Africa’s energy challenges are immense. Power shortages diminish the region’s growth by 2-4 percent a year, holding back efforts to create jobs and reduce poverty. In addition, despite a decade of growth, the power generation gap between Africa and other regions is widening.

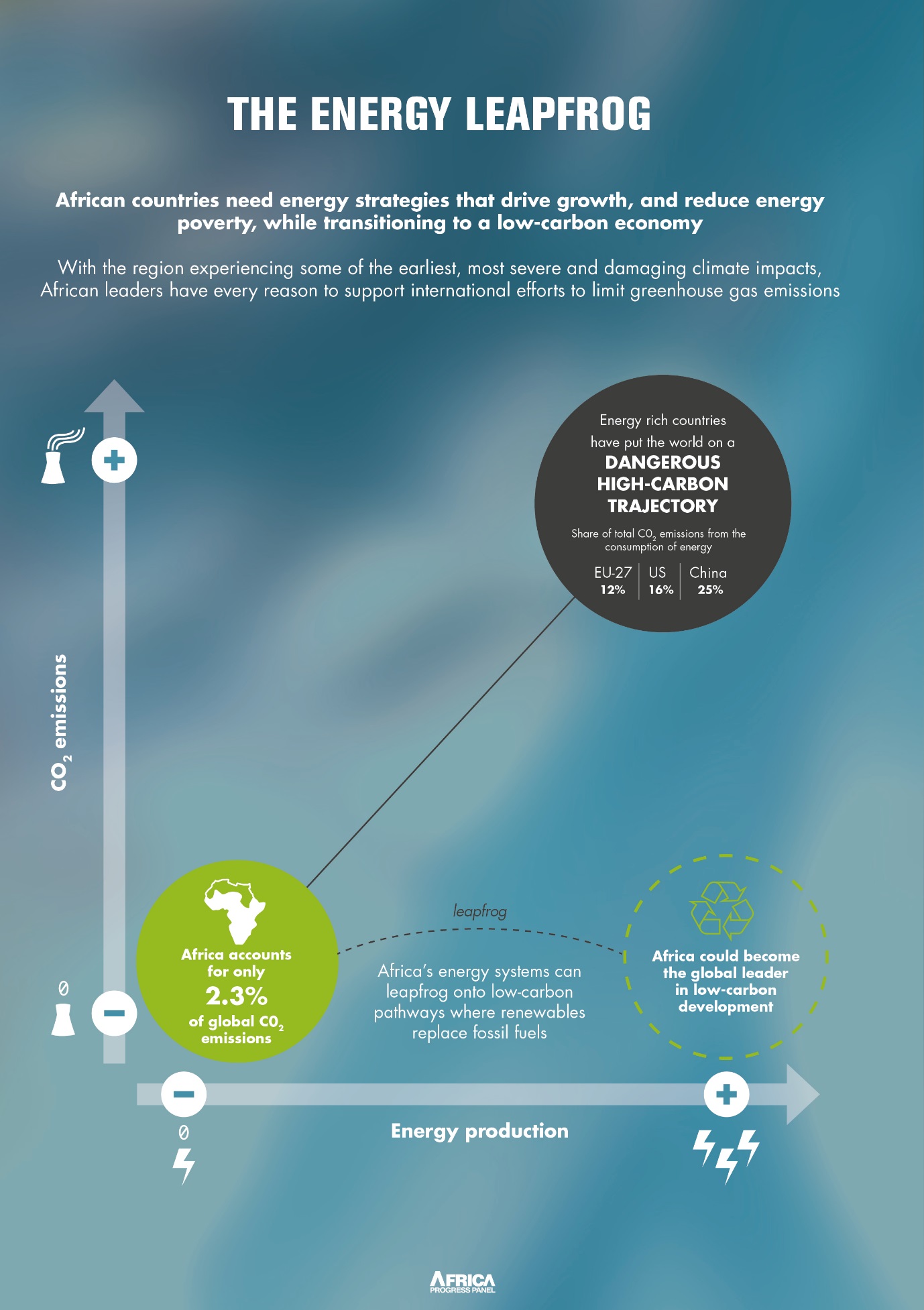

Can we stave off catastrophic climate change while building the energy systems needed to power growth, create jobs, and lift millions of people out of poverty? That’s a crucial question for Africa. No region has done less to contribute to the climate crisis, but no region will pay a higher price for failure to tackle it. At the same time, over half of Africa’s population lacks access to modern energy.

Africa’s leaders have no choice but to bridge the energy gap—urgently. They do have a choice, though, about how to bridge the gap. Africa can leapfrog over the damaging energy practices that have brought the world to the brink of catastrophe—and show the world the way to a low-carbon future. Africa stands to gain from developing low-carbon energy, and the world stands to gain from Africa avoiding the high-carbon pathway followed by today’s rich world and emerging markets.

