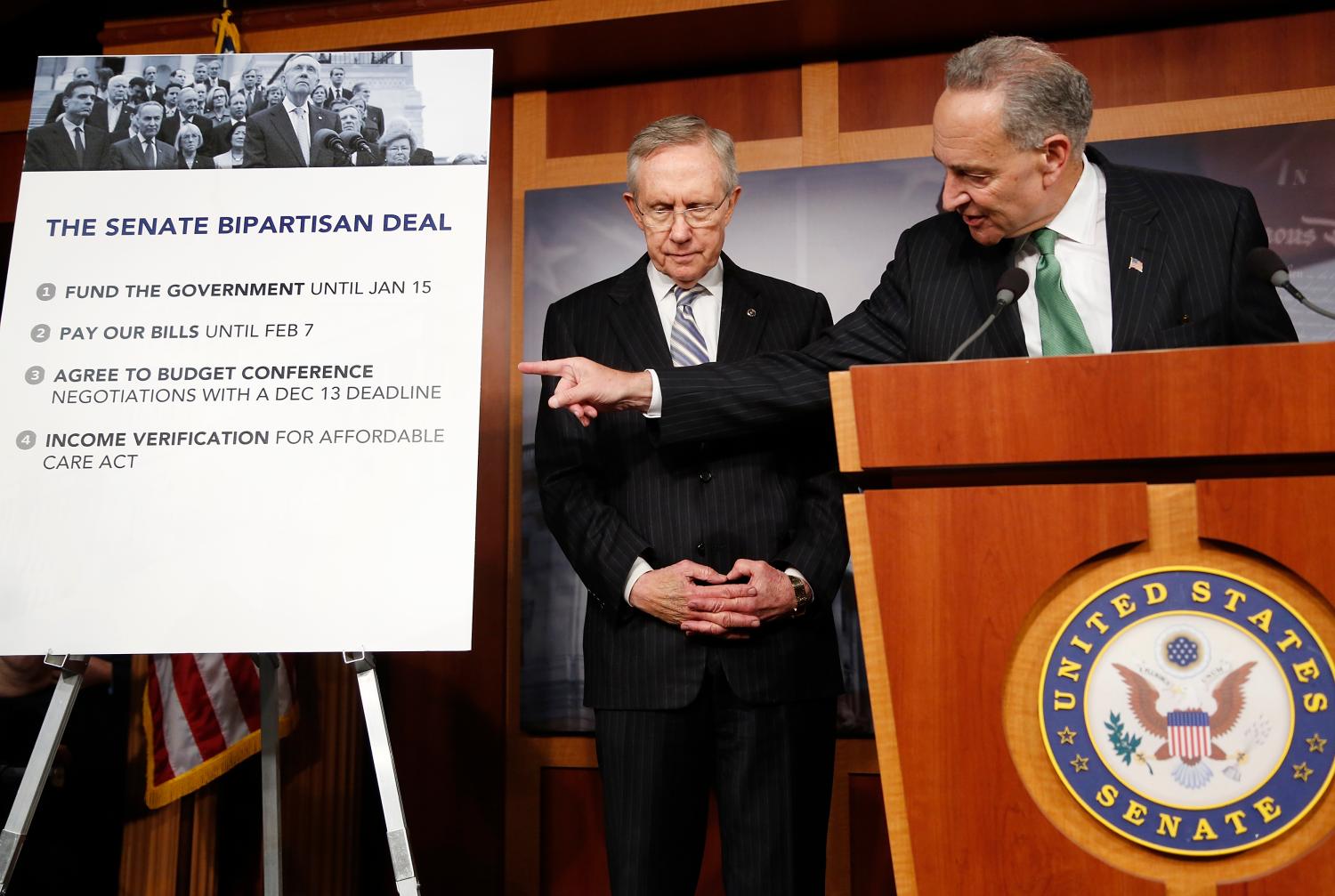

Republican claims that the Senate confirmed 99 percent of Obama’s nominees became a battle cry in 2013 after Senate Democrats changed the filibuster rules. A 99 percent confirmation rate, if true, would have removed any justification for abolishing the filibuster and would have justified casting that move as an oversized response to the fall filibustering of nominees to the DC circuit, which Republicans argued didn’t need the judges anyway. In fact, though, the Senate confirmed nothing close to 99 percent of Obama judicial nominees. And whether the D.C. circuit, which stood at four Republican and four Democratic appointees at mid-year, needs all of its eleven judgeships is not a closed question but one meriting further, non-partisan analysis.

The filibuster fight could have been avoided had the Senate been allowed to confirm Obama’s three most recent nominees to that court and had it requested the Judicial Conference to undertake an empirically based comparative analysis of court of appeals workload, the results of which could bear on whether to fill the vacancies that will occur when the D.C. circuit’s three active judges who are now or soon will be age 70 or older take senior status.

Confirmation contentiousness Contentiousness in the circuit confirmation process has characterized circuit nominees for the three most recent administrations. Obama’s claim, however, when introducing his three most recent nominees to the DC Circuit on June 4, 2013, (“my judicial nominees have waited three times longer to receive confirmation votes than those of my Republican predecessor”) was at best misleading. It may have been true if circuit and district confirmations are lumped together and measured solely from when the Judiciary Committee reported out the nominees to the floor votes. Such quantitative contortions, though, are not meaningful.

