The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted schooling nationwide, raising serious concerns about the impact of the pandemic on children’s learning, the ways online learning may be exacerbating racial inequities, and the need to balance the strong desire for in-person learning with the risks posed by the pandemic. To date, these debates have centered around the experiences of children still enrolled in public schools, either remotely or in-person. Relatively less has been written about the experiences of the “missing children”—those who have not enrolled in public school at all.

Public school enrollment has dropped nationwide, with the sharpest declines evident in the earliest grades: prekindergarten and kindergarten. A recent NPR poll of 60 districts in 20 states showed an average kindergarten enrollment drop of 16%. Another analysis, this one from 33 states, showed that roughly 30% of all K-12 enrollment declines were attributable to kindergarten. Although there has been less systematic reporting on prekindergarten enrollment, local accounts suggest striking declines.

These early-grade enrollment drops are troubling given the importance of early learning experiences for children’s school readiness. High-quality experiences in the early grades have also been linked to reductions in special education placements and grade retention, and increases in high school graduation rates and adult wages.

Further, enrollment declines could exacerbate already large socio-economic and race-based achievement gaps at school entry. However, there has been little data about these missing children to date, so the equity implications have been unclear.

New data from Virginia shows divergent enrollment patterns by economic status and race

As part of our partnership with the Division of School Readiness at the Virginia Department of Education, we examined how enrollment in prekindergarten and kindergarten changed between the fall of 2019 (pre-pandemic) and the fall of 2020 (mid-pandemic), as well as whether these patterns varied by students’ socio-economic status and race. As a point of comparison, we also looked at enrollment patterns for first through fifth grade.