The December 2015 talks in Paris on a new global climate treaty are approaching fast. A coherent set of common African demands is essential if the world is to raise the level of ambition needed for the Paris talks to end with a viable global climate agreement.

Source:

The Africa Progress Panel

.

The Africa Progress Panel, chaired by Kofi Annan, spells out in its latest report the bold action required from African leaders, their international partners, and the private sector. The report, Power, People, Planet: Seizing Africa’s Energy and Climate Opportunities, outlines facts and actions to change Africa’s energy future.

Ten key facts: Africa’s energy and climate challenges

1. Over 620 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa have no access to electricity. And this number is rising.

2. Today, Africa accounts for just under half of the unconnected worldwide. By 2030, two in every three people in the world lacking electricity will be African.

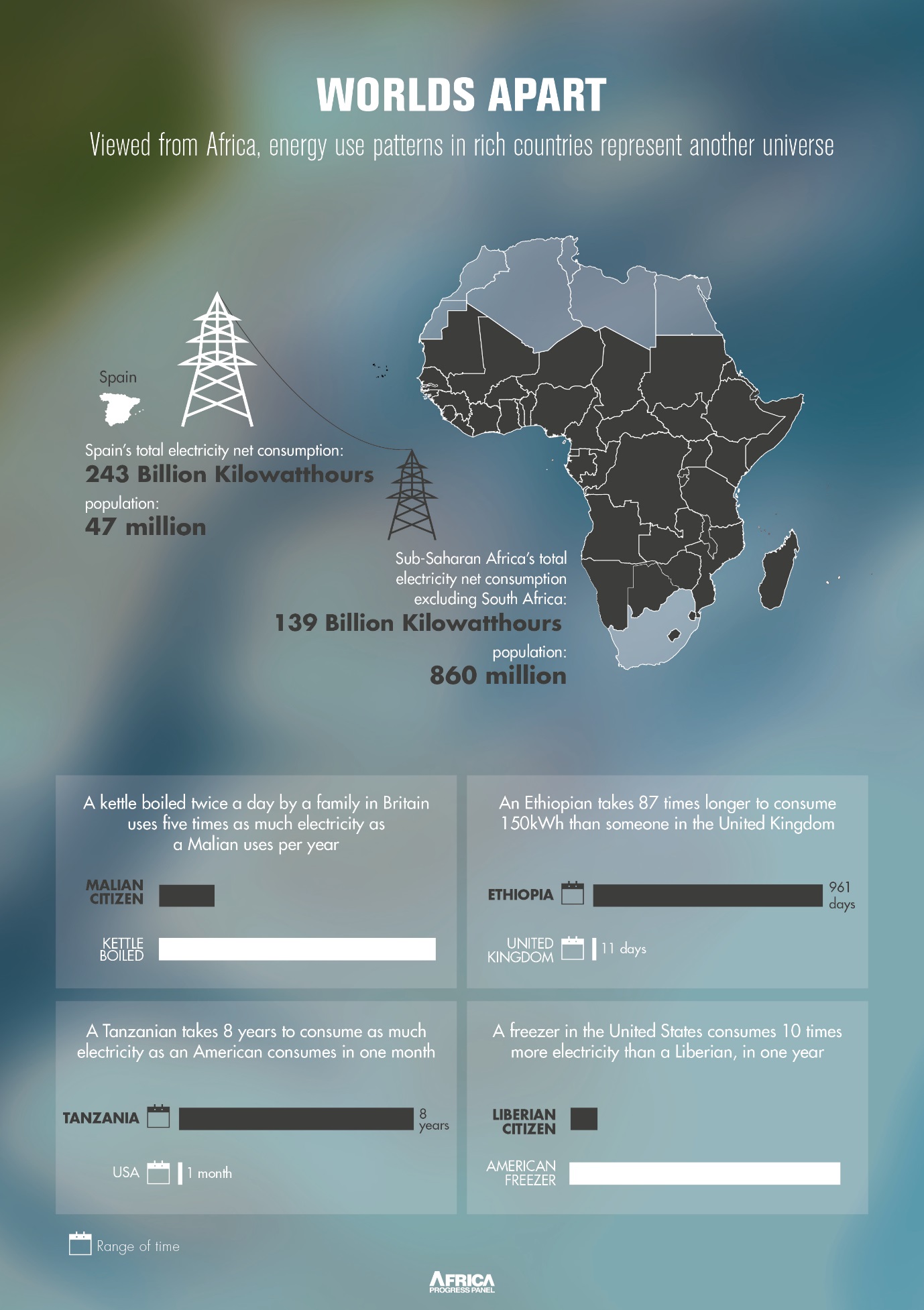

3. Excluding South Africa, which generates half the region’s electricity, sub-Saharan Africa uses less electricity than Spain.

