The 2018 year saw 29 states and Puerto Rico introduce some form of financial literacy legislation, with most focused on young people and education. The heightened priority given to financial literacy is largely driven by students’ increasing use of debt to finance college, and a perception that they lack the skills and knowledge needed to make these financial decisions. As outstanding debt has crept above the $1.5 trillion mark, and default rates show no sign of decreasing, it is important to understand whether a lack of financial literacy contributes to default, and more practically, if financial literacy efforts are targeting the right students and topics.

Unfortunately, our understanding of financial literacy for college students has been limited by a lack of national statistics or generalizable studies. Our new study, a collaboration between RTI International and the RAND Corporation, analyzes data from the National Center for Education Statistics containing 100,000 students sampled for the 2015-16 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:16). NPSAS is a study of how students and parents pay for college and has been released every three or four years since 1987; unique to this release is its inclusion of questions related to students’ knowledge of financial topics and their familiarity with student loan terms.

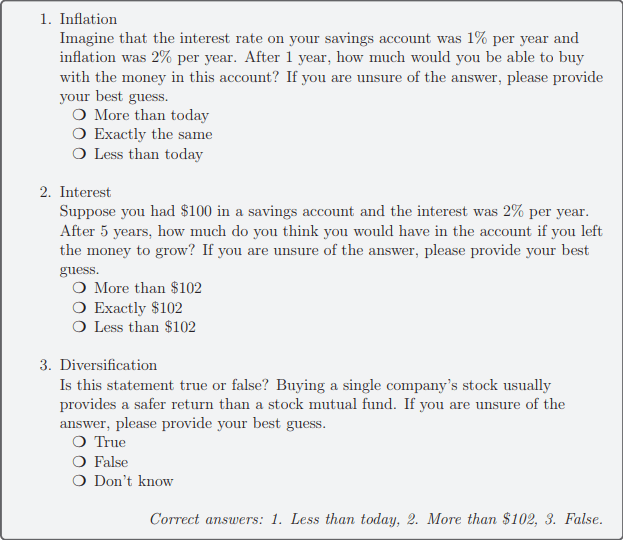

Overall, undergraduate students in the U.S. demonstrated low levels of financial literacy. When asked simple multiple-choice questions about financial investments—testing the “Big Three” concepts of inflation, interest, and risk diversification—just 28 percent got all three correct. Compare this to a national sample of American adults in which 53 percent of respondents got the same three questions correct.

Students had room for improvement across the board, but some groups scored lower than others. Financial knowledge was lower among students who were younger, in earlier years of college, of underrepresented racial/ethnic minority groups, or from lower socio-economic backgrounds. For example, students with the lowest financial security, as indicated by their reported ability to come up with $2,000 in the next month, were 40 percent less likely to answer the financial literacy items correctly, compared to students who were certain they could come up with that amount. In general, our results show disparities in financial literacy that are similar to disparities found on other dimensions using standardized tests like the ACT/SAT, where students from higher socio-economic backgrounds outperform those who are disadvantaged.

However, our findings related to student loan knowledge were less anticipated. NPSAS:16 asked students whether they knew about the consequences of student loan default and whether they were aware of income-driven repayment (IDR) plans. IDR protects borrowers when they’re unable to pay the standard monthly payment on their student loans by capping the payment at a percentage of disposable income. Most students understood that default could be harmful to their credit scores (71 percent), and that the government could collect what is owed on a defaulted student loan by garnishing their wages (53 percent) or withholding their tax refunds (63 percent). Yet, only 32 percent of students said they were aware of IDR.

The potentially encouraging news here was that borrowers were much more likely to be aware of IDR and the consequences of default than non-borrowers. More importantly, the socio-demographic disparities we mentioned with respect to financial literacy were far less striking for student loan literacy after controlling for borrowing.

Take the financial security item from a few paragraphs ago as an example. When tested on financial literacy (figure 1 below), students with the highest financial security (ability to access $2,000) performed significantly better than students with the lowest financial security, by about 15 percentage points. But whether students had borrowed loans was unrelated to financial literacy, seen through the close proximities of the hollow and solid blue dots. However, when tested on student loan literacy (figure 2 below), the reverse was true. Financial security was only marginally related to student loan literacy, but borrowers showed noticeably higher student loan literacy than students without loans, as is evident by the large gaps between the solid red dots and hollow red dots in all four categories. A similar pattern persisted for other characteristics besides financial security, like grade point average, family income, and race/ethnicity.

Figure 1: Financial literacy scores by financial security and borrowing status

Figure 2: Student loan literacy scores by financial security and borrowing status

(Note on figures: Values were obtained from predicted values from logistic regressions controlling for other student and institution-level characteristics. More details can be found in our paper.)

Even though relatively disadvantaged students tend to lag behind others in their understanding of investment concepts and applying math to personal finance, this is not the case for student loan literacy. Instead, borrowers—who come from a range of backgrounds but tend to have more financial need—understand loan terms significantly better than non-borrowers regardless of background characteristics. This finding suggests that students may be learning key loan concepts from a combination of experience borrowing, federally provided entrance and exit counseling, and services provided by their college’s financial aid office. However, even though all borrowers undergo entrance counseling to learn about student loans when they first borrow, only 43 percent of students with federal student loans were aware of IDR plans, suggesting there is more work to be done during and after college to promote options designed to help students once they enter repayment.

The relative consistency among borrowers in terms of their student loan literacy is intriguing given what we know from other research—student characteristics, like race, are significantly related to loan outcomes, like default. What’s missing is a clear picture of a possible disconnect between students’ loan knowledge versus successful repayment. General financial literacy could be one such construct that separates good from bad loan outcomes, but more likely is that “awareness” of loan items, like the consequences of default, is not enough information to prevent poor outcomes from happening. How to address gaps in this area is the 1.5-trillion-dollar question. Understanding that financial and student loan literacy are distinct and finding ways to design literacy programs with that in mind is a first step toward answering it.

Commentary

Financial and student loan (il)literacy among US college students

October 15, 2018