In early June 2021, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari announced the indefinite suspension of Twitter after the platform deleted one of his tweets and temporarily suspended his account. The tweet pertained to Nigerian secessionists and to treating “those who misbehave today” in “the language they will understand,” infringing on Twitter user rules prohibiting content that threatens or incites violence. Despite the ban, many Nigerians still have access to the site using virtual private networks (VPN) and can share their opinion on other apps, like Indian-based microblogging site Koo.

The deletion of the tweet is part of a larger conversation around the role of social media in politics and the national conversation. Indeed, in recent years, the world has seen social media platforms like Twitter impact democracy and politics, social movements, foreign relations, businesses, and economies around the world.

President Buhari’s retaliation sparked massive global and national reactions. In this piece, we analyze the reaction of Twitter users to this move using a collection of over 2.6 million tweets generated from June 4 to June 11, 2021 that contain any mention of “Nigeria” (details on the methodology can be found at the end of the blog).

Tweets within the collection pertained to several overarching topics like the ongoing kidnappings of school and university students or the #EndSARS movement that helped mobilize a campaign to end policy brutality. However, the majority of the tweets were focused on the government’s ban of Twitter, which expressed concern over the move and its implications for the state of Nigeria’s democracy. Many tweets criticized President Buhari’s actions as an infringement on their freedom of expression and access to information—both crucial pillars of democracy.

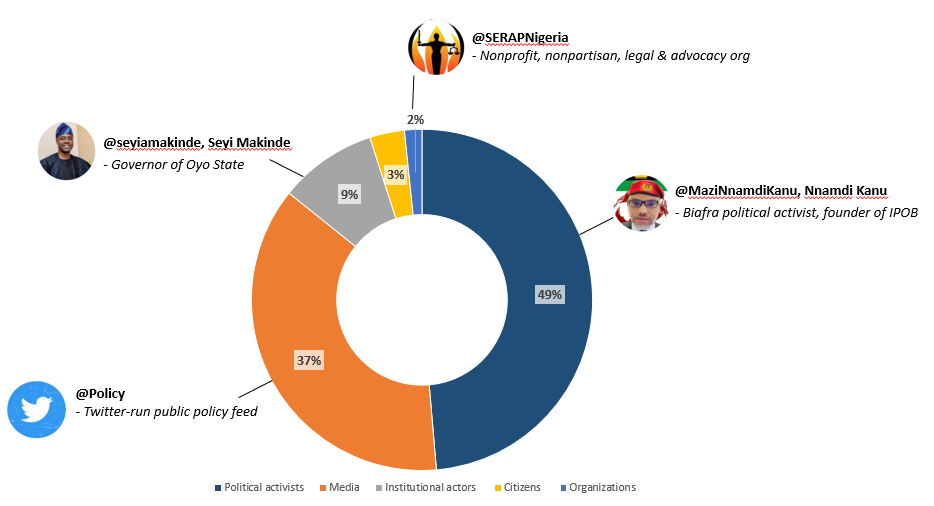

Notably, most content on Twitter is not original, as users with a large follower base drive the discussion through retweets, likes, and comments; in fact, 85 percent of tweets in this collection are retweets. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the top 50 retweeted users, encompassing over 30 percent of the 2.6 million tweets, which can give insights into who has the most input within the conversation. Over 49 percent of the top users are political activists like Nnamdi Kanu, who was actually the most retweeted account within the collection. (Nnamdi Kanu founded the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a movement to create an independent state in southern Nigeria.) Media blogs and journalists comprise the second-largest share of top users, with accounts like the Twitter Public Policy feed and news coverage from both Nigerian and international media outlets.

Figure 1. Top 50 most retweeted users in collection

Source: Authors, using data from Twitter.

Political activists have the most dominant voice in the conversation while institutional actors and organizations have some of the smallest. While Nigerian citizens and activists continue to use the platform, the Nigerian government has effectively shut itself out from the conversation with only the governor of Oyo State, Seyi Makinde, still maintaining a presence on Twitter.

