In this super-election year 2024, one key election to watch is the European Parliament election. From June 6-9, around 360 million eligible voters across the 27 European Union (EU) member states will elect representatives to the European Parliament. The past five years have been a turbulent time for Europeans, from the global pandemic and subsequent economic slowdowns to an energy crisis and a reckoning on defense and security precipitated by the first major land war in Europe since World War II. The latest polling suggests that the outcome of the June election will produce strong results for far-right parties, with major policy implications for the EU and its partners around the globe, including the United States.

How do European Parliament elections work?

The European Parliament, together with the Council of the EU (which represents the governments of the EU’s member states), constitutes the EU’s legislative body. It has the authority to review, revise, and vote on legislation, endowing it with significant influence on the European policy agenda. Among the various EU institutions, the parliament is the union’s core democratic pillar as the only institution directly chosen by EU citizens. Strong voter turnout in the election is therefore key to the popular legitimacy and democratic nature of the European policy process. Following each legislative cycle, the parliament also has the role of confirming—or rejecting—a new EU Commission and commission president, the bloc’s executive, as proposed by the European Council (the EU’s top policy-setting institution, which brings together the heads of government of the member states, the president of the Council of the EU, and the president of the commission).

Since 1979, European parliamentary elections have taken place every five years. Voters elect national party candidates in their respective countries, who become part of a European parliamentary group as Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) at the supra-national level. The European groupings mirror the national-level party structures:

- The European People’s Party (EPP) on the center-right.

- The Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) on the center-left.

- The Liberals (Renew Europe) between the center and the center left.

- The Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) toward the left of the political spectrum.

- The European Left on the far left.

- The European Conservatives and Reformers (ECR) on the conservative end.

- The Identity and Democracy (ID) Group on the far right.

- Non-aligned parties.

The number of MEPs for each member state is allocated based on population size, though there is a non-proportional factor favoring smaller member states, which means the population-to-seat ratio is much higher for larger states than smaller ones. (One German seat, for instance, represents almost 880,000 Germans whereas one Estonian seat represents only about 195,000 Estonians.) National parties receive seats in the European Parliament through a system of proportional representation, whose MEPs in turn become part of the European party groupings.

Through the Spitzenkandidat (German for “top candidate”) system, first used in 2014, European party groups also nominate a candidate for the commission presidency to personify their platforms and make the selection process for the EU’s chief executive more transparent. Nonetheless, there is no legal requirement for one of the Spitzenkandidaten to become the new commission president, which means the post could ultimately be filled by a different candidate. Like the U.S. presidential election, the Spitzenkandidaten also participate in public debates—the “Eurovision Debates”—to advocate for their parties’ policies and compete for voter support.

What issues are voters concerned about?

Even though European Parliament elections help determine the EU’s future policy direction, voters are fundamentally driven by issues that affect their daily lives, which inevitably include national-level concerns. Each member state’s election result should thus be viewed as a referendum on both the EU itself and its national government. In a recent Europe-wide survey ahead of the June election, Europeans overall indicated as their top priorities poverty and social exclusion, public health, economic support and job creation, as well as security and defense. Other top issues of concern were climate action, the EU’s future, and migration and asylum policy. All these issues have both a European and a national dimension, which have become increasingly intertwined.

In the past, European voters have used their votes to signal their discontent with local and national policies, due to perceptions that there is a disconnect between the European Parliament and bureaucratic EU processes, and that the parliament lacks relevance relative to other EU institutions. The previous EU election in 2019, however, exhibited the highest voter turnout since 1994 at nearly 51%, with climate change particularly mobilizing younger voters to participate. The 2024 Eurobarometer survey similarly shows that 60% of Europeans are “very” or “somewhat interested” in the election, with 71% indicating that they would be “likely” to vote if the election took place next week. Voters also demonstrated an appreciation for the EU’s role in their daily lives and on the world stage, as well as support for more EU engagement on matters of defense and security, energy resources and infrastructure, and food security and agriculture.

The European Parliament’s current and future composition

Since the last election in 2019, the European Parliament has been governed by a coalition of the center-right EPP, the center-left S&D, and the Liberals of Renew Europe with a combined majority of almost 60%. As the largest parliamentary grouping, the EPP had the prerogative of nominating their Spitzenkandidat, Manfred Weber, for the commission presidency, but he failed to reach a majority for his confirmation. The EPP thus proposed Ursula von der Leyen, who was able to gather greater support and become the EU’s new chief executive.

In terms of the parliament’s political composition, the 2019 vote produced the largest gains for the far-right ECR and ID groupings to date. Together, they have occupied close to 18% of seats as part of the parliamentary opposition, thus increasing their capacity to shape EU policy debates. This has been particularly evident on issues such as migration and asylum policy as well as climate regulation. Nonetheless, there are noteworthy differences between the far-right parliamentary groups, particularly on foreign policy issues such as EU policy toward Russia, China, and the trans-Atlantic relationship. These differences will play a greater role given a probable shift toward the political right after the 2024 election.

