In America, the 1 percent are the villains. Everyone else—the 99 percent—are the good guys. Right? Not so, argues Brookings Senior Fellow Richard Reeves in a new book Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do About It. The real class divide, he says, is not between the upper class and everyone else; it is between the upper middle class and everyone else.

This separation is both economic and social, he writes, and the practice of “opportunity hoarding” is especially prevalent among parents who want to perpetuate privilege to the benefit of their children. While many families believe this is just good parenting, it is actually hurting others by reducing their chances of securing these opportunities. As Reeves shows in the book, there is a glass floor created for each affluent child helped by his or her wealthy, stable family. That glass floor is a glass ceiling for another child.

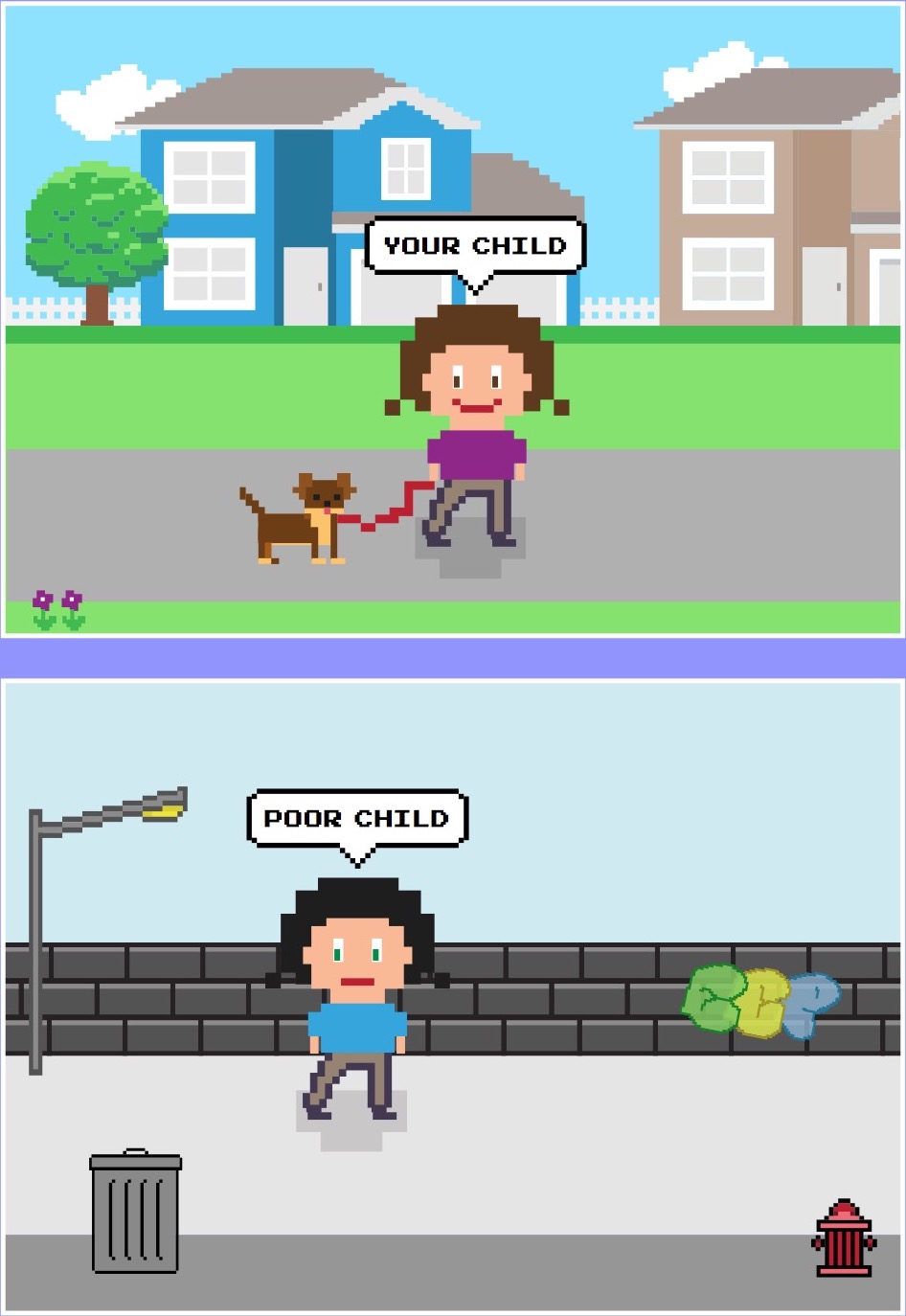

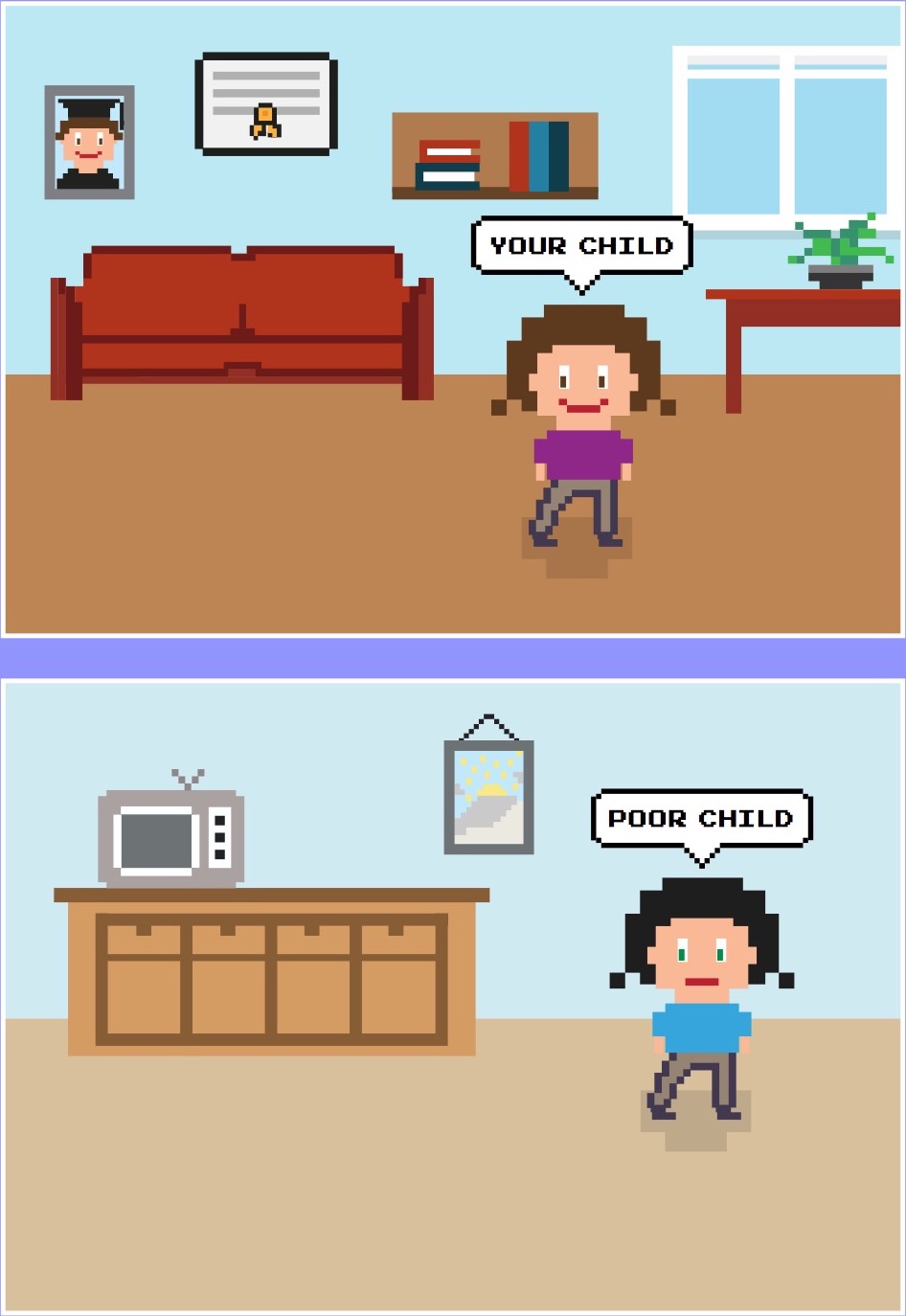

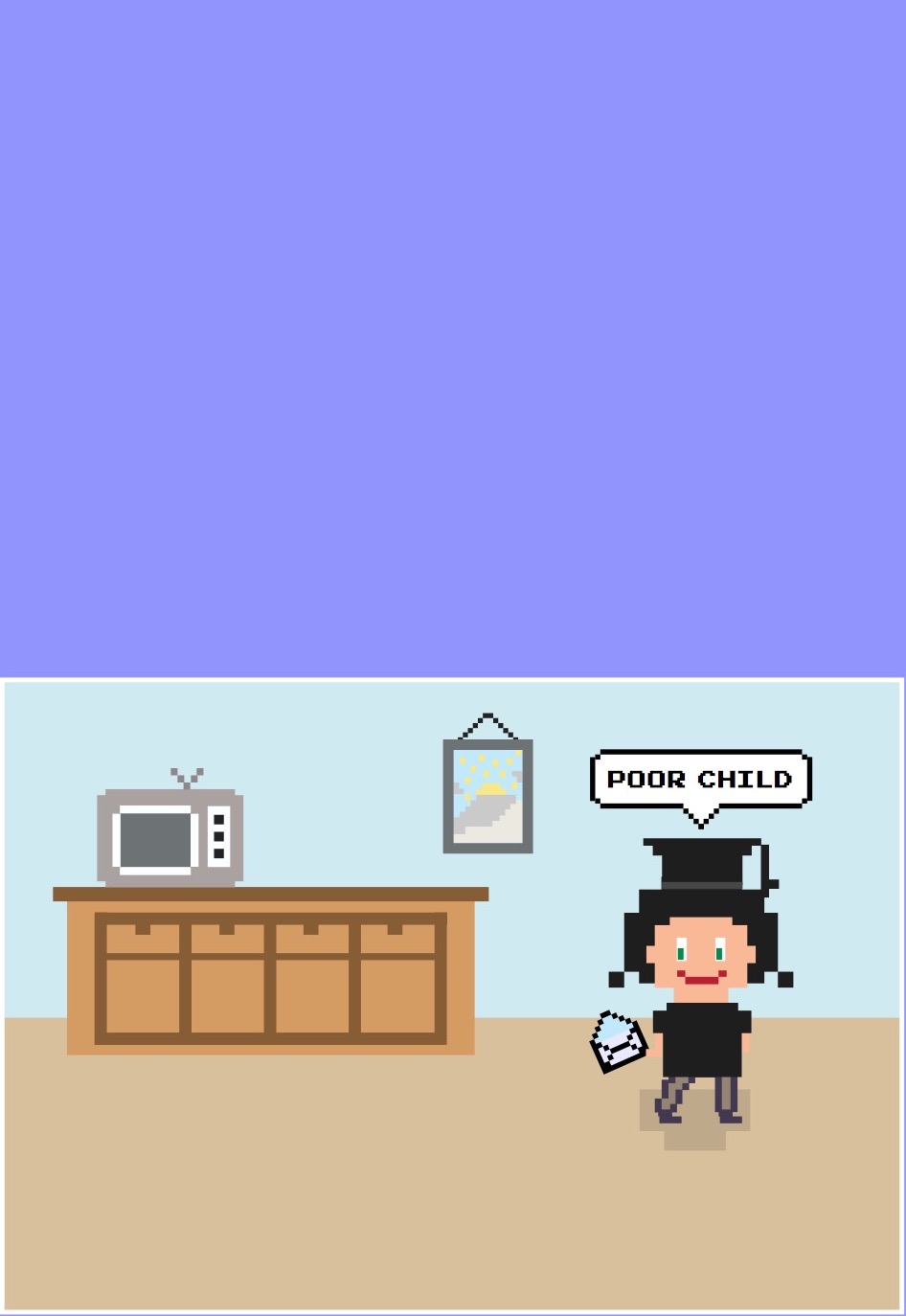

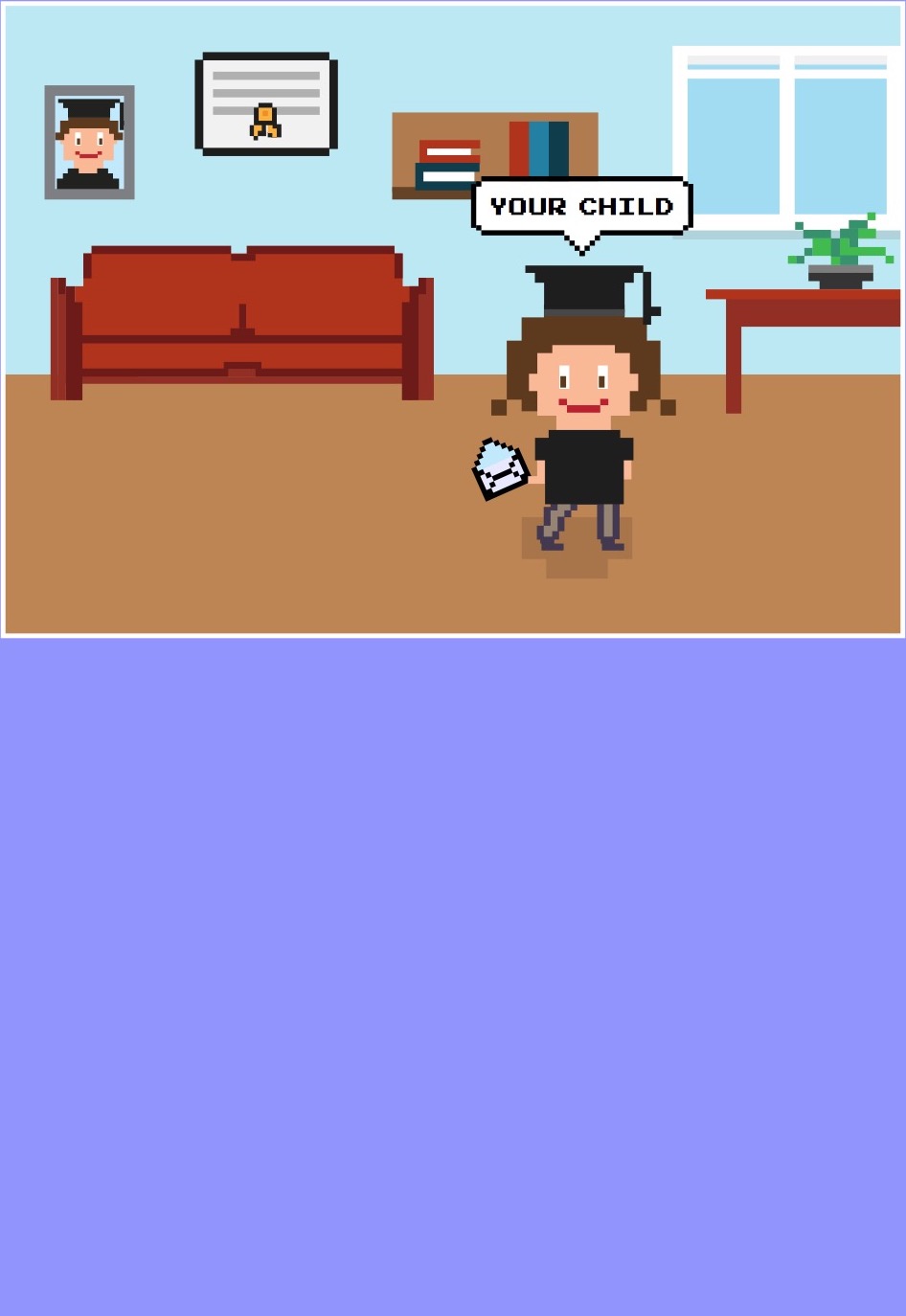

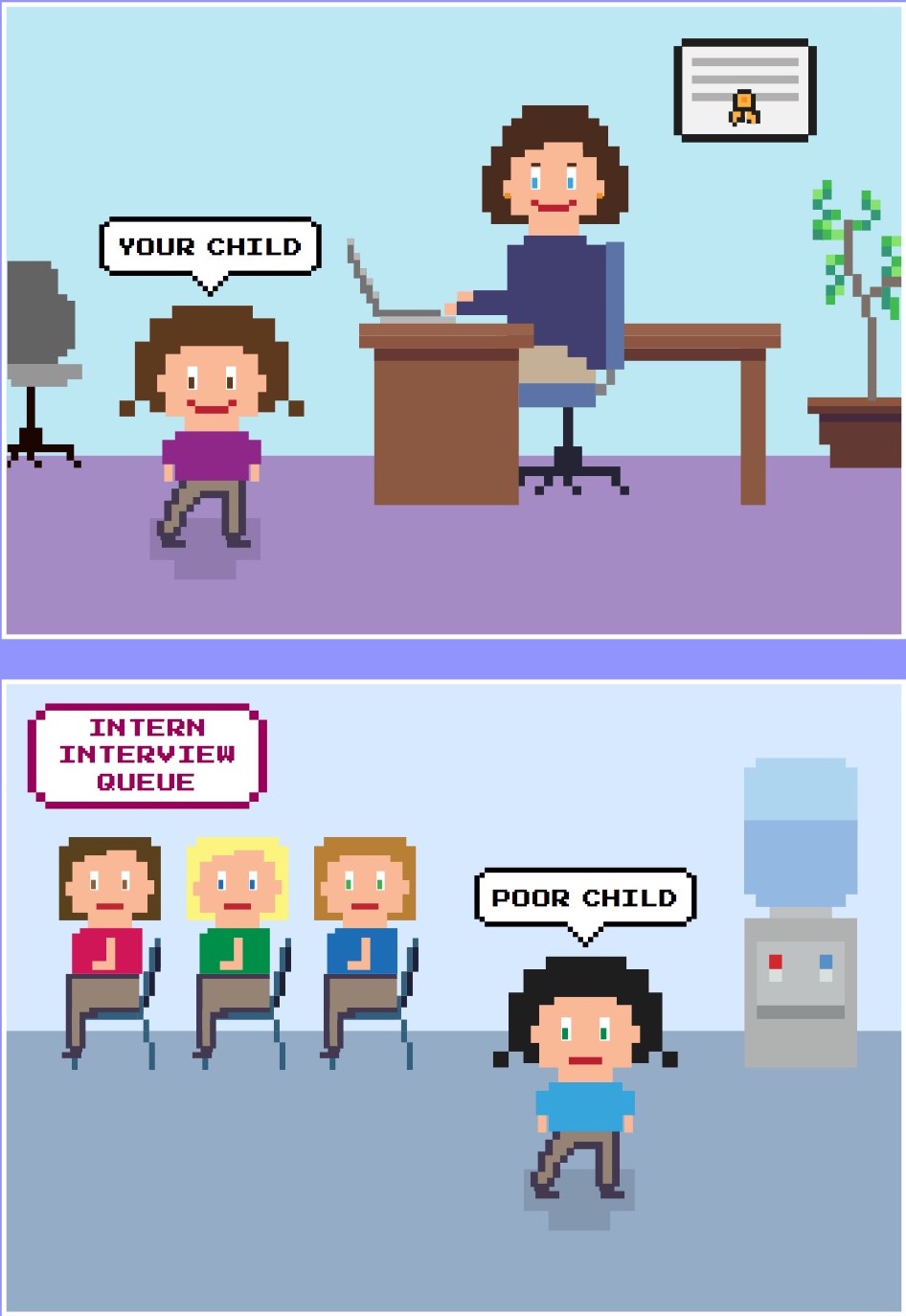

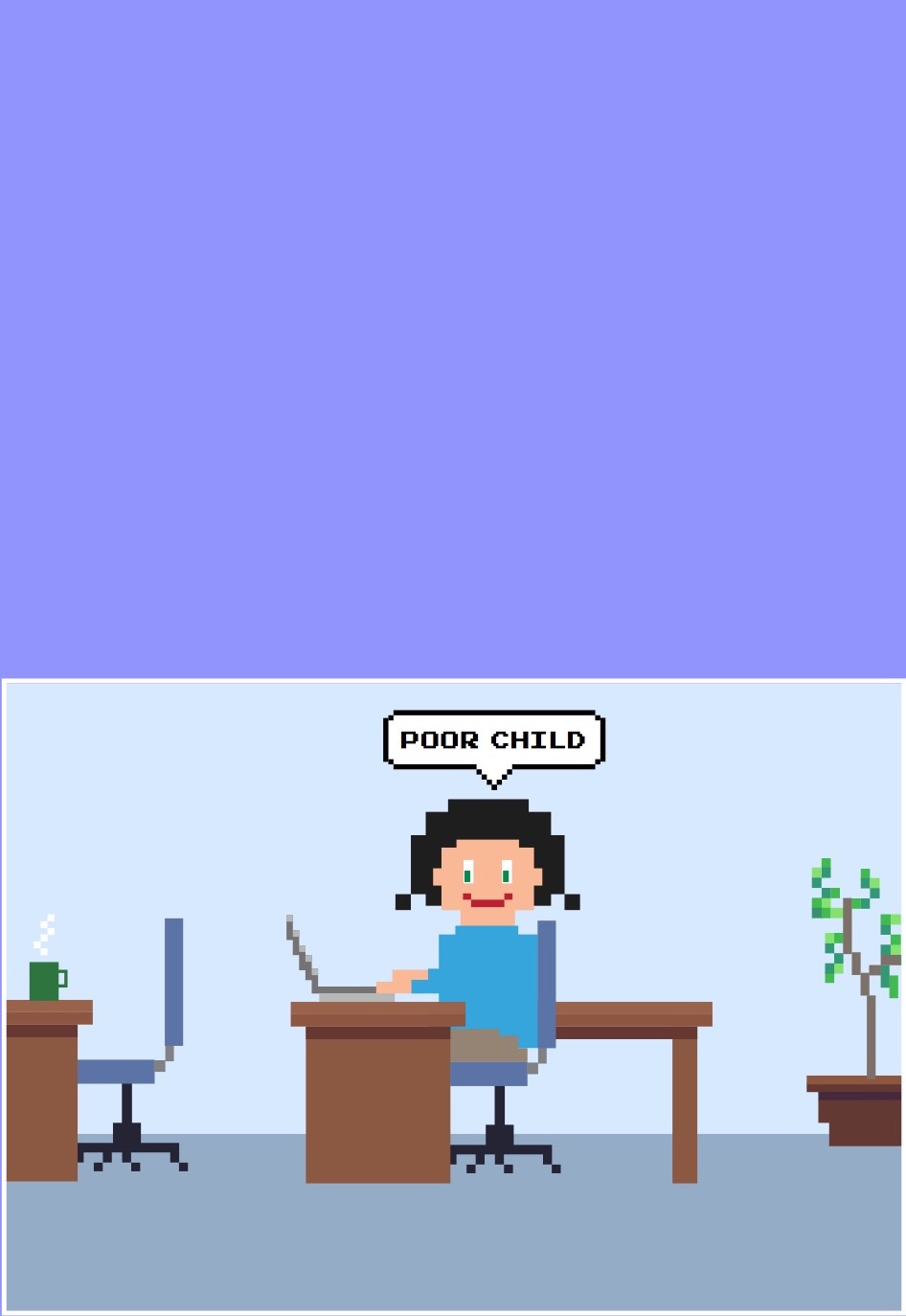

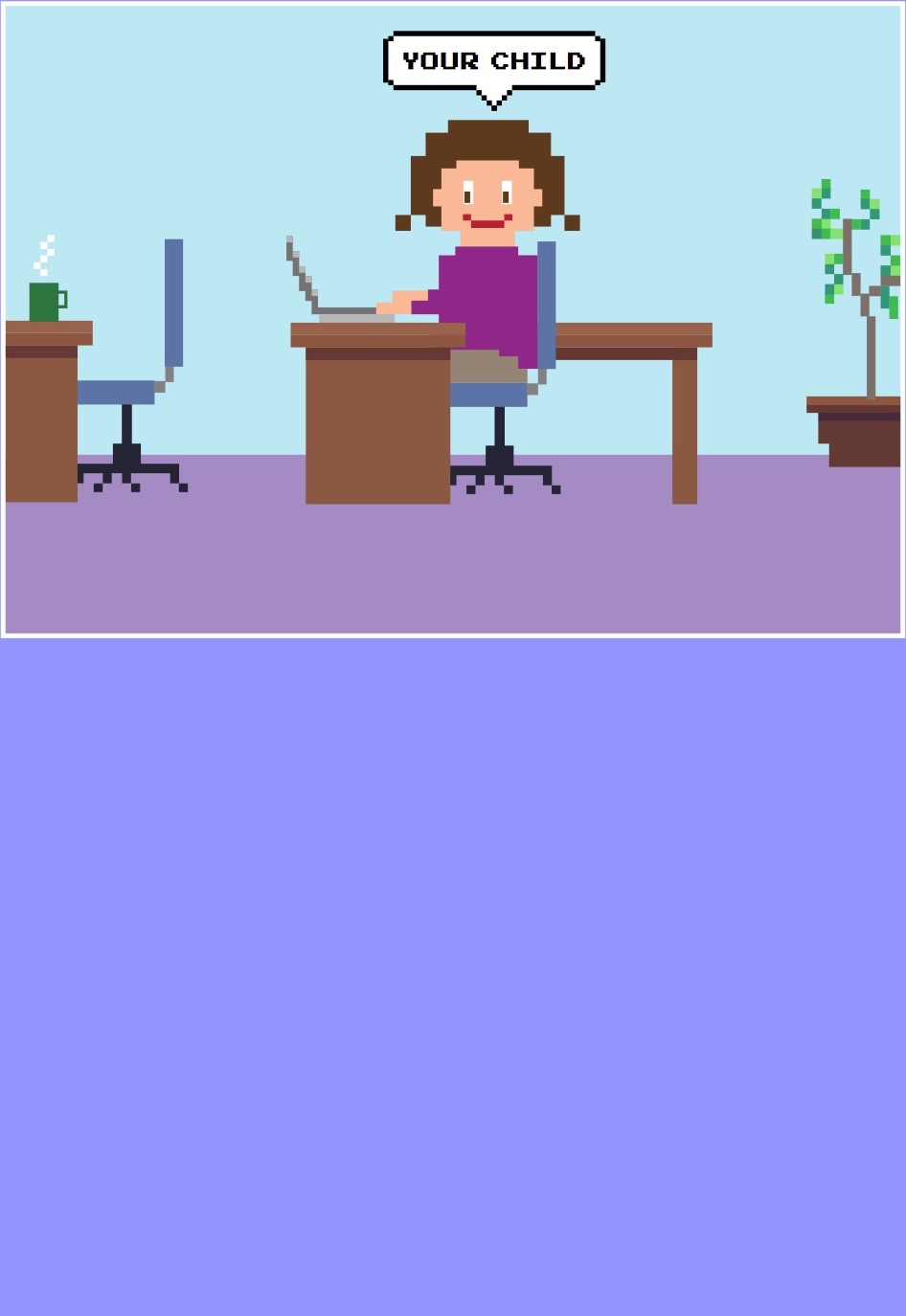

To illustrate Reeves’s argument, the Brookings Creative Lab created a short, interactive game to help you determine whether or not you are hoarding the American dream for your own child. Play it now:

Created by Jessica Pavone and Yohann Paris.

Music by Gastón Reboredo.

Inspired by “The Voter Suppression Trail.”

If you are a dream hoarder, do not fear. Reeves has a list of five things you can do right now to start increasing social mobility.

For more on Dream Hoarders, listen to Reeves on the Brookings Cafeteria podcast and buy the book.

Disclaimer: To create this game, we simplified the situations that would determine whether or not you are hoarding opportunities for your children. Please read Dream Hoarders for context and the evidence-based research behind the questions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Play the Dream Hoarders game

July 13, 2017