President-elect Donald Trump’s deal to save the jobs of 730 workers at the Carrier plant in Indiana is a first attempt to deliver on his forceful campaign rhetoric to help workers and communities dislocated by trade. Rather than an unsustainable strategy that cuts deals firm by firm, though, the Trump administration should reform and expand the federal government’s trade adjustment policies to support a much wider swath of trade-displaced workers.

Economic theory acknowledges that global trade offers benefits that should be celebrated and exacts costs that cannot be ignored. As the Council on Foreign Relation’s Edward Alden details in a new book, this reality led to the creation of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) in 1962.

Trade Adjustment Assistance is the country’s signature support program targeted to workers affected by global competition. In fiscal year 2015, about 58,000 workers became eligible for TAA’s benefits and services, which include job training and job-searching assistance. Since its inception, the TAA program has certified nearly 4.9 million workers and served approximately 2.2 million workers.

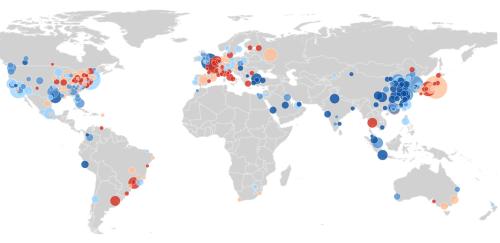

The program’s Consolidated Petitions Database, which has been geocoded and provided online by Public Citizen, offers an estimate of the number of workers at trade-affected companies, including both layoffs and employment reductions through attrition. Analysis of this database, which includes records dating back to 1994, reveals three core findings about the geography of trade dislocation.

Trade adjustment assistance touches nearly every community in the United States, both large cities and outlying areas.

One-half of TAA-certified Americans lives and works in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas (Figure 1). Since 1994, the top 10 metro areas in terms of total TAA-certified workers include the largest metros in the country—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Philadelphia, and Boston. Also in the top 10 are export-intensive midsized metros like Detroit, Charlotte, and Portland. El Paso—on the U.S.–Mexico border—rounds out the top 10. Small metro areas—those with populations between 50,000 and 500,000—house 21 percent of TAA-certified workers while micropolitan areas (those with populations under 50,000 residents with a core city of at least 10,000) and rural areas account for a combined 29 percent of TAA-certified workers.

As a share of the overall employment base, TAA-certified workers are most concentrated in rural and micropolitan areas.

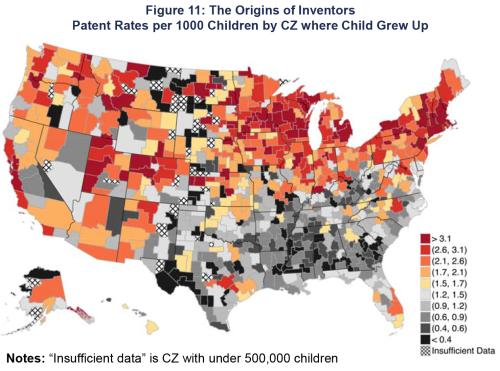

Although those areas of the country constitute a minority of overall TAA-certified workers, the effects of trade are certainly felt most acutely there. Consistent with previous research, the most intense effect of trade displacement is in smaller communities in the Midwest and South (Figure 2). Other high concentrations of displacement cluster in the Carolinas, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and parts of Ohio and Michigan that depend on manufacturing industries that are subject to global competition and technological automation (Map 1).

The areas of the country most affected by trade tended to vote for Trump.

Figure 3 categorizes 868 metropolitan, micropolitan, and rural areas into five groups on the basis of a ratio of TAA-certified workers per 1,000 workers. Approximately 90 percent of the communities most affected by trade voted for Trump, while only 72 percent of those least affected did so. That trade-affected communities leaned toward Trump squares with previous research showing that regional labor markets facing rising import competition pushed voters toward the president-elect.

A comprehensive solution to the economic challenges facing workers and communities that have lost out to trade is beyond the scope of this blog. But this analysis points to a few takeaways that should be considered as policy debates unfold.

First, all communities are home to export industries and, to varying extents, are affected when those industries lose out to global competition. This phenomenon is surely felt most acutely in smaller, outlying communities, but it is a challenge shared by big cities, small towns, and rural areas alike. Yet, closing regions and workers off from global competition is unlikely to be a successful counterstrategy. The most trade-displaced metros still tend to be export-intensive.* Simply raising tariffs or backing out of trade deals could raise the prices of intermediate inputs for existing export industries in these markets, further degrading their global competitiveness and spurring further job loss and economic distress.

Yet business as usual will not suffice. The TAA program, as it is currently deployed, has not been particularly effective in helping displaced workers. Its scale is insufficient relative to the scale of displacement. Indeed, MIT’s David Autor and colleagues find that most displaced workers rely on Social Security and disability benefits rather than the retraining resources provided by TAA.

A new “adjustment agenda” is required that arms these workers and communities with the resources to help them get back on their feet. Reforming the TAA program, and combining it with wage insurance, more comprehensive training assistance, and even resources that help workers move to regions with greater economic opportunities could be part of a broader Trump administration response. We will have more to say about what this response might look like in the coming months. For now, we would just say that getting serious about helping workers dislocated by trade would be a great outcome of the Trump years.

*The correlation between export intensity (the share of metro gross domestic product derived from exports) and TAA-certified workers per 1,000 workers was 0.25 (p < .01).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Where global trade has the biggest impact on workers

December 14, 2016