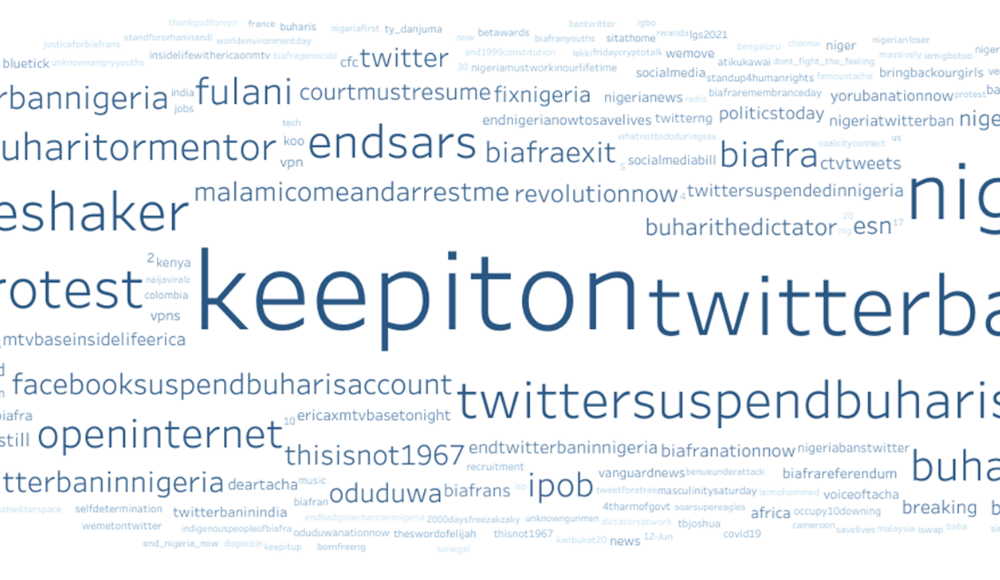

Importantly, hashtags are a powerful way to voice an opinion or bolster a movement, as seen with the #EndSARS protests that broke out in October 2020. Taking a deeper look at the content of the tweets, as seen in Figure 2, #keepiton, #twitterban, #openinternet, #june12protest, and #twittersuspendbuharisaccount are some of the most popular hashtags.

Figure 2. Hashtag usage in response to Twitter ban

Source: Authors, using data from Twitter.

