When stressed-out students and teachers return to their schools, it will be a challenge not only to re-engage with education, but to do so in an environment where truth itself has come under challenge. One recent report from the RAND Corporation, based on a national survey of elementary and secondary students and teachers, finds that even before the pandemic, the war over “truth” and decline in civility in society at large had seeped into classrooms.

Laura Hamilton, Julia Kaufman, and Lynn Hu—the authors of the RAND study, appropriately titled “Preparing Children and Youth for Civic Life in the Era of Truth Decay”—report that, while there was broad support among teachers to address this challenge through enhanced civic education, most social studies teachers felt ill-equipped to do it.

A revival of civics instruction in middle and high school can help. But we shouldn’t stop there. By teaching debate techniques, we could enhance civility, improve student engagement and learning, and, in turn, narrow racial and ethnic disparities in educational outcomes. Governments at all levels and education leaders can help catalyze this educational revolution.

The Virtues of Debate-Centered Instruction

As I outlined in my recent book, “Resolved,” the pedagogical technique I have in mind is “debate-centered instruction” (DCI), which is modeled after competitive debate. In competitive debates, the student participants offer reasoned positions—backed by evidence—in civil discussion, without name-calling and constant interruptions. In other words, the kind of discourse that should be the basis of all functioning democracies.

Two academic studies, one of urban schools in Chicago and the other in Baltimore, confirm what my own experience and common sense suggests: that competitive debate improves students’ academic performance, especially for students of color and girls. They each use proxy variables that attempt to control for self-selection, or the propensity of higher-performing students to engage in debate.

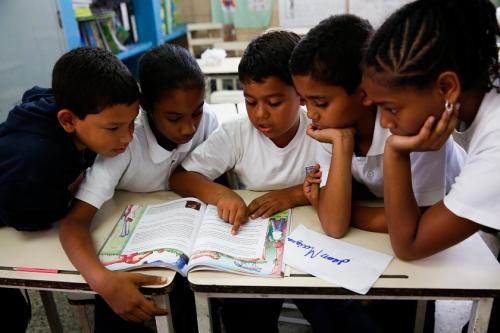

However, less than 1% of high school students—and even less for those in middle school—participate in extracurricular competitive debate tournaments. DCI is delivered in classes by posing a claim (such as, “The protagonist in the novel is a universal tragic figure,” or “The U.S. should not have entered World War I.”), then asking student groups to find evidence for and against that claim and the reason why that evidence supports each position. All arguments are presented orally, which develops students’ speaking skills (they’re much more likely to talk with and to their peers than in front of an entire class, at least initially), and ultimately improves their writing and reasoning abilities.

My book profiles two entrepreneurs promoting DCI, Les Lynn and Mike Wasserman (both former highly successful debaters), and the teachers they are leading. Since publication, I have learned about many other teachers doing similar things on their own. One outstanding example is AnnMarie Baines, a 20-year veteran debate coach and former high school debater. She founded The Practice Space, a nonprofit in California that champions the practice of valuing and developing voices of all ages through programs, coaching, and curriculum.

What is the impact of DCI? Lynn and Wasserman have been surveying their teachers and analyzing student performance in schools with largely nonwhite student populations for over five years. They report substantial gains in students’ standardized test scores, grades, and attendance, among other outcomes, following the introduction of DCI teaching techniques. Teachers and principals who have used or overseen the use of DCI also are overwhelmingly enthusiastic about it. As the former principal of Proviso West High School Chicago, Dr. Nia Abdullah, told me, the teachers in her school embraced DCI, finding it helpful in reducing student boredom by actively engaging students in teaching themselves and their peers.

DCI is not just for secondary education. Chris Medina, former debate coach at Wiley College—the HBCU famous for winning the 1935 national college debate championship that was featured in the movie “The Great Debaters¸” and which has continued producing college debate champions—documents in his Ph.D. dissertation unusually large and statistically significant gains in the reasoning ability of Wiley students taught through DCI techniques. Medina is now the executive director of the HBCU Speech and Debate Association.

With students returning to in-person learning, DCI is an ideal way to re-engage them in the joy of learning while instilling in them a “learning mindset” that will be benefit them in school and beyond. Instilling a love-of-learning mindset through DCI could help to narrow the gaps in educational attainment across socioeconomic groups that have widened during this crazy year of remote and hybrid learning. Likewise, DCI offers one way to begin to narrow the deep partisan and ideological divisions in our country and to restore the civility in discourse.

A Way Forward

All these benefits can only be realized over time, but it is certainly time to start trying, beginning with students—our future voters. What better way to begin healing than by teaching students how to engage in civil discourse, and to do so constructively?

Governments at all levels and education leaders can promote greater use of DCI in the classroom. At the district level, superintendents (with or without the encouragement of local school boards) can encourage teachers, directly or through their schools, to take professional development (PD) instruction from experienced DCI instructors, using a limited portion of existing PD budgets. Likewise, state education departments can encourage school districts to take this step. And the Department of Education, through matching grants to states or to school districts directly, can incentivize these PD initiatives throughout the country.

There are several DCI training models to choose from, all of which use some type of initial teacher training during the summer before the school year begins, and then some type of mentoring or coaching of the teacher participants during the school year: full-time in-school DCI mentors, as is the case now in Boston and Chicago; or instruction and mentorship delivered remotely, a recent initiative for teachers nationwide spearheaded by New York high school teachers/debate coaches Steve Fitzpatrick and Radley Glasser, organized by Christi Griffin of The Ethics Project, and just funded by the Kauffman Foundation (and with which I am personally involved).

Fortunately, there are multiple educational innovators out there experienced in using DCI techniques in the classroom to help disseminate an instructional technique they know that works. It does so on multiple levels–improving educational achievement, narrowing achievement disparities, and imparting civility in today’s students and tomorrow’s voters. We could use progress on any one, ideally on all three, of these fronts right now.

The author would like to thank each of education pioneers discussed in this essay and Dr. Anna Rosefsky Saavedra, a research scientist with the University of Southern California’s Dornsife Research Center, for their continuing advice and suggestions on earlier drafts. The author has also been providing assistance to each of the organizations featured here on scaling their DCI activities, but has no financial interest in any of these endeavors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).