On August 8, 2018, Joseph Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), announced that he would not participate as a candidate for the presidency in elections scheduled to take place on December 23, 2018. He picked former interior minister, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, who is considered a “hard-core loyalist,” to represent the ruling coalition (Common Front for Congo/Front commun pour le Congo) in the elections. The announcement was seen as extremely important because it ended many years of uncertainty regarding whether or not Kabila would eventually eliminate presidential term limits and remain in power indefinitely. I assess prospects for these elections to restore peace and stability and create hope for the future.

A country with a turbulent and violent history

The DRC gained independence from Belgium on June 30, 1960, under the leadership of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. Shortly after independence, the country was plunged into a political quagmire that was characterized by military mutinies, attempted secession by two provinces, and the eventual military overthrow of the government in 1965 by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who at the time was chief of the Congolese armed forces. Mobutu ruled the country from 1965 to 1997, when he was ousted by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. However, Laurent-Désiré Kabila was assassinated by one of his bodyguards in 2001 and was succeeded a few days later by his son, Joseph Kabila, who remains the president of the DRC to this day.

Joseph Kabila was elected president in 2006 and re-elected in 2011—the late opposition leader, Étienne Tshisekedi, claimed that he had won the 2011 presidential election and international observers adjudged it to have been pervaded with fraud and irregularities. Kabila’s reign has been characterized by high levels of sectarian violence, increased poverty, high levels of corruption, and the increasing use of violence by the government to suppress citizen dissent.

Joseph Kabila and the DRC’s constitutional crisis

When he was elected president of the DRC in 2006 and 2011, Kabila was constitutionally limited to two terms in office—his last term in office was supposed to end at midnight on December 19, 2016. A presidential election was supposed to be held on November 17, 2016, to produce Kabila’s successor. However, the country’s electoral commission, the Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI), postponed the elections, claiming that it had not yet conducted the necessary census to accurately determine the number of voters and that it did not have the more than $1 billion needed to successfully carry out the elections. At the time, many observers, especially members of the opposition, believed that it was actually Kabila and his political supporters who were behind the decision to postpone the elections.

Kabila and the constitutional coup d’état

Since the November 2016 election was postponed, the country’s highest court, the Cour constitutionnelle (CC), was called upon to determine how the vacancy in the presidency was expected to be filled. The CC held that Kabila could stay in power if the country failed to hold elections to select his successor. The opposition, which had expected an interim president to take over, argued that the decision by the CC represented an opportunistic interpretation of the constitution. In addition, many opposition leaders considered the CC’s decision a constitutional coup and argued that Kabila was essentially trying to postpone the elections to stay in power indefinitely.

The question asked by many observers was: Why didn’t the CC allow the president of the Senate to serve as the country’s interim president as mandated by Article 75 of the constitution? Once his constitutional mandate ended on December 19, 2016, Kabila should have been permanently barred from staying in power or competing for the position of president.

The CC, instead, relied on Article 70 of the constitution, which states that “[a]t the end of his term, the President stays in office until the President-Elect effectively assumes his functions.” Article 70 does not make mention of elections to determine a successor—it does not say that the outgoing president should stay in power until elections are held to select his or her successor. Instead, Article 70 pre-supposes the existence of a president-elect and, hence, did not apply to the failure of the DRC to hold elections in November 2016. Since there was no president-elect, the crisis should have been governed by Article 75 and the president of the Senate should have been installed as president of the DRC and his government then charged with the responsibility to conduct elections and choose a permanent president.

In addition to Congolese opposition parties, many international actors, including the African Union, the United States, and the United Nations, have asked Kabila not to seek a third term but to leave office after the December 2018 elections. Recently, the U.S. government, which had imposed sanctions against some of Kabila’s senior officials, threatened to “tighten financial sanctions against Mr. Kabila…if he did not agree to relinquish power.”

What is at stake?

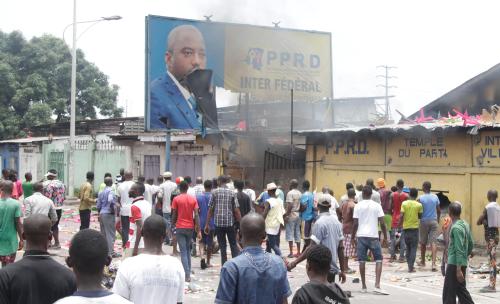

Granted, Kabila has announced his intention not to participate as a candidate. Yet, there are questions about whether a fair, credible, free, and peaceful presidential election will be held or will this simply be a ploy to allow Kabila to remain in control of the government? Despite the fact that there is a lot of pressure for him to leave office, many Congolese are afraid that Kabila will use some excuse, such as the lack of resources and the absence of an official electoral register, to again postpone the elections. Alternatively, some observers are speculating that the choice of a die-hard loyalist, such as Ramazani, could be an indication that Kabila simply wants to have someone who will keep the presidency for him as he will be eligible to return in 2023. In addition to the fact that Kabila will retain his position as leader of the People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie—PPRD), he has also packed the federal bureaucracy, including the courts and the military, with his loyalists.

Nevertheless, Kabila’s decision to leave office at the end of the year should put an end to the constitutional crisis and significantly reduce the probability of another civil war. Whether the temporary peace will become permanent will depend, to a large extent, on (1) the extent to which the 2018 election is considered fair, credible, free and peaceful, especially by the Congolese people; (2) the ability and willingness of the new government to bring the Congolese people together and engage them in robust dialogue about effective reconstruction of the state and the provision of a governing process undergirded by the rule of law; (3) the willingness of the new government to combat impunity and deal with problems such as youth unemployment, lack of infrastructures, and the absence of basic social services, such as education, healthcare, affordable housing, and clean drinking water; and (4) the ability of the new government to guarantee peace and security, including the provision of mechanisms for the peaceful resolution of conflict. Kabila’s absence from the political scene could provide the Congolese people with the opportunity to finally create a governing process that is characterized by true separation of powers with checks and balances, including an independent judiciary.

Regardless of who the next president is, the new government must be one of national unity and designed specifically to build institutions for the future and not to maintain the status quo. Anything short of such an inclusive government will trap the DRC in a state of underdevelopment, characterized by extreme poverty, especially among urban youth, political dysfunction and insecurity, and the failure of the government to effectively and fully manage diversity. Kabila and his government must make sure that the presidential election in December is conducted in a fair, free, peaceful, and credible manner so that it can offer the Congolese people viable options for change. Since the assassination of the country’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961, there has been widespread dissatisfaction among the DRC masses. The next government has the opportunity to radically transform the DRC from a country trapped in political violence, underdevelopment, and extreme poverty to one with plenty of opportunities for self-actualization and a government that is trusted by its citizens.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What is at stake for the DRC presidential election?

August 29, 2018