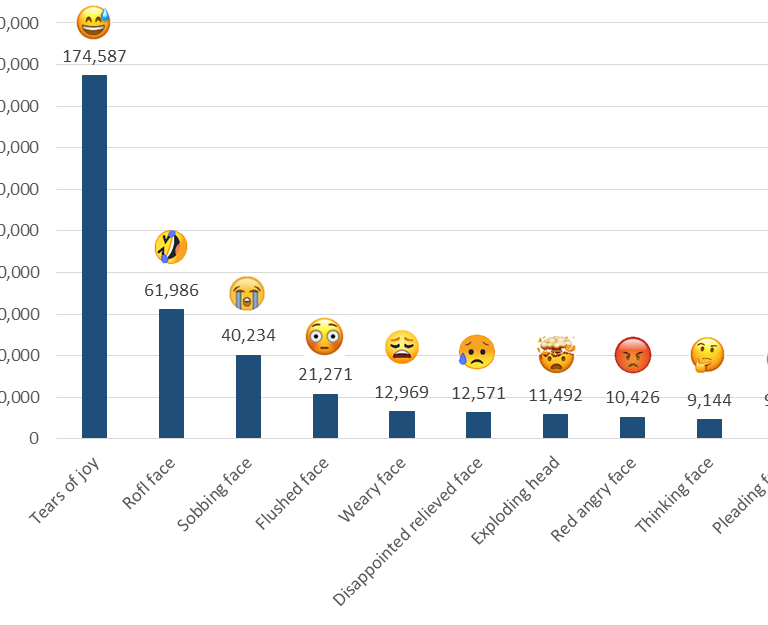

Emoji usage within the tweets can also offer insights into the reactions, with a focus on the “yellow face” emojis that can correlate to six primary emotional categories: surprise, sadness, disgust, fear, anger, and neutral. Figure 3 shows the top 10 face emojis used in the collection, with “tears of joy” being the most popular. Both of the laughing emojis typically correspond to tweets that show disbelief of the president’s ban or chided his actions with tweets like: “Using Twitter to announce the suspension of Twitter in Nigeria.” Other prominent emojis include the “sobbing face,” primarily corresponding to tweets remembering the Lekki Toll Gate Massacre and responding to the Twitter ban. Emojis like the “red angry face” are more specifically used in discussion of the ban as misplaced priority of the government when the nation is struggling with many more serious issues like poor infrastructure (particularly shortages of electricity), corruption, weak institutions, and increased insecurity and mass student kidnappings.

Figure 3. Top 10 emojis used in response to Twitter ban

Source: Authors’ calculations using data from Twitter.

Nearly 70 percent (over 850,000) of the tweets with location entries are from Nigeria, with the most common locations being Lagos, Aduja, and “Biafra”—a former secessionist state in the southeast region of Nigeria. While the discussion is primarily centered in Nigeria, many tweets are from users all over the world, with the top three countries after Nigeria being the United States, United Kingdom, and India. Within Africa, countries like Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya have the highest rates of tweets discussing the ban in Nigeria, and their responses largely echo the same concerns and anger as the rest of the world.

This brief examination reveals that this move has led to damage of Nigeria’s image on the world stage, as key diplomatic and economic allies like the EU and U.S. have condemned the ban at a time when the country “needs to foster inclusive dialogue and expression of opinions, as well as share vital information in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic,” according to the U.S. embassy in Nigeria. The global spotlight from the ban also highlights the government’s evident ineffectiveness in addressing serious economic, social, security, and political challenges.

The ban can also harm Nigeria’s growth as foreign investors pivot business and funding to other African countries, jeopardizing Nigeria’s role as the unofficial tech hub of Africa. In a recent example, Twitter chose Ghana for its regional headquarters even though Ghana has a much smaller population and economy than Nigeria but was perceived to have an attractive environment for external investors. Many startup business models also require an active social media presence, which may make it more difficult for Nigerian technology entrepreneurs to attract investors.

Small- and medium-sized Nigerian businesses have been particularly affected, as they rely on Twitter to raise awareness of their brands and for customer service and other engagement. According to Telecompaper, Nigeria’s e-commerce sector has lost over 2 billion naira ($4.86 million) daily since the ban, as businesses have had to severely cut their operations or stop them completely, otherwise risking potential fines and arrest. These losses put added pressure on an already volatile Nigerian economy, as unemployment rates reach 35 percent—among the world’s highest—particularly affecting its youth.

These events add to a concerning global trend of tightening information access and freedom of expression as countries like Ethiopia and Uganda create barriers through internet shutdowns ahead of presidential elections or internal conflict, and other countries like India, Vietnam, and Thailand recruit “cyber crime volunteers” and censor social media in an attempt to deal with vague issues like “fake news.” Nigeria’s Twitter ban, while hurting its citizens and alienating its allies, can embolden other nations to take similar authoritarian steps to discourage civic dissent and restrict essential components of a democratic society.

Note on methodology: This study utilizes a collection of over 2.6 million tweets that contain the mention of “Nigeria” generated from June 4th to June 11th 2021, and were archived using the open-source program called Twarc. Each tweet contains more than 150 different data variables but for the analysis shown here, we focus on the time when the tweets was created, location of the user, the full text of the tweet or retweet, and who originally generated the tweet. Hashtag and emoji usage were extracted from the full text of the tweet, the emojis were converted from Unicode to their written-out names and the hashtags were formatted to account for inconsistencies in spelling and capitalization. A greater discussion on the methodology and drawbacks of Twitter data can be found in the blog “How misinformation spreads on Twitter.”

Commentary

Nigeria’s Twitter ban is a misplaced priority

August 11, 2021