4. It would take the average Tanzanian eight years to use as much electricity as the average American consumes in a single month.

Source: The Africa Progress Panel.

5. The use of wood for cooking is implicated in some 600,000 deaths annually through household air pollution and contributes to climate change through deforestation. Half of these deaths are children under five years old.

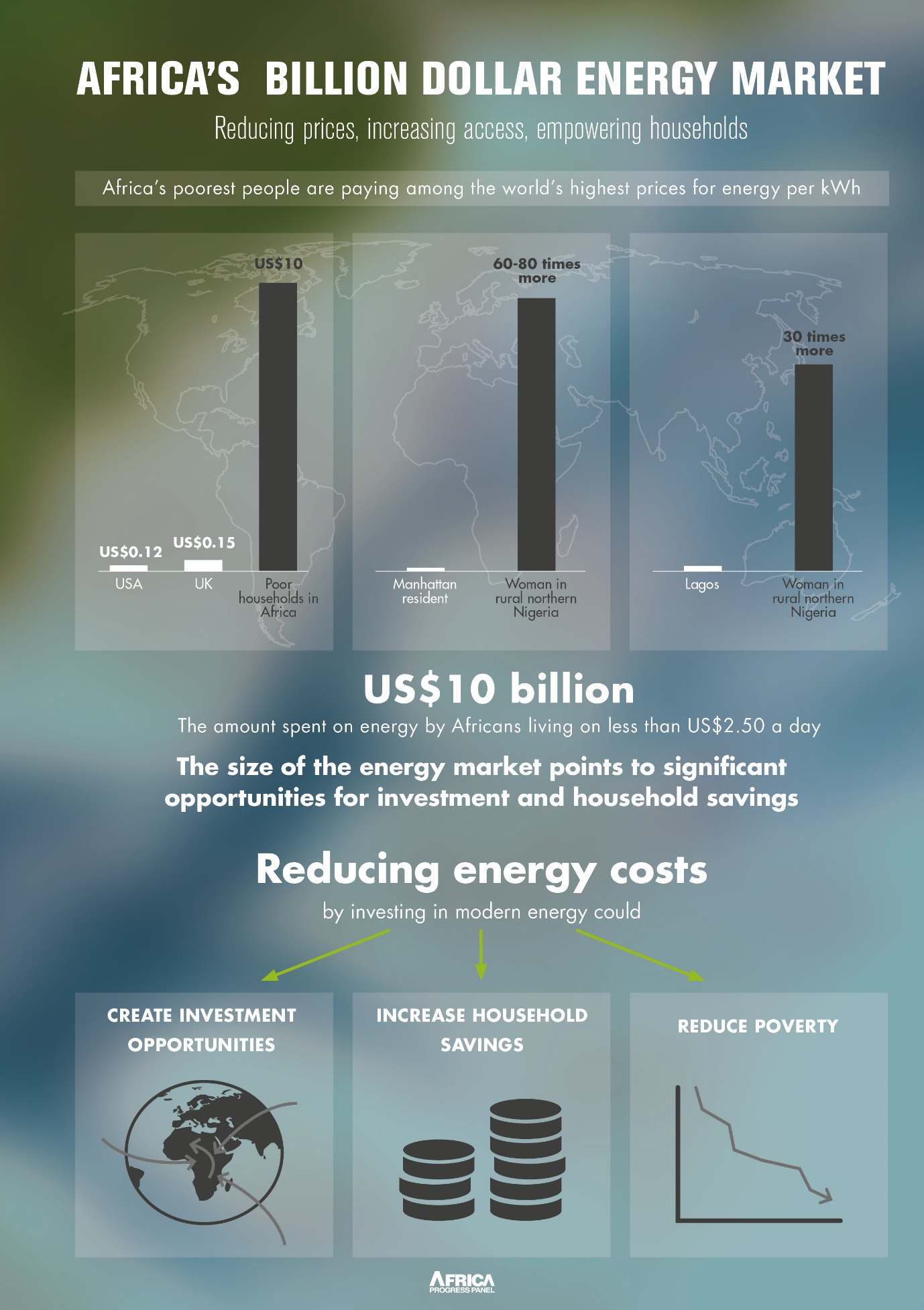

6. Households living on less than $2.50 a day collectively spend $10 billion every year on energy-related products, such as charcoal, kerosene, candles, and torches.

7. Africa’s poorest households are spending around $10 per kilowatt-hour on lighting—20 times more than Africa’s richest households. By comparison, the national average cost for electricity in the United States is $0.12 per kWh and in the United Kingdom is $0.15 per kWh. This is a significant market failure—but also an incredible opportunity.