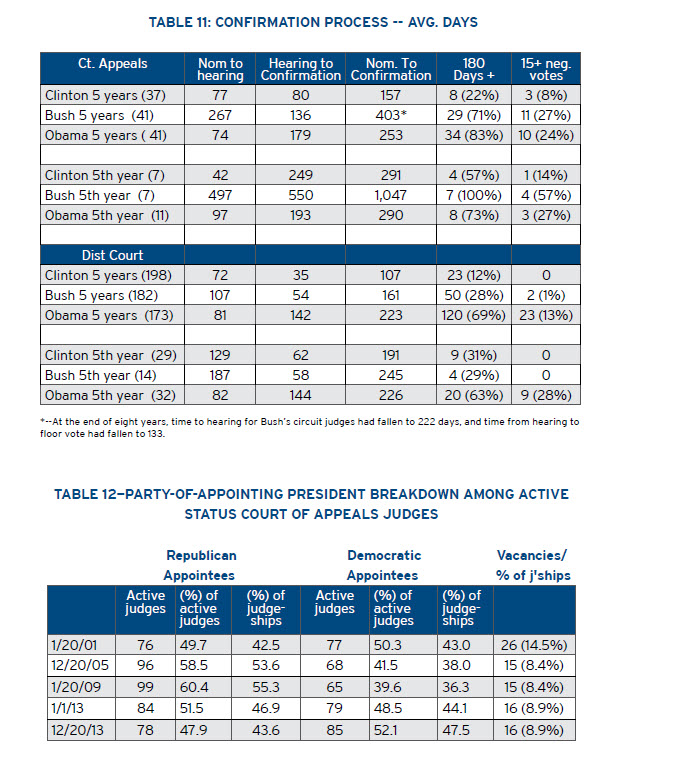

Obama’s statement was certainly not true as to circuit judges alone, from nomination to confirmation. (Table 10) And focusing on district judge time to confirmation in the first five years, 12 percent of Clinton’s district judges waited over 180 days for confirmation, a figure that rose to 28 percent under Bush and is now at 69 percent for Obama. Bush’s district judges waited longer to get hearings, but once they got them, they went to confirmation fairly quickly. Just the opposite was true for Obama. (Table 11)

Comparing processing times for Bush and Obama circuit judges is not profitable at the end of five years because, in 2005, following the 2005 Senate agreement to process most Bush circuit nominees, the Senate confirmed some nominees whom Bush first submitted in 2001 or 2003, producing much higher wait times than for all eight years of the Bush administration (as Table 11’s star note explains).

The amount of time nominees wait for a confirmation vote is important for nominees, especially those in private practice, who sit in a state of suspended animation while they wait. The steady increase in the amount of time district nominees wait for confirmation—60 days on average for President Reagan’s eight years, 135 in Clinton’s, 178 in Bush’s, and 223 so far in the Obama administration—no doubt discourages some potential candidates from undergoing the process. The prospect of a drawn out confirmation process—and declining confirmation rates— help explain why the proportion of district judges who came from the private practice of law has decreased from about two thirds during the Eisenhower administration to one third now, and the proportion of former state and term-limited federal judges has increased. Whether that is a good or bad thing for the judiciary is an open question, but it’s clear that this change is occurring. And it’s occurring alongside another index of contentiousness: district candidates who got more than 15 negative confirmation votes rose from none under Clinton, to one percent under Bush, and 13 under Obama.

Changing Composition of Court of Appeals Obama, in terms of the party of the president who appointed circuit judges in active status, has not able to put as much of an imprint on the courts of appeals as did Bush by the end of his fifth year. Obama had a circuit confirmation rate about the same as Bush’s, but Bush inherited an appellate judiciary split evenly between Republican and Democratic appointees, with 26 vacancies. He was able by the end of 2005 to shift that split to 59 percent Republican appoints (and 60 percent by the end of eight years). Obama inherited that 60-40 split. At the end of 2013 it slightly tilted to Democratic appointees (52% to 48%). (Table 12) In 2009, seven courts of appeals had a majority of Republican appointees among their active status judges. Today, seven of them have Democratic-appointee majorities.

These figures, though, are somewhat less than meets the eye. Party-of-appointing president is hardly a sure-fire predictor of judicial decisions, and randomly selected three judge panels often include visiting judges and senior judges, a fact brought home in the debate over the so-called four-four party-of-appointing-president balance among the D.C. circuit’s active judges.

2014 is uncharted territory. Confirmation rates will no doubt increase, now that the Senate has removed the threat of filibusters. But because Republican senators no longer have the ability to block majority confirmation votes, they may use their veto power over potential nominees even more vigorously. Senator Leahy has said that [a]s long as the blue-slip process is not being abused by home-state senators, then I see no reason to change that tradition.” 2014 may test that assumption. The late December call from Representative John Lewis (D-Ga.) and other civil rights leaders for Obama to withdraw a bloc of Georgia nominees he had submitted a week earlier may gain traction as an indictment of the power over nominations exercised by home-state senators who have very different views of judicial qualifications than many in the Democratic party. Or the administration might counter senatorial use of pre-nomination vetoes, as Michael Shenkman has suggested (summarized here), by posting “the status of pre-nomination negotiations, although not the names of the [potential] nominees themselves” as a means of shedding light on the sources of delay in getting nominees before the Senate.

Republicans also may make more use of the procedural options still open, such as refusing to attend Judiciary Committee hearings or business meetings, preventing quorums from sending nominees to the floor for votes. They may continue to insist on rigorous enforcement of rules allowing, after majority votes to cut off debate, two hours of debate for district court nominees and thirty for circuit nominees.

And, although it is naïve, perhaps (as I proposed at the first of the year), the process is now so broken than both parties might see it in their self-interest to consider a three-branch, truly bi-partisan commission to suggest fixes that the president and senate in place in 2017 might consider.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Judicial Nominations and Confirmations: Fact and Fiction

December 30, 2013