Four years after the COVID-19 pandemic, its consequences are still palpable in school attendance and enrollment. While in 2022-23 the share of students attending traditional public schools (TPS) increased by roughly 1 percentage point relative to the prior year, it remains 4 percentage points below 2019-20. These enrollment losses are not fully explained by population changes or changes in charter school enrollment. In this post, we consider the reasons families may explore schooling options for their children away from TPS and discuss their implications. We use family satisfaction data from New York City Public Schools to assess the role of perceived school quality in school enrollment decisions. Insights from targeted interviews of home-educators and professionals supporting families pursuing non-classroom-based learning help us delineate what student experience may look like in the changing K-12 education landscape.

Changing landscape of school enrollment

The enrollment declines after COVID-19 reflect a changing K-12 education landscape. The pandemic has been a wake-up call for many families. COVID-19 gave parents and guardians a window into what was happening in their kids’ classrooms and forced them to explore alternative learning arrangements, which included teaching their children at home. This helped them find out how easy or difficult it is to teach their children as well as whether their pre-pandemic schooling arrangements did a good job educating them. This realization has pushed families to consider different schooling arrangements after COVID-19. The incentives of families to explore different schooling arrangements might have been even greater when families felt that the TPS system could not deliver a high enough pace of learning for their children. This could represent families of children on both ends of the performance distribution. Families of children who may be struggling at school—including those who experienced learning losses during the pandemic—are likely to try out something new to help their child catch up.

Families of higher-performing children may also be willing to explore new arrangements. The families of these students often feel that the traditional public school does not allow them to learn fast enough, possibly because the pandemic-induced learning resulted in academic gains for these students. In either case, the combination of pandemic-induced realizations about school performance and availability of arrangements that promise accelerated learning has led parents to want to check if the grass is greener on the other side of TPS. At the same time, any alternative arrangement that families tried out during the pandemic may have stuck post-COVID-19, possibly because these arrangements work well enough for families not to change them.

