This is an update to a November 2023 analysis, which is archived here.

Recently, mortgage rates have reversed some of their increase since 2020, coming down from their recent peak in late 2023. In this piece, we update previous analyses to explore what factors led to the increase through 2023 and what has led to the partial reversal. Overall, the increase in mortgage rates since 2020 reflects a broad increase in rates on long-term U.S. Treasury securities. But the increase in 30-year fixed mortgage rates, particularly from early 2022 through late 2023, has been unusually large relative to rates on long-term Treasury securities, which may suggest that mortgage rates are being pushed up by more temporary factors. Looking at the most recent data, we find that some of those temporary factors are unwinding. If those factors continue to unwind and long-term Treasury rates continue to decline, mortgage rates would also see further declines.

In our previous piece, we investigated why mortgage rates through late 2023 rose so much more than yields on 10-year Treasury bonds. We found that roughly half of the increase in this spread could be attributed to two factors: Interest rates on Treasury bonds with maturities of less than 10 years were higher than rates on 10-year Treasury bonds, and mortgage prepayment risk had increased. The remainder of the increase in the spread was attributed to other factors, such as reduced demand for financial instruments backed by mortgages.

Some of these factors that pushed up the spread have waned. Unlike in late 2023, 10-year Treasury bonds now have higher interest rates than 7-year bonds, which are closer in duration to how long mortgages are typically held. In addition, prepayment risk appears to have come down because of some reduction in uncertainty around future interest rates. The waning of those factors has been partly offset by one factor that has pushed up the spread more in recent months: an increase in the premium lenders are charging borrowers over the rate those lenders are effectively paying for the cost of those funds. That premium might reflect pricing power due to an increase in demand for lenders’ services and increased risk faced by lenders that interest rates will fall over the course of underwriting.

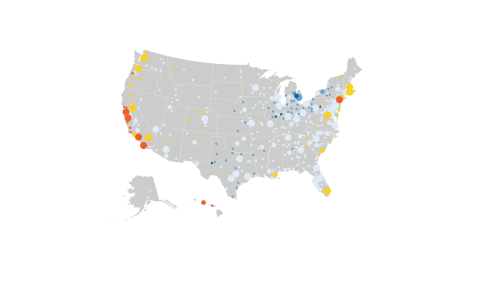

Factors contributing to the spread between mortgage and 10-year Treasury bond rates

Mortgage rates reflect the cost of using a mortgage to buy a home or tap home equity and thus affect the price of real estate and housing wealth. To the degree that the Federal Reserve’s tightening of monetary policy pushed up mortgage rates, this channel is an important way in which tighter monetary policy slows the economy and dampens inflation. As shown in figure 1, there has been a long downward trend in mortgage rates (dark green) over the past 40 years in line with the rate of 10-year Treasury bonds (light green). However, the spread between mortgage rates and Treasury bond rates fluctuates for various reasons, including changes in credit conditions and interest rate uncertainty.

Mortgage rates generally track the rate on 10-year Treasury bonds because both instruments are long term and because mortgages have relatively stable risk. Nonetheless, to compensate investors for the higher risk of mortgages, rates for fixed mortgages have historically been, on average, one to two percentage points higher than Treasury yields. As rates on 10-year Treasury bonds have risen since mid-2020, mortgage rates have risen as well. As discussed in our previous piece, from early 2022 through 2023, mortgage rates rose by a surprisingly large amount relative to the 10-year Treasury rates, putting more restraint on borrowing conditions and the housing market. However, over the past year, the difference between the two rates has shrunk.

Figure 2 shows the spread between 30-year fixed mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury rates from January 1997 through September 2024. The peak spread during the housing crisis was 2.9 percentage points, reflecting a sharp tightening of credit conditions and significant disruptions in the financial markets that fund mortgages. The spread rose again during the COVID-19 pandemic, peaking in 2020 at 2.7 percentage points, reflecting shorter-lived disruptions in financial markets and concerns among lenders and investors in mortgage assets. In late 2022 through 2023, the difference between 30-year fixed mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury rates widened to an unusual degree, hovering near the levels last seen during the housing crisis. In the past year, however, the spread has begun to decrease, and, in September, the spread was lower than the peak level during the pandemic, though still elevated relative to longer-term trends.

