To increase educational attainment levels, the process of preparing and applying for college needs to improve. Students need to know when to apply for financial aid, how to choose a college that matches their academic and social preferences, and develop awareness about what happens after college in terms of repaying debt and finding a job. There are many unknowns along the way, which is why so much attention today focuses on improving students’ “college knowledge” to help them navigate this process. But even if we fixed the process of college opportunity and all students became perfectly informed consumers, inequality would persist because of education deserts.

Increasingly, research suggests that where students live impacts their likelihood of attending college. Today’s college students are increasingly place-bound, working full-time, and are balancing a number of other responsibilities while taking classes. Their choices are determined by what is nearby, regardless of how much college knowledge they may have about alternative options. For them, it is not very helpful to know that a college hundreds of miles away would be a better academic fit or provide a better financial deal than the one down the road. A more intentional focus on the influence of place on student choices is driving our early understanding of what we term “education deserts,” places in all 50 states where potential students confront limited college opportunity.

Place can trump college knowledge

College knowledge resources are often developed on the premise that better and more information about colleges, their outcomes, their prices, and their demonstrated (or undemonstrated) value-add will lead to better college choices and presumably higher rates of degree completion and student satisfaction. And that may very well be true for some students, at some institutions, some of the time; we certainly want students to consider a range of college options when identifying a best-fit.

But even students with high levels of college knowledge may find themselves having few college opportunities simply because of where they live: place is an important yet too-often overlooked factor in college opportunity. Therefore, focusing on improving college knowledge will only get state and federal policymakers so far with respect to increasing educational attainment levels.

This is because many college knowledge tools have embedded into their intent, design, and presentation to end users a presumption that student choices about where to enroll in college are regional or national in scope. In reality, enrollment data indicates that for the majority of the college-going population, education markets are highly localized; students overwhelmingly attend postsecondary institutions that are close to home.

How geographically mobile are today’s students?

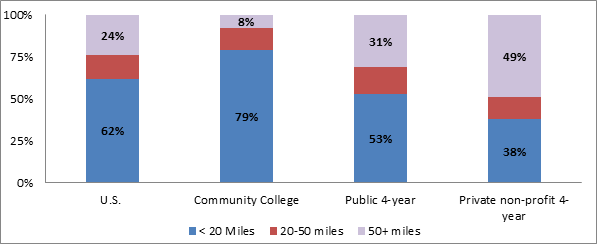

As Figure 1 shows below, the majority of undergraduates enroll in a college that is near where they live. Over half of community college (79 percent) and public four-year (53 percent) students enroll within just 20 miles from home. This of course varies by state, but illustrates the point that today’s college students are not as mobile as some may think. Today’s college students work full-time, care for dependents, and may not have the luxury to “shop around” for colleges far away from home. The majority of college students are not just that; they are parents, care-givers, employers and employees. In essence, they are grounded in their communities by factors and commitments that make moving great distances to pursue a postsecondary education difficult. Given this student profile, it is no surprise that geography, and specifically distance from home to a postsecondary institution, shape students’ decisions about whether and where to enroll.

“The majority of undergraduates enroll in a college that is near where they live. Over half of community college (79 percent) and public four-year (53 percent) students enroll within just 20 miles from home. This of course varies by state, but illustrates the point that today’s college students are not as mobile as some may think.”

Fig. 1: Distance from student’s home (in miles) to enrolled postsecondary institution

Source: NPSAS:2012 author’s calculations using “SECTOR4, DISTANCE, ALTONLN2, and WTA000”

The critical role of “place” as a factor in postsecondary policymaking

The relative “localness” of a students’ college market would be of little practical concern if local college options—and particularly public college options—were distributed evenly. But they are not. In fact, there exist a large number of “education deserts” spread throughout all 50 states, where place is likely to constrain both college going rates and by extension degree completions.

