In June, the attorneys general of Texas and nine other states (along with one governor) signed a letter asking President Trump to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which was established by an executive order President Obama signed in 2012.

DACA provides legal protection from deportation to undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. without documentation as children (often referred to as “Dreamers”). Applicants must meet specific requirements to be eligible for the program. Although the program does not provide permanent lawful status to applicants, it provides a temporary relief from deportation, along with a social security number and work permit for a two-year period. After this period, DACA applicants can renew their status.

Low potential for federal action on DACA

If Trump does not rescind DACA by Sept. 5, the Texas-led coalition has threatened to sue the Trump administration to end the program. (According to the letter, they would amend an ongoing lawsuit to include DACA.) In response to this threat to the program, under which about 750,000 people have received protection from deportation, a bipartisan group of senators have introduced the DREAM Act, a law that would provide a path to citizenship for the individuals currently eligible for the DACA program. To say the law’s chances of passing are slim is an understatement–members of Congress have introduced iterations of this bill since 2001 without successfully passing a law. In the current political climate, passing a controversial, landmark bill of this nature seems unlikely.

If there is not much reason to expect legislative movement on this issue, what policy changes might result from the public intraparty showdown between Republican state leaders and President Trump? President Trump faces a choice: end DACA, or face a lawsuit over the program from a coalition of Republican state officials.

Given Trump’s apparent reluctance to end DACA and his expressed desire to “deal with DACA with heart,” it seems unlikely—although not impossible—that he would cave to the Republicans’ demand. If the Texas-led coalition in turn makes good on its threat to sue the administration over DACA, the future for people receiving deferred action status will remain unclear while the case works its way through the court system.

In short: Despite the demand to rescind the executive order and introduction of the DREAM Act, there may not be conclusive action from the federal executive or legislative branch anytime soon. But, this recent chain of events could have implications for students’ access to college and for state policy.

DACA and access to higher education

DACA can increase accessibility to higher education for undocumented students. At the most basic level, deferred action may encourage students to apply for college in the first place without fear of deportation. Further, work permits available through the program may enable them to get a higher-paying job, which in turn could help them finance higher education more easily. This benefit is particularly important since many DACA-eligible individuals are from low-income families, and undocumented individuals do not have access to federal financial aid. Finally, the work authorization available through DACA may help undocumented immigrants with college degrees improve future employment opportunities and earnings. As the Center for American Progress reports, “People who receive temporary work permits end up with 8.5 percent higher wages, on average.”

Potential state action on higher education access

In the wake of the letter demanding that Trump rescind the program, it is conceivable that some states may take what steps they can to expand access to higher education for undocumented immigrants. Although state governments do not have authority to provide deferred action on deportation, states can take such actions as making in-state tuition available to undocumented students.