To better understand the spread between 30-year fixed mortgage rates and 10-year Treasury rates, figure 3 parses it into three components:

- Blue: The spread between the rate charged to borrowers and the yield on mortgage-backed securities (MBS), referred to as the primary-secondary spread, which is generally stable when the costs of mortgage issuance are stable.

- Light green: A combination of an adjustment for mortgage duration and prepayment risk. The duration adjustment reflects that mortgages are generally held for fewer than 10 years and are more closely related to rates on a 7-year rather than a 10-year Treasury security. Prepayment risk reflects the probability that a future drop in rates induces borrowers to exercise their option to refinance.

- Purple: The remaining spread, which reflects changes in demand for mortgage-related assets after adjusting for prepayment risk.

Given estimates of 1 and 3, we are able to estimate 2 by subtraction.

Understanding recent mortgage rates

Using this framework, we find that the duration adjustment and prepayment risk are now doing less than in late 2023 to push up the spread between mortgage rates and the 10-year Treasury rate. Since mortgages are typically held for fewer than 10 years, they have a shorter duration than 10-year Treasuries. From early 2022 through 2023, and for the first time since 2000, the rate on 7-year Treasury securities was higher than the rate on 10-year Treasury securities. In recent months, this has reversed, and the 10-year rate has been higher than the 7-year (consistent with pre-pandemic trends).

In addition, because of a reduction in interest rate uncertainty, prepayment risk is modestly lower now than in late 2023. Borrowers with mortgages are affected differently if interest rates rise or fall. If rates rise, mortgage borrowers can simply choose to keep their mortgages at the previously issued rate. Instead, if rates fall, mortgage borrowers can prepay and refinance their mortgages at lower rates. That means that if there is a wider range of uncertainty around the future of interest rates—even if that range is symmetrical—there is a higher probability that current mortgage borrowers will find it advantageous to refinance in the future. As it happens, measures of interest rate uncertainty (such as the MOVE Index, or Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate Index) are currently lower than in late 2023.

Partly offsetting the effects of prepayment risk and duration adjustment is an increase in the primary-secondary spread since our previous analysis. Lenders often finance mortgages by selling claims to MBS, which are pools of mortgage loans that are guaranteed by government-sponsored enterprises. The spread between the primary mortgage rate to borrowers and the secondary rate on MBS reflects the costs of issuing mortgages and the pricing power lenders have given borrower demand. Both have likely increased. First, an increase in demand among mortgage borrowers has given lenders more pricing power. Second, originators have to bear interest rate risk between the time an interest rate on a mortgage is set and when it is closed. In an environment when mortgage rates are falling and expected to continue to fall, lenders face greater risk that borrowers will renegotiate to borrow at lower rates.

The last component, which is left after accounting for those factors described above, is the option-adjusted spread (OAS; “other” in figure 3) which has also declined since late 2023. Exactly why that factor is smaller is uncertain, but this pattern is seen across fixed income assets. For example, the spread between highly rated corporate bonds and the 10-year Treasury rate has diminished since the end of 2023.

Conclusion

On September 18, the Fed cut short-term interest rates by half a percentage point and is expected to cut rates further. If those developments (and others) continue to drive down long-term Treasury rates, mortgage rates are likely to continue to fall. In addition, if interest rate uncertainty diminishes, the spread between mortgage rates and the 10-year Treasury rate should return back toward historical levels, further reducing rates. Those lower rates will make borrowing cheaper for potential mortgage borrowers—including those looking to borrow against home equity and those looking to purchase a home. We caution that such a reduction in mortgage rates will not be enough to make housing broadly affordable, which will take increases in the supply of affordable housing for both homeowners and renters.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful to Laurie Goodman for helpful comments on this work and to Lauren Bauer, Aaron Klein, David Wessel, and Paul Willen for their insightful comments on previous analyses.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).