Perceived school quality

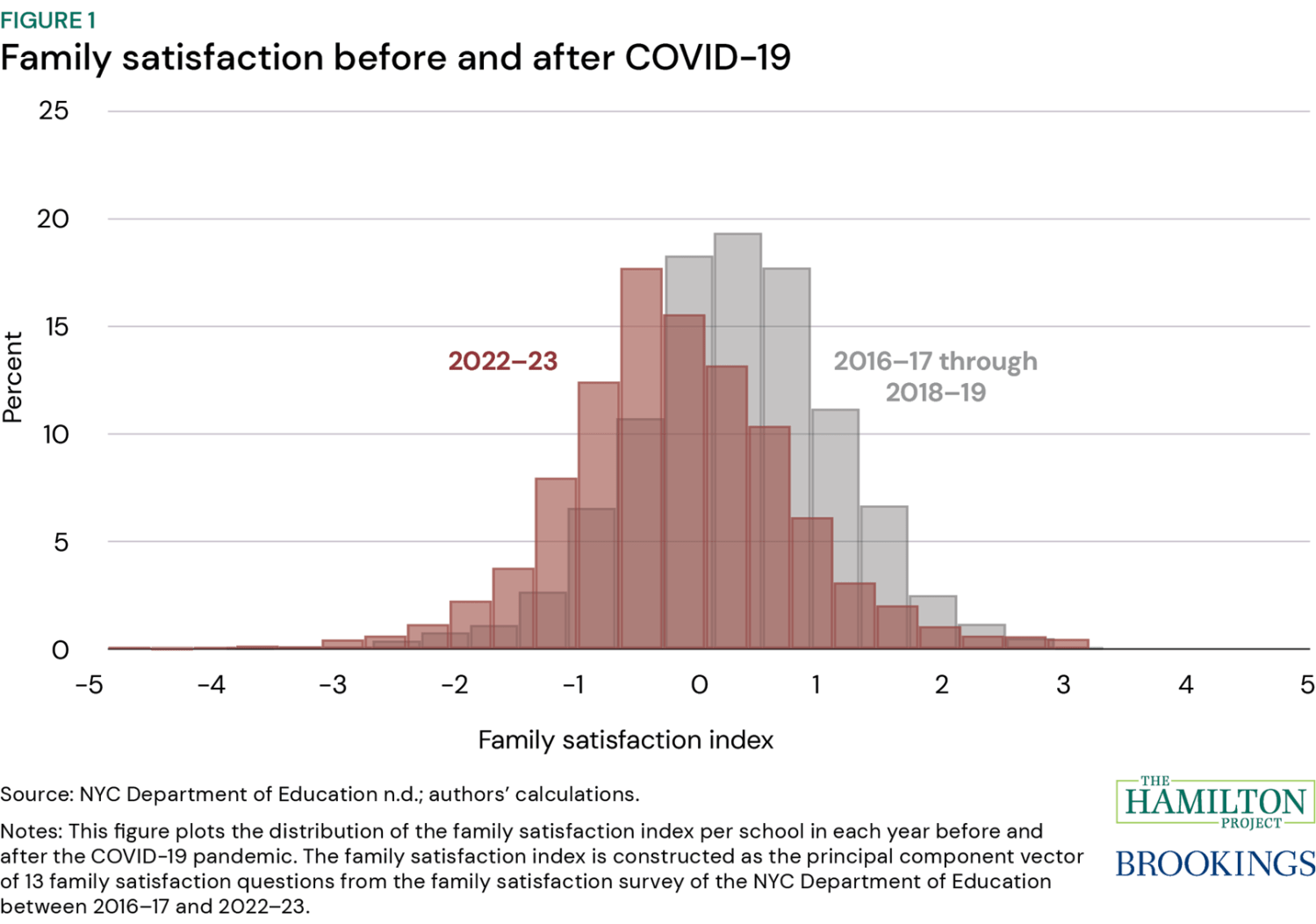

We use data on family satisfaction from the annual New York City School Survey administered to parents and guardians to investigate changes in family satisfaction regarding school quality before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, which may be a driver of willingness to consider alternative arrangements. We construct an index of family satisfaction using 13 questions related to satisfaction with the education their child receives at school, whether they report being satisfied with their child’s teachers, and whether they believe the school provides resources for and prepares their child for college, career, and success in life.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the family satisfaction index across schools during the three years prior to the start of COVID-19 (school years 2016-17, 2017-18, and 2018-19) and 2022-23. The results show a negative shift in family satisfaction after COVID-19.1 In particular, more families reported lower levels of satisfaction from school quality after COVID-19 relative to before COVID-19.

