Substitute teachers are an important (yet oft-ignored) group of educators in the U.S. school system. The reason is simple: Substitute teachers spend substantial time with K-12 students. Like other professionals, teachers are absent from work for various reasons, such as sickness, professional development, or personal issues. Based on one estimate drawn from a sample of large U.S. metropolitan districts, teachers miss an average of about 11 days out of a 186-day school year. This means that students spend, on average, approximately two-thirds of a school year with substitute teachers during the entirety of their K-12 schooling—not a trivial amount of time.

Teacher absences are not only common, but also detrimental to student learning. Based on one study, 10 additional teacher absences lead to 1.2% and 0.6% of a standard deviation decrease in math and English Language Arts test scores, respectively. Several other research papers using data from multiple contexts reached similar findings. Higher-quality substitute teachers may be able to mitigate some of the negative impacts of teacher absences. Indeed, one study shows that certified substitute teachers are more effective than their uncertified peers.

However, many school districts nationwide had already been facing severe shortages of substitute teachers before the COVID-19 pandemic, and early evidence suggests the pandemic has exacerbated staffing problems. The Madison district in Ohio, for example, reported having less than a third of the substitute teachers needed to cover classes. In Michigan, districts were using billboards to attract potential substitute teachers, given shortages that were prevalent across the state. The inability to find a substitute teacher might not seem problematic initially, as another teacher or administrator with spare time can often cover a classroom when a substitute teacher is not available. Yet repeated occurrences can quickly become burdensome for staff who are frequently called upon to cover a peer’s classroom.

In a recent paper published in Education Finance and Policy, my co-authors, Susanna Loeb and Ying Shi, and I set out to provide the first systematic description of the prevalence of the substitute teacher shortage, how it varies across schools, and how various factors drive the distribution we see. We used detailed administrative data covering school years 2011-12 to 2017-18 from a large urban school district on the West Coast to evaluate the extent to which schools might have difficulty sustaining a substitute teacher workforce. We also administered surveys to both regular teachers and substitute teachers in school year 2017-18 to gauge their perceptions of substitute teaching.

On average, teachers in the sample district were absent for about 11.8 days, or 6.6% of the time, which is commensurate with previous research. Of the 11.8 teacher absences per year, an average of 10.9 days were covered by a substitute teacher. When an absence was not covered by a substitute, students were split up into other classrooms with permanent teachers about 37% of the time; a teacher with a prep period covered the class 35% of the time; a school administrator covered the class about 12% of the time; and other forms of coverage took place for the remaining 16% of the time. A teacher’s non-covered absences can affect their colleagues and students across the school, not just those in the absent teacher’s classroom.