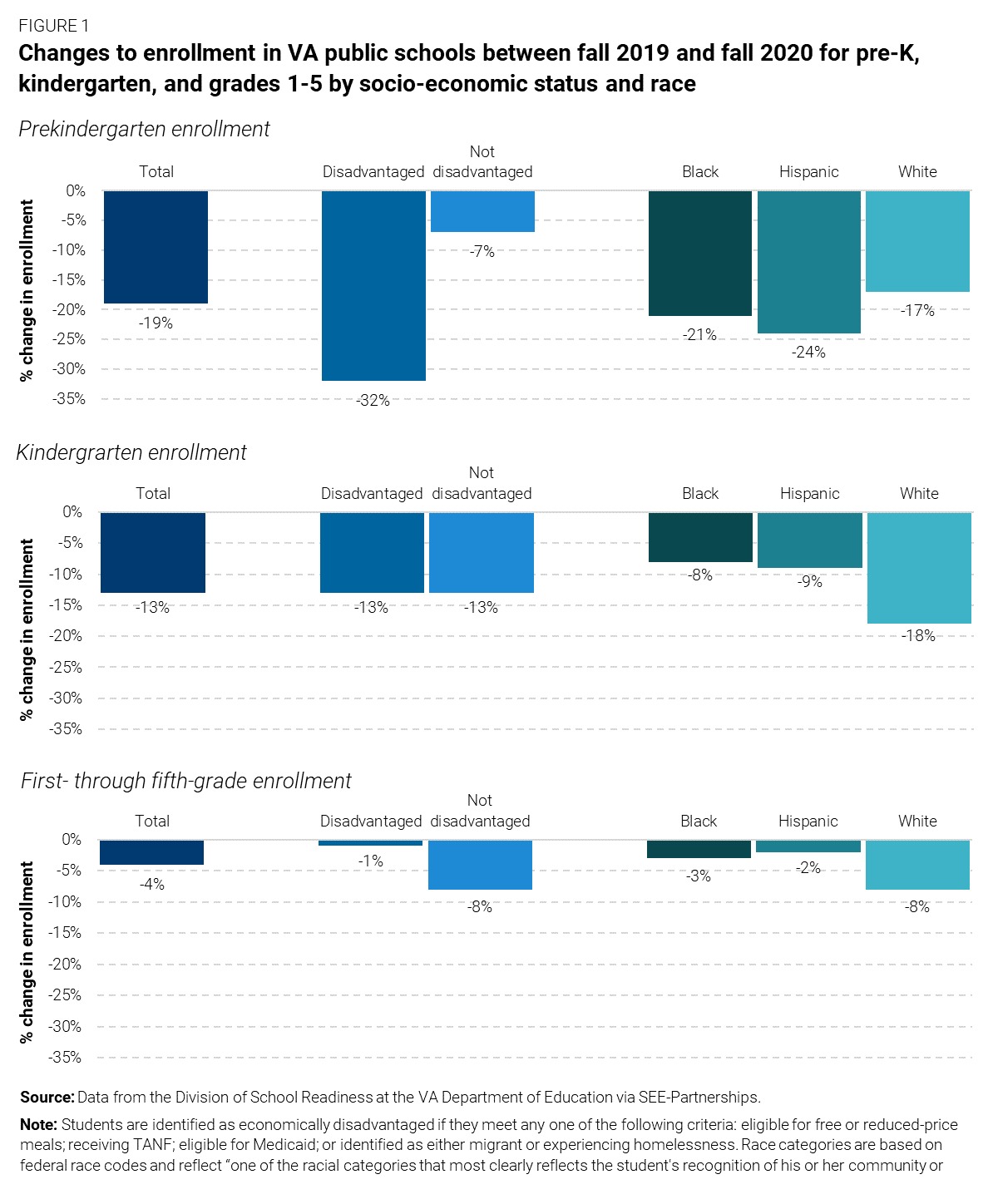

Similar to findings from other states, we found very large drops in public school prekindergarten enrollment (20%) and kindergarten enrollment (13%). In grades one through five, drops were much smaller (4%-5.5%, as shown in Figure 1). However, these declines mask considerable variability by race and socio-economic status, as measured by the state’s “economic disadvantage” indicator.

Prekindergarten drops were most pronounced for students who are economically disadvantaged, Black, or Hispanic. In fact, enrollment among children considered economically disadvantaged dropped by 32%—more than four times as large as the rate observed for non-economically disadvantaged children (7%, as seen in Figure 1, Panel 1).

Among kindergarteners, we found no differences in enrollment declines by socio-economic status—both groups fell by 13%—and the largest drops were among white families (as seen in Figure 1, Panel 2).

Interestingly, the patterns for grades one through five were the reverse of those observed for prekindergarten. Enrollment declines were concentrated among non-economically disadvantaged children (8%). They were about twice as large for white children (8%) compared to Black (3%) and Hispanic (4%) children.

The experiences of children not enrolled in public schools

The implications of these enrollment drops will depend on the types of learning experiences that children had in the absence of public schooling. Media accounts suggest increases in private school enrollment, particularly among high-income families looking for in-person alternatives to remote public schools. These private school switches may explain the patterns observed among non-disadvantaged families in grades one through five.

Because prekindergarten is not required in Virginia, and families have the option to delay kindergarten entry, the calculus may have been different for parents of younger children. Some enrolled their children in private schools or child-care centers that offered in-person or full-day options. Others opted out or delayed school altogether, instead relying on parents, family members, or other adults for child care.

One factor that may have been particularly salient for parents of young children is whether or not their public school offered in-person learning opportunities. Online learning has proven particularly challenging or impractical for very young children. Many parents have expressed concerns about online learning, including worries about young children’s attention spans, the impact of prolonged screen time, and the need for constant adult supervision. Indeed, as shown in Figure 2, prekindergarten and kindergarten enrollment declines were almost twice as large in districts with fully remote instruction—which enroll nearly 80% of all children in these grades. We do not observe this pattern in the older grades.

While we do not yet have a clear understanding of these alternate experiences, the Virginia data make clear that many economically disadvantaged children who would have otherwise enrolled in public school prekindergarten and kindergarten did not enroll this year.

The implications of COVID-19-era enrollment drops in the early grades may be extensive and long lasting

These drops raise serious concerns for children’s early learning. Already in fall 2020, Virginia saw large increases relative to 2019 in the percentage of incoming kindergartners at a high risk for reading failure based on literacy assessments. Researchers predicted that these spikes will result in a 25% increase in the number of children failing to reach proficiency on third-grade reading assessments.

Nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns about children’s learning are worsening. Young children who are not in school may be missing out on screenings for much-needed developmental supports or evaluations for special education services. They are losing opportunities to build the relationships with peers and teachers that make the early grades so critical.

Some families may have found ways to counteract these missed opportunities at home, but many are experiencing high levels of stress during the pandemic and are struggling to balance work and family responsibilities. Low-income families in particular are struggling profoundly with issues like food insecurity, unemployment, and mental-health challenges that make it extremely difficult to support children’s learning needs.

As vaccines roll out, controlling COVID-19 infections and getting young children back into school is a top priority by the new administration. When schools do reopen, they will need to find novel ways to meet the diverse needs of children who had wide-ranging experiences during the pandemic and who come to school with varied skills.

Doing so will be a long-term and labor-intensive prerogative. For the time being, states and districts should consider offering publicly funded summer schools and camps to get the youngest children—particularly the “missing” ones—back into classrooms learning and interacting with their peers as soon as possible. When possible, this should be done in collaboration with child-care providers to create full-day coverage and support take-up among working families.

Beyond this, schools will need considerable resources, time, and flexibility to assess the wide-ranging developmental needs of children and to target a host of needed supports. They will need to think creatively about how best to structure classrooms and learning experiences to meet the very divergent needs of children in the early grades—especially those youngest, most vulnerable learners who missed out on learning opportunities at a uniquely critical moment in their development.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).