Source: The Africa Progress Panel

8. Africa’s energy sector financing gap is estimated to be $55 billion annually to 2030. A tenfold increase in power generation is needed to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of universal access to energy by 2030; if current trends continue, the goal won’t be reached until 2080.

9. Sub-Saharan Africa (minus South Africa) accounts for only 2.3 per cent of total global emissions of greenhouse gases.

10. It would take the average Ethiopian 240 years to register the same carbon footprint as the average American.

Ten key actions for achieving Africa’s low-carbon future

- Cut pro-rich subsidies.

African governments need to phase out the $21 billion in energy subsidies geared towards the rich. Subsidizing connections for the poor is more efficient and equitable than subsidizing energy consumption by the rich, and subsidizing kerosene is of limited value as a tool for achieving universal access. For low-income households, kerosene is the most common source of lighting, but it is also one of the least efficient. On a unit-of-energy equivalent basis, kerosene is 150 times more expensive than even the least efficient incandescent bulb. Subsidizing consumption of fossil fuels distorts energy pricing, incentivizes overconsumption, deters investment in renewable energy, creates unsustainable fiscal costs, and locks households and energy systems into inefficient fuel-use patterns that perpetuate the underlying energy crisis.

Phase out fossil fuel subsidies in G-20 countries.

In 2013, G-20 countries provided $88 billion in fossil fuel subsidies for exploration and production alone. Governments in the major emitting countries should place a stringent price on emissions of greenhouse gases by taxing them, instead of continuing to effectively subsidize them. Eliminating subsidies for fossil fuel exploration and production—especially coal—should be a priority.

Increase tax revenues.

One of the greatest barriers to the transformation of Africa’s power sector is the low level of tax collection and the failure of some African governments to build credible tax systems. Almost half of this gap could be covered by increasing sub-Saharan Africa’s tax-to GDP ratio by 1 percent of GDP. Tax concessions should also be removed. Many countries provide foreign investors with excessively generous tax breaks in the form of tax holidays, capital-gains tax allowances, and royalty exemptions.

Cut corruption and reform energy utilities.

Sustained regulatory reform is critical for investment. Unbundling power generation, transmission, and distribution is one step towards creating more efficient and stable energy markets. Independent regulation is another.

Seize the low-carbon opportunity.

Governments should strengthen the market for low-carbon energy through predictable off-take arrangements, utility purchase arrangements, feed-in tariffs, and auctions. Recognizing that the initial capital costs of renewable energy investment can be prohibitive, governments and regulators should seek to reduce risks and support the development of the market through appropriately subsidized loans.

Restore degraded agricultural land.

This recommendation would raise small-holder income, reduce vulnerability, and strengthen national food security. There would be significant global benefits stretching beyond Africa in the form of reduced emissions related to agriculture, forestry, and land use. Africa has the potential to demonstrate global leadership in this area, which is of vital importance for international efforts to combat climate change.

Combat illicit financial flows, including tax evasion.

In 2012, Africa lost $69 billion from illicit financial flows. G-8 and G-20 countries must act on past commitments to strengthen tax-disclosure requirements, prevent the creation of shell companies, and counteract money laundering.

Overhaul the climate finance architecture.

Climate finance has failed Africa. It is both chronically underfinanced and fragmented. The separate multilateral agencies offering facilities to support adaptation should be merged into a single facility, perhaps under the auspices of the Green Climate Fund. Rich countries should set a clear timetable for delivering by 2020 the outstanding $70 billion per annum in climate finance.

Boost aid.

Aid can play a supportive, catalytic role. Aid donors should commit to the longstanding target of devoting 0.7 percent of gross national income (GNI) to aid. African governments should mobilize around $10 billion to expand on-grid and off-grid energy access. The international community should match this effort through $10 billion in aid and concessional finance aimed at supporting investments that deliver energy access to populations that are being left behind.

Unlock private finance.

Development finance could play a more catalytic role in attracting investment. Risk-guarantee provisions should be increased and coordination strengthened among international financial institutions, development finance agencies, and bilateral donors.

Once strong global development goals are in place, backed by smart financing and a fair climate deal, African countries will be in a better position to rethink their energy policies and transform their economies. And the continent’s energy potential will transform lives. Indeed, countries like Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, and South Africa are already emerging as frontrunners in the global transition to low-carbon energy.

For more on this issue, see the video by Kofi Annan, chair of the Africa Progress Panel, on Power People Planet.

Note:

Caroline Kende Robb is the executive director of the

Africa Progress Panel

, a foundation chaired by Kofi Annan. This blog reflects the views of the author only and does not reflect the view of the Africa Growth Initiative.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Africa can show the world the way to a low-carbon future: 10 facts, 10 actions

August 17, 2015