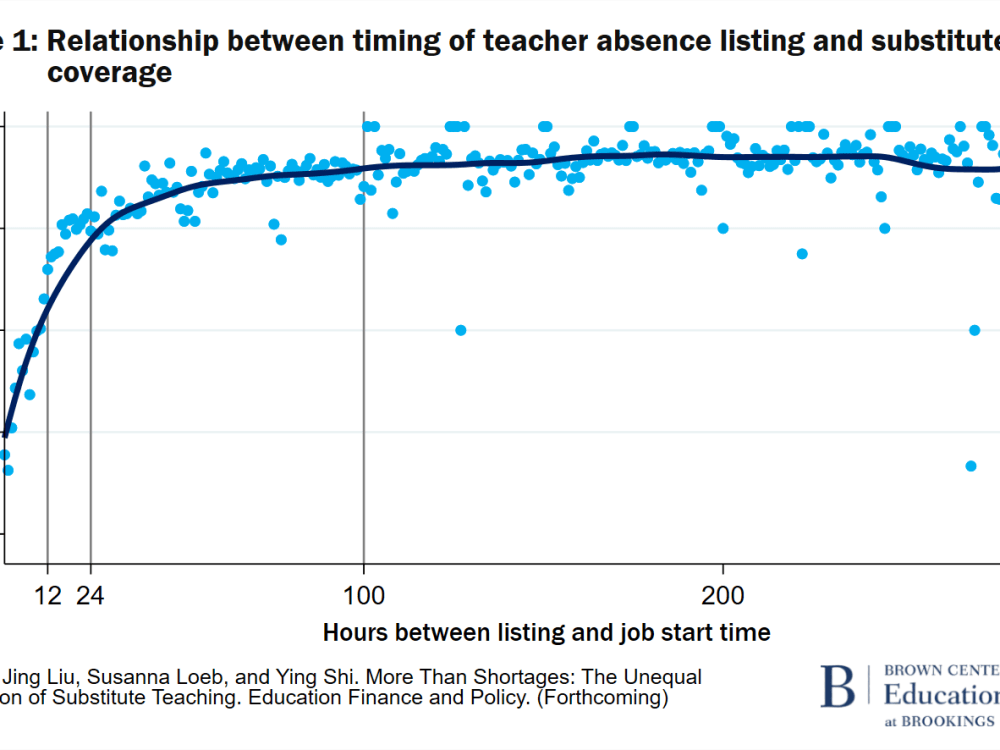

Many factors are associated with whether an absence receives substitute coverage. For example, the course subject, the timing of when a substitute job gets advertised, and teacher experiences are among the strongest predictors of substitute coverage. Schools had a harder time finding substitute teachers in math, special education, bilingual, and foreign-language classes than in other subjects. Relative to novice teachers, the more experienced a teacher is, the higher coverage rate the teacher tends to have. How early a substitute job gets posted plays another major role in absence coverage. As Figure 1 shows, the rate of improvement in coverage rates associated with an additional hour between listing and job start time is especially high through the first 24 hours, suggesting that last-minute postings are unlikely to yield high coverage. After the initial 24 hours, the coverage rate is approximately 90%.

The findings are more concerning regarding the distribution of substitute coverage across schools. To categorize student need and staffing challenges faced by schools, we used the following four dimensions:

- achievement level

- proportion of Black and Hispanic students

- average poverty rates of students’ residential census tracts

- the school district’s classification of hard-to-staff institutions, which have the greatest difficulty recruiting and retaining teachers.

In general, we found teachers in disadvantaged schools had the same number of, or slightly more, absences than teachers in more-advantaged peer institutions. By disaggregating absence types, we found that the small differences are largely driven by more absences due to professional development days at the higher-needs schools.

In contrast, disadvantaged schools exhibited systematically lower substitute coverage rates. For example, schools in the lowest achievement quartile, schools with the highest shares of minorities or students from lower-income census tracts, and hard-to-staff schools had between 0.9 to 1.3 more non-covered annual absences per teacher than do schools in the most advantaged categories. For example, a higher-needs school with 50 teachers is expected to have 65 to 80 non-covered absences annually, compared against 16 to 33 non-covered absences in an advantaged school of the same size. Our survey data confirm this finding: Teachers in higher-needs schools are much more likely to expect non-covered absences than their peers in other schools. For example, nearly half of teachers in schools with the highest share of Black and Hispanic students reported that their schools are not able or probably not able to find a substitute teacher when they are absent, while only 9% of teachers in schools with the lowest shares of Black and Hispanic students expressed such concern.

Clearly, teacher absences do not drive the unequal distribution of absence coverage. Additional analysis suggests that teacher demographics account for 3% to 5% of the overall disparities, while teacher credentials and experience explain an additional 6% to 9%. Absence characteristics, such as the timing of job postings, make a statistically significant contribution to the school disparities in some cases, with magnitudes up to 10%. The substantial variation unexplained by school, teacher, and absence characteristics suggests that factors not captured in administrative data drive the distribution we see.

Our survey administered to substitute teachers unveils many of the drivers. In the survey, we asked the respondents to nominate their most-preferred and least-preferred schools at which to work, and to write down the reasons why. Three main findings emerge.

- First, substitute teachers consistently preferred one subset of schools while avoiding another subset. The least-preferred schools were middle schools that have significantly lower average achievement, a higher concentration of Black and Hispanic students, and higher suspension rates.

- Second, the number of times a school was nominated as a most- or least-preferred school accounted for a large share (40% to 50%) of the cross-school variation in substitute coverage rates.