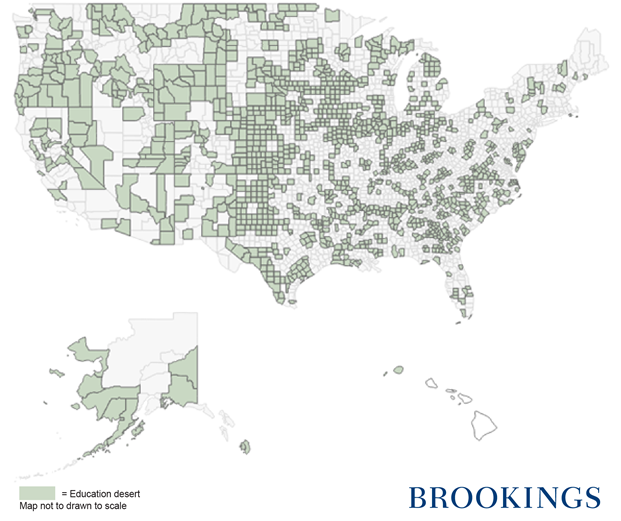

In a recent study one of us conducted, education deserts are pockets, measured at the county-level, within and among states where there is either no college or university located nearby or a single community college is the only public broad-access institution nearby. The former represents that most isolated of educational markets for students who reside in these communities, while the later reflect a prioritization on public broad-access institutions that provide the most robust and intentional postsecondary options for local communities and students. Local areas are typically measured by either commuting zones or by metropolitan/micropolitan statistical areas, so even within these areas there could be pockets of isolation. Nevertheless, education deserts are present in every state, comprised of urban, suburban, and rural counties. These deserts affect all types of students, and are home to nearly 13 million adults (Map 1).

Map. 1: All education deserts (metropolitan, micropolitan, or commuting zones) by geographic region

Source: Original maps and underlying data for Lower 48, Alaska, and Hawaii.

An example illustrates the impact of education deserts on college choice and efforts to improve educational attainment. The metropolitan area of Laredo, Texas has a population of approximately 260,000, and 94 percent of adults are Hispanic. There are four institutions nearby: one community college, one selective public four-year university, and two for-profit institutions. These four institutions collectively enroll 20,700 students with the majority (60 percent) attending Laredo Community College and the next largest number (35 percent) attending Texas A&M International University. The remaining two for-profit colleges enroll a small share of the total number of students in this metropolitan area (5 percent). For place-bound prospective students living in Laredo, their college choices are constrained to only a few options. The only alternatives to Laredo Community College are a highly selective four-year university that may be difficult to get into or two for-profit colleges that offer a very narrow set of courses and are more expensive than the community college.

In Laredo, TX, and hundreds of other communities across the nation defined as education deserts, more and better information—increased levels of college knowledge—is unlikely to show significant impact on moving a greater number of individuals into and through postsecondary education; for place-base students it is often not what is known but what is available that drives college choice and enrollment decisions.

Moving forward to address the challenge of place

As policy is designed at the state and federal level aimed at increasing postsecondary degree completion, decision makers need to be intentional about dealing with the impact that place has on student choice. To-date, geography has played a limited role in important debates about college access and attainment. By emphasizing the significance of place, policymakers might find creative and equitable ways to improve educational opportunities.

As a first-step, we encourage investigation into “where” education deserts are located. The map provided here may be a helpful first step, but states may find other communities that have limited local options. Building an inventory of education deserts is the easy task; building the capacity of colleges serving these areas is much more challenging. Perhaps new satellite campuses, public-private partnerships to develop new high-quality service providers, or engaging local high schools and employers in advance training and skill acquisition are but a few potential ways to take full advantage of local resources to build the capacity to serve local needs. Perhaps one day there could be a federal effort similar to Title I funding in public K-12 schools where underserved communities receive additional financial and technical support to bring about greater equity in postsecondary education.

Until then, conversations around building local capacity should not be clouded by an overly optimistic view that online distance education can save the day. There are persistent challenges to access and adoption of broadband that play a limiting role in reversing the deeply rooted inequalities found in the education marketplace. Place matters, and we don’t believe you can overcome its influence through technology alone.

Increasing college knowledge and students’ understanding of the process of applying to and enrolling in college is a laudable goal. Ensuring that local communities have the capacity and resources to meet educational need is equally important. A focus on the impact of place would advance our collective efforts to support broad access to a postsecondary education. For when it comes to supporting college enrollment and degree attainment, it isn’t just about what you know, it is also about where you live.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).