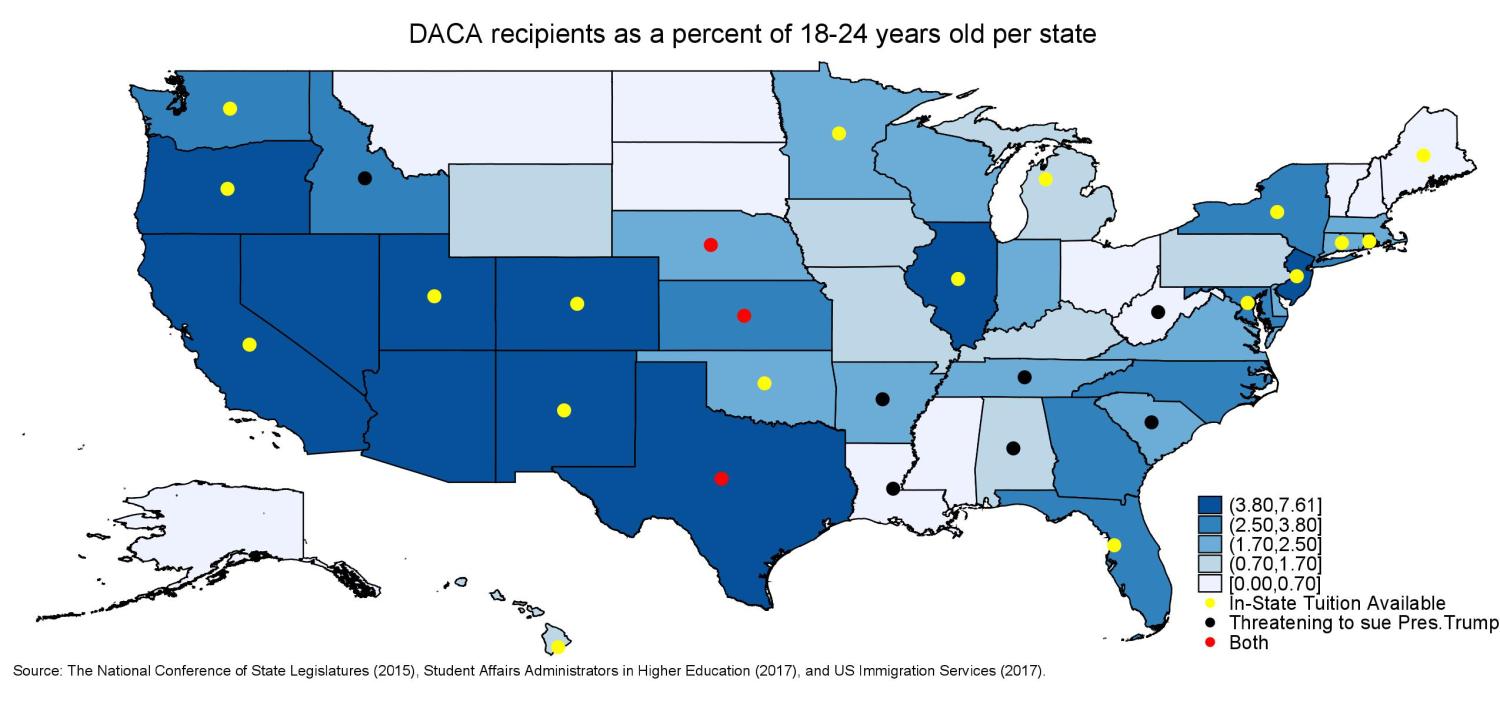

As the map shows, 21 states have either enacted laws that allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition or have university systems that offer in-state tuition to undocumented students. Reacting to the recent threats to DACA, Democratic-led states, in theory, could lead a push to enact additional in-state tuition laws. Indeed, a coalition of 20 Democratic state attorneys general sent a letter urging Trump to keep DACA. It is worth noting that six states without in-state tuition laws—Delaware, Louisiana, Montana, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—currently have Democratic governors. Out of these, four states’ attorneys general signed onto the letter supporting DACA: Delaware, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Although DACA recipients in these four states constitute a small percentage of each state’s 18-24 year olds, as mentioned above, a threat to DACA could potentially motivate Democratic governors to pursue in-state tuition laws. Politically, there is strong support for DACA among Democrats: A March poll of registered voters indicates that 84 percent of Democrats support protecting the DACA population from deportation.

On the other hand, if Trump does not rescind DACA, Republican-led states may opt to take matters into their own hands by restricting access to higher education for undocumented students. However, the prospects for state-level policy change on this issue are unclear. Of the 10 states whose attorneys general recently demanded that Trump rescind DACA, South Carolina and Alabama already have laws blocking undocumented students from receiving in-state tuition. In contrast, three of these states—Texas, Nebraska, and Kansas—offer in-state tuition for undocumented students, and a recent attempt to repeal this in-state tuition law in Texas failed.

The remaining five states in the coalition–Idaho, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and West Virginia–do not have laws that bar undocumented students from access to in-state tuition. Should Trump fail to meet the demands of their attorneys general, it is possible that governors of these states—all of which have Republican legislatures—may pursue such legislation. (This may be the least likely in Louisiana, which has a Democratic governor.)

In this context, whether the political willpower is strong enough for Republican governors to take action remains to be seen. As the map above shows, in each of these five states, DACA recipients are a small share of the population that is roughly of college-going age (18-24); practically speaking, this program does not have a large impact in these states. Further, DACA is not just popular among Democrats. According to the aforementioned poll, a relatively large share of Republicans, 40 percent, support protecting Dreamers from deportation.

Ultimately, with little federal action likely in the near future, the consequences of the letter sent to Trump by the Texas-led coalition are as of yet unclear. States could take action, but this might look very different in states with Democratic and Republican leadership. The threat to DACA could motivate Democratic governors to take steps that would increase access to higher education for students. On the other hand, Republican governors could take steps to restrict access to higher education for Dreamers. However, doing so may be politically risky given the support among both Democrats and Republicans for protecting the Dreamers from deportation.

Caitlin Dermody contributed to this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

With DACA’s uncertain future, how will states address access to higher education?

August 23, 2017