Religious proselytizing is one of the most important elements of Saudi Arabia’s global soft power strategy. Every year it spends millions—some say billions—of dollars to spread its ultraconservative brand of Islam. But this was not always so. Much of the current form of Saudi proselytizing took shape after 1967, when religious rhetoric filled a vacuum left behind by secular pan-Arab nationalism.

Religious proselytizing is one of the most important elements of Saudi Arabia’s global soft power strategy. Every year it spends millions—some say billions—of dollars to spread its ultraconservative brand of Islam. But this was not always so. Much of the current form of Saudi proselytizing took shape after 1967, when religious rhetoric filled a vacuum left behind by secular pan-Arab nationalism.

During WWII and its immediate aftermath, Saudi Arabia’s founder Abd al-Aziz and his successor Saud spent little to fund proselytizing abroad, preferring instead to spread the creed at home to consolidate their political authority over their recently annexed territories.

It was not until Arab nationalist revolutions swept away several monarchs in the Middle East and North Africa that Saudi Arabia began to proselytize abroad again to stem the rising secular tide. In 1962, Crown Prince Faisal helped establish the Muslim World League (MWL) with the express purpose of spreading Wahhabism to blunt the appeal of Arab nationalism, a mission it continues today. He hoped that by championing Islamic causes abroad, he could persuade conservative Muslim governments and activists to ally themselves with the kingdom rather than with nationalist leaders like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser. Pan-Islamism would be the answer to pan-Arabism.

Initially, the appeals by Crown Prince (and later King) Faisal for pan-Islamic solidarity earned him little more than good wishes from remote Muslim countries and scorn from Arab states who criticized the Saudi monarchs for their chumminess with the United States. But that changed with the 1967 War, after which Saudi calls for Muslim solidarity resonated much more deeply because Muslim opinion around the world was inflamed after the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem, the location of one of Islam’s holiest shrines. Whereas Nasser had used the Marxist language of anti-imperialism to galvanize Arab support for the war, King Faisal used the religious language of jihad to spur Muslims to reverse its aftermath. To that end, he organized a series of conferences and in 1969 founded the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to “support the struggle of the people of Palestine.” Today, the OIC counts 57 nation-states and remains committed to supporting Palestinian self-determination and reviving Islamic culture.

Whereas Nasser had used the Marxist language of anti-imperialism to galvanize Arab support for the war, King Faisal used the religious language of jihad to spur Muslims to reverse its aftermath.

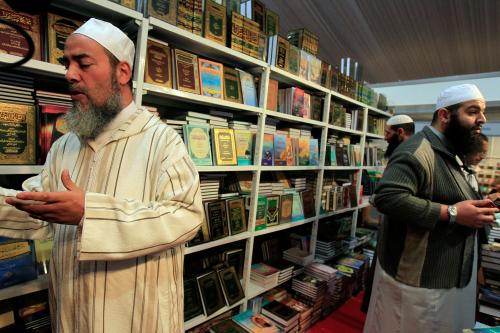

King Faisal also stepped up financial support for religious proselytizing abroad to cement the kingdom’s ties with conservative Muslim governments, to aid Islamist activists pushing their countries in a more conservative direction, and to orient Muslim minorities toward the kingdom. In 1972, he established the World Association of Muslim Youth, charged with coordinating the missionary activities of Muslim youth organizations abroad. Faisal also began building mosques and Islamic centers around the world, extending to West Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Europe, and the United States. His successors have continued to spend lavishly on the project, either directly or through organizations like the MWL.

Saudi Arabia’s promotion of transnational Islamic solidarity not only attracted well-wishers far beyond the kingdom’s borders; it also helped give rise to a generation of Islamist activists who articulated their political grievances in Islamic terms. Beginning a little over a decade after the 1967 war, some of those activists began criticizing and attacking Saudi Arabia itself on Islamic grounds, contending that the kingdom hypocritically championed Islam against an imperial Christian West while relying on the West for its security. Saudi Arabia’s Western allies began to level a similar criticism at the kingdom after 9/11, charging that Saudi proselytizing had nurtured the anti-American sentiment that led to the attacks on the World Trade Center.

Over the past three decades, the rationale for Saudi Arabia’s global proselytizing enterprise has changed. Whereas it was built in the 1960s and 1970s to counter the influence of Arab nationalists, it is sustained and expanded today to counter Iranian Shiite proselytizing. But even though the rationales for exporting the Saudis’ creed abroad have evolved, proselytizing remains a potent weapon in Saudi Arabia’s soft-power arsenal, which means the kingdom is unlikely to abandon it anytime soon.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What the 1967 War meant for Saudi religious exports

May 30, 2017