Indeed, the latest polling indicates that the June election will result in even greater gains for European far-right parties, with analysts predicting they could occupy between 20-25% of parliamentary seats. Such a result implies a smaller centrist coalition governing the EU, making EU leadership more unstable and susceptible to right-wing influence. Von der Leyen, the current commission president who is running as the Spitzenkandidat for the EPP, has even indicated her willingness to break the firewall to the far-right and collaborate with the ECR—which includes parties such as Poland’s nationalist Law and Justice (PiS) and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s post-fascist Brothers of Italy—to form a governing majority. Von der Leyen is running for another five years as the EU chief executive, yet the prospect of right-wing gains has cast doubt on whether she would be confirmed by a more right-leaning parliament or whether a more conservative candidate may be needed to attain a majority.

Why the European Parliament election matters to the United States

Democracy and the rule of law. The European Union and its individual member states are the United States’ most important partners in defending the international order, characterized by liberal democratic institutions and processes, the rule of law, protection of fundamental rights, and international cooperation through multilateral fora. Particularly in this time of heightened geopolitical tensions, renewed great power competition, and authoritarian threats (internal and external) against democracy, it is of strategic value for the United States to have like-minded partners in the European Union—the parliament and the commission—who are committed to these values at home and abroad.

Defense and security. The United States and the European Union are also deeply interconnected in the realm of defense and security: 23 of the 27 EU member states are formal U.S. allies within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—the largest security alliance in the world. In Article 5 of NATO’s founding treaty, member states have pledged to come to one another’s defense in the case of an attack. This collective deterrence principle has prevented territorial wars in NATO countries since the alliance’s founding in 1949. The trans-Atlantic allies have also been strong partners in providing support to Ukraine in response to Russia’s brutal and illegal full-scale war, with EU institutions and individual member states contributing military, financial, and humanitarian aid, including care for millions of Ukrainian refugees who have fled to Europe. Having European partners who share U.S. assessments of security threats in the North Atlantic theater and are committed to investing in their national defenses to strengthen the alliance is thus relevant to the United States’ own security and defense posture.

Moreover, covert Russian influence operations targeting the European ECR and ID groups and some national far-right parties’ open friendliness toward the Kremlin not only imperil European security but also that of the United States and trans-Atlantic community. Notably, von der Leyen has announced the establishment of an EU defense commissioner to enhance Europe’s defense industrial capacity and coordinate defense matters across member states, should she be reelected as the commission’s president. This intra-European defense coordination would complement—not substitute—NATO and serve to strengthen the European pillar in the alliance.

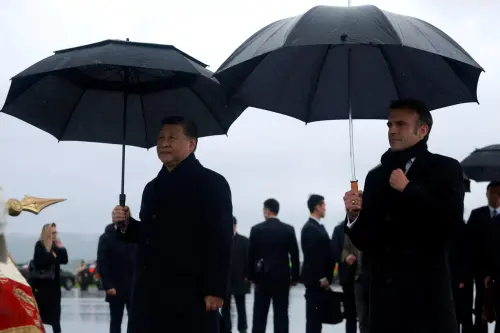

Economics and trade. As the world’s largest single market and free trade area, the European Union is also the United States’ most important commercial partner in terms of trade in goods and services as well as foreign affiliate sales and investment streams. The EU’s economic power also makes it an influential player in U.S. strategy toward China, as Europe navigates questions of economic security and interdependence. In 2019, the EU officially defined China as a “partner for cooperation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival,” yet it has preserved space for closer ties than American policy permits in areas such as trade, investment, and climate. Finally, the European Union—as a community of like-minded liberal democracies—is a critical partner in developing global governance structures for technology and artificial intelligence, energy and natural resources, and climate change.

President of the European Commission. Over the past five years, von der Leyen has transformed the role of commission president, becoming an EU interlocutor to world leaders in her own right, whereas previously the European Council was seen as the power center of the union. Von der Leyen has de facto expanded the commission’s policy reach through her leadership on public health matters in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as on defense and security following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In the process, the EU became a more autonomous and resilient international player and von der Leyen established herself as a respected U.S. partner in matters of transnational governance; on trade issues, however, the relationship has been much more difficult. Von der Leyen was also criticized by some in Europe for being too close to the United States and not sufficiently prioritizing European interests. Yet having won EPP backing and amid attacks on the European Union’s values and unity from authoritarian regimes in Russia and China as well as illiberal forces within Europe, she now hopes to defend and deepen her legacy in another five-year term. Whether she is able to do that will depend on the inroads the hard right makes in the upcoming elections.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why should Americans care about the European Parliament election?

May 17, 2024