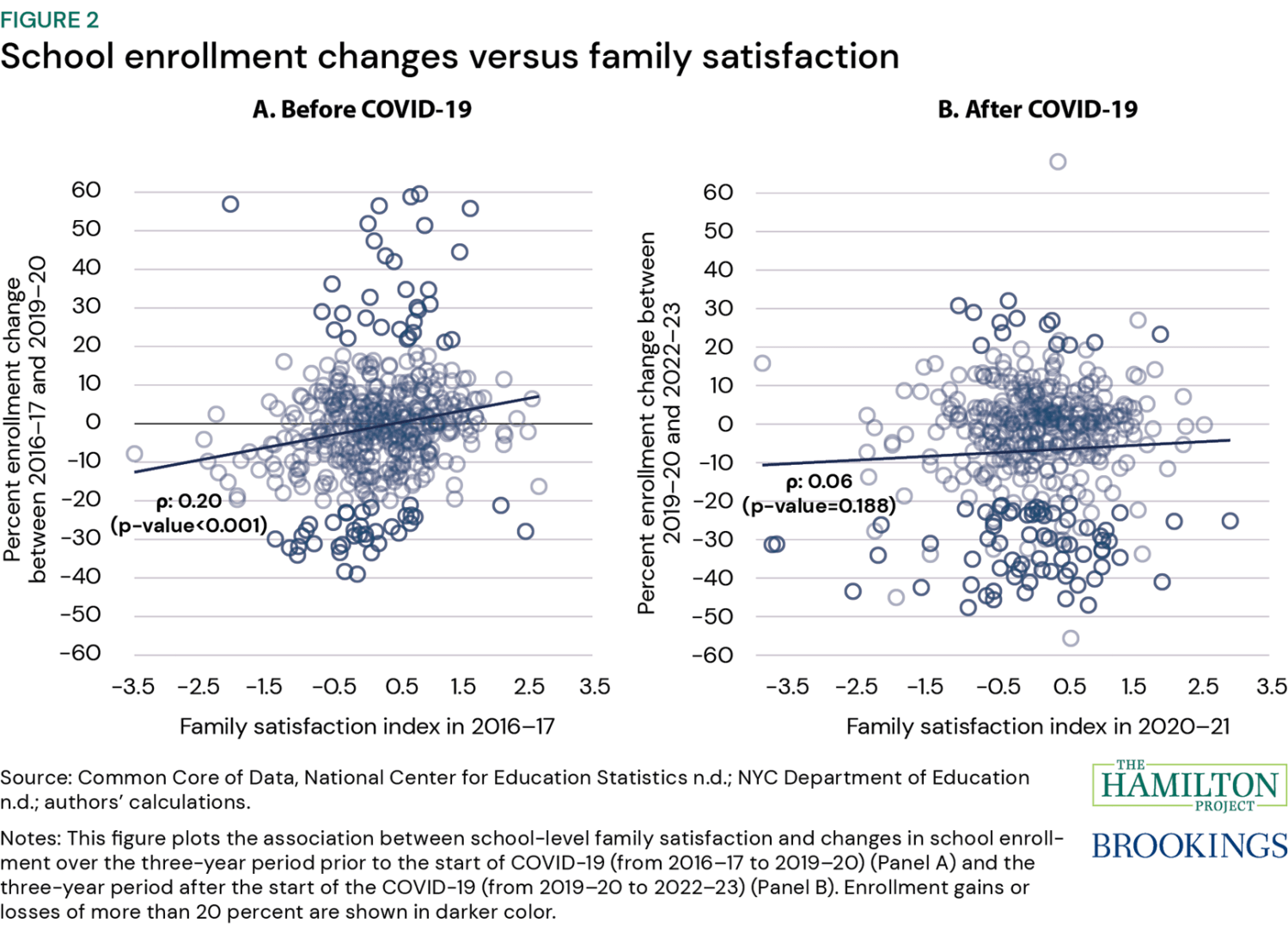

Family dissatisfaction with public schools’ response to COVID-19 may be associated with public school disenrollment. Figure 2 explores the school-level association between family satisfaction and enrollment changes before and after COVID-19 in NYC. Dissatisfied families who leave public schools are not included in this investigation. Panel A of figure 2 shows the scatterplot, along with a fitted line, and a correlation coefficient between family satisfaction and the change in school enrollment over a three-year period before COVID-19. Panel B of figure 2 shows the association between family satisfaction and the change in school enrollment over a three-year period after COVID-19. The results reveal a decrease in the association between family satisfaction and school enrollment after COVID-19.2 This suggests that as family satisfaction becomes more complicated after COVID-19 (i.e., the distribution widens as variance increases), other factors may contribute to family decisions regarding school enrollment.

Demand for learning flexibility after COVID-19

The types of learning arrangements away from TPS that many families have considered since COVID-19 vary. Families have explored options like charter schools, private schools, and home education. A previous THP paper showed that neither population changes nor changes in charter school enrollment since 2020 fully explain the enrollment losses of TPS. Neither does the increase in private school enrollment explain away the declined enrollment of TPS. This suggests that many families may have chosen to educate their children at home after COVID-19.

In 2019, about 3.7 percent of students ages 5–17 received instruction at home. Interest in homeschooling grew rapidly during the pandemic with 11.1 percent of households with school-age children homeschooling in Fall 2020. Data from 390 districts show at least one home-schooled child for every 10 in public schools during the 2021-22 school year. No nationwide data on home education have been made available after the pandemic.

The choice of families to educate their children at home may be related to a family’s educational level and their capacity to allocate time to home education. The proliferation of flexible working arrangements after COVID-19 also may have allowed families to explore learning arrangements for their children that were previously less attainable for households with working parents/guardians.

The reasons families educate their children at home after the pandemic may differ from families that home-schooled their children before COVID-19. The nature of the home-schooling experience and the families’ expectations in terms of results may also differ. The lack of current nationwide data on home education after COVID-19 and the wide variation in reporting requirements of home education across states makes it difficult to grasp the prevalence of homeschooling and what homeschooling looks like today. To understand better what home education means after COVID-19, we spoke with home-educators and professionals who help families educate their children primarily at home. We present here what we learned.

Families’ motivations for home education are different after COVID-19 relative to prior the pandemic, our interviewees explained. Before COVID-19, most families educating their children at home were doing so due to ideological, moral, or religious reasons. According to 2019 data from the National Household Education Survey (NHES), 74.7 percent of families reported their motivation for home-schooling as “a desire to provide moral instruction.” Similarly, 58.9 percent of respondents reported “A desire to provide religious instruction” as a reason for homeschooling. In contrast, our targeted interviews suggest that families taking their children away from the TPS system in recent years are more likely to be motivated by a desire to improve their child’s pace of learning or provide more specialized learning.