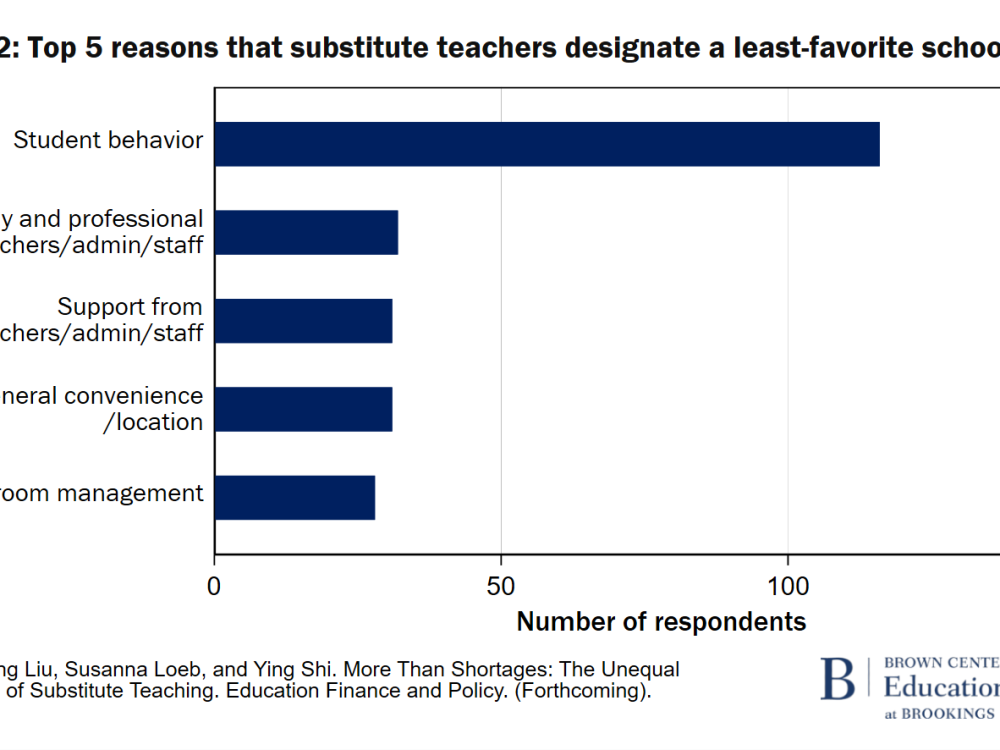

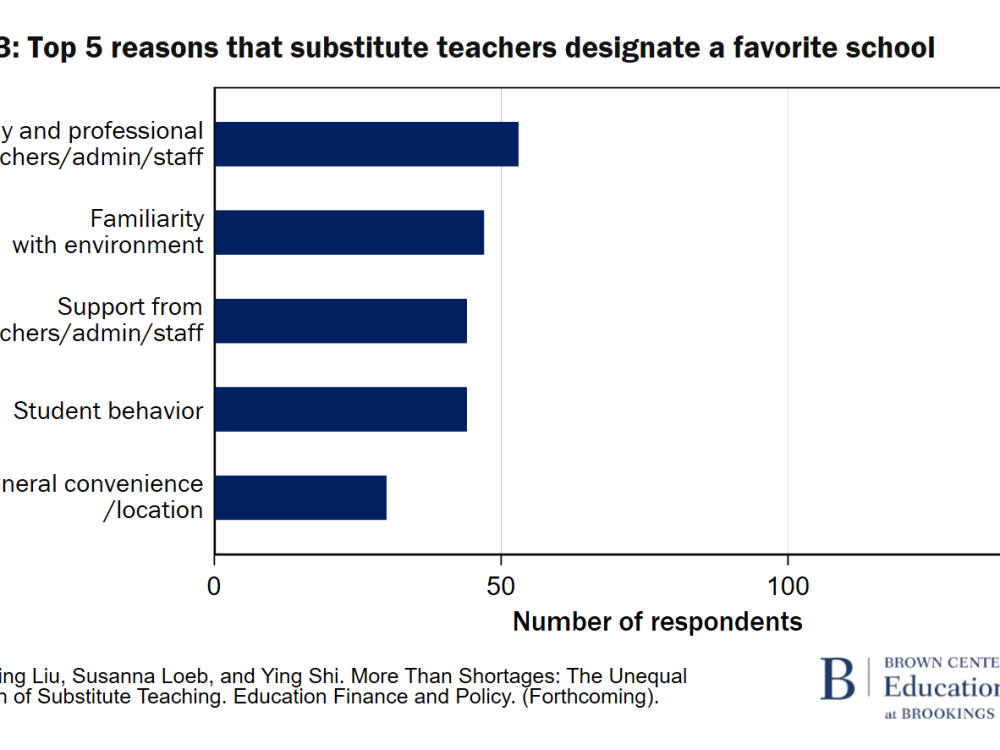

- Lastly, in their qualitative comments, substitute teachers often cited student behavior as an important factor in their determination of certain schools as least preferable (Figure 2), but mentioned a wide range of factors that can make a school desirable, such as the colleagues, well-behaved students, and familiarity with a school (Figure 3).

Given the heightened health concerns due to the COVID-19 pandemic, finding substitute teachers might become an increasingly challenging task for school leaders. On one hand, teachers might incur more absences because of various physical, psychological, and financial stressors they have been experiencing in the pandemic. On the other hand, it is unclear how willing a potential substitute teacher is to serve in a school, typically with a less-familiar working environment and unknown students. Our work shows that schools with higher needs and fewer resources had a harder time finding substitute teachers before the pandemic. These schools may now have an even greater difficulty finding substitute teachers. Thus, designing policies to address inequality in access to substitute teaching should be an integral part of school staffing plans, and merits close attention in school reopening plans.

Our findings suggest that certain strategies—such as planning around the posting of absences to avoid last-minute substitute jobs—may help close substitute coverage gaps. More importantly, given student behavior and the presence of support services from a school’s staff and administration are key determinants of whether substitute teachers favor working in a particular site, schools should ramp up their institutional efforts to provide more support for substitute teachers. This could include initiatives that curb misbehavior and provide substitutes with more classroom-management tools.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).