Because families’ motivation for home education differed prior to COVID-19, the content families choose to teach their children after COVID-19 is different from before. Our interviewees report that after COVID-19, parents and guardians are less likely to deviate from standard school curriculum compared to families that home-schooled before COVID-19. Three factors support this practice. First, the reason that some families home-school after COVID-19 is precisely because their child struggled with the content taught at school. As a result, this content is the first thing the families try to tackle before considering other material. Second, parents and guardians are often not professional educators, and they are more likely to teach material for which study guides, textbooks, and curricula already exist. Third, families who are new to home-schooling are often uncertain whether this arrangement will work well for their child or whether they will be able to maintain this arrangement long-term, and they want their child to be able to re-integrate back into the TPS system. Home-schooled children who are taught standard school content may have an easier time re-joining a classroom-based instructional model.

Home-based schooling arrangements are not as isolating as one may imagine, our interviews suggested. For example, some families often arrange for a hired teacher to teach a small number of children in the neighborhood. Or some parents and guardians, while primarily teaching their children alone at home, may plan social and learning activities with groups of other home-schooled students.

An interviewee reported that charter schools that provide non-classroom-based learning or independent study, which have gained students post-COVID-19, allow families to pursue home education while still being connected online to a system that provides support to the children and their families. Families that choose to enroll in one of these non-classroom-based charters are assigned a teacher for their child and are provided with a budget for educational resources their student may need. The teacher assigned to the student will routinely evaluate the learning progress of students at home, ensuring that they are still meeting state or local required educational standards. Non-classroom-based charter schools are more common in Alaska and California.

Homeschooling regulations vary widely across the US. While it’s legal in all 50 states, tracking and oversight differ. Some states do not require families to notify school officials, while others require an official notice once or annually. Requirements vary for parent qualifications, assessments, subjects taught, and immunizations. Access to special education and extracurriculars also varies. To the extent that staying connected to a school while home educating can be part of regulatory requirements, non-classroom-based charter schools offer a legal vehicle for home education.

The connection with a school is important to many families who are new to homeschooling or to students who need learning support services or those who plan to later return to more traditional schooling options. Some families report non-classroom-based schools working well for their young elementary-aged children and their middle school children but describe their high-school aged child to have a desire for things a non-classroom-based schools are not usually able to provide, such as clubs or sports teams.

Public charter schools that allow for students to learn primarily at home also open a window for families who wanted to try home-schooling but felt that it was financially inaccessible, our interviewees suggested. The cost of books, lesson plans, and learning materials can add up. The financial strain of those resources often impacts families’ decision to homeschool. Through non-classroom-based charter schools, the financial burden of home education shifts from the individual household as these students receive similar funding to those enrolled in classroom-based public schools.

Implications

Families’ demand for flexibility regarding schooling arrangements and pedagogical approaches is higher after COVID-19 relative to pre-pandemic. The motivations of families for taking their children out of traditional public schools might have changed post-pandemic. After COVID-19, many families feel that what public schools offered before COVID-19 is not enough now. We believe this helps explain the enrollment declines we see in TPS.

Of course, preferred school arrangements outside the TPS system look different from household to household, and some of these arrangements likely existed even before COVID-19. In some of these learning arrangements, such as the home-based ones, it is hard to know whether students learn at a faster pace than they would in TPS. In many states, standardized testing is optional, while colleges and universities often waive the test score requirement in admission applications. This means that student performance data availability is limited but also the data available may be skewed toward test takers who are more likely to do well as they can use their scores to improve signaling in their college applications.

A key implication of our investigation is that more data are needed to understand the demand for more flexible or personalized learning arrangements after the COVID-19 pandemic and the learning efficacy of these arrangements. Particularly, data on how many students flow toward non-classroom-based learning arrangements, what are the demographics of these families, and what are the demographics of those left behind are much needed to understand the equity implications of declined enrollments. From a planning perspective, more complete and accurate measurement is needed to design policies and programs that help students learn, regardless of where they learn.

Declining enrollment in brick-and-mortar schools may mean that eventually fewer of them are needed. School closure or consolidation is likely to adversely affect families who do not have access to learning arrangements away from TPS. Without knowing how permanent the new equilibrium of the K-12 education landscape is, one may worry that lost school infrastructure and decreased capacity in student seats will hurt those who will rely on TPS in the future.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- Results are similar when data from the 2020-21 school year or the 2021-22 school year are used.

- The results are similar when the family satisfaction index in 2019-20 is used instead of the family satisfaction index in 2020-21 in the investigation of the association between family satisfaction and school enrollment changes after COVID-19.