Cities across the U.S. are aiming to transform their office-dominated downtowns into inclusive hubs for living, working, and playing in the work-from-home era. The mayor of Washington, D.C., Muriel Bowser, has called for the city to add 15,000 residents to the city’s downtown area by 2028. But as she celebrated downtown’s first major residential conversion, commentators spotlighted the steep rents, with studios starting at nearly $3,000 per month.

Economic research has established that density regulations contribute to unaffordability. In response, cities have begun to unravel their outdated building height limits to accommodate new residents and businesses in their downtowns. However, the federal Height of Buildings Act prevents downtown Washington, D.C. from expanding upwards to accommodate growth.

As my recent report finds, the District is the world’s largest metro area by GDP without a skyscraper; the Height Act is the main reason why, with virtually every private lot in downtown already built to the Height Act’s limits. Unmet demand from residents and businesses ‘regulated out’ of downtown has spilled over to nearby neighborhoods, namely Navy Yard, NoMa, and Mount Vernon Triangle. These downtown-adjacent areas have received most of the city’s new development, while the downtown itself has hardly grown. By suppressing the supply of building space in downtown Washington, the Height Act prevents residents and businesses who wish to locate downtown from doing so—and artificially raises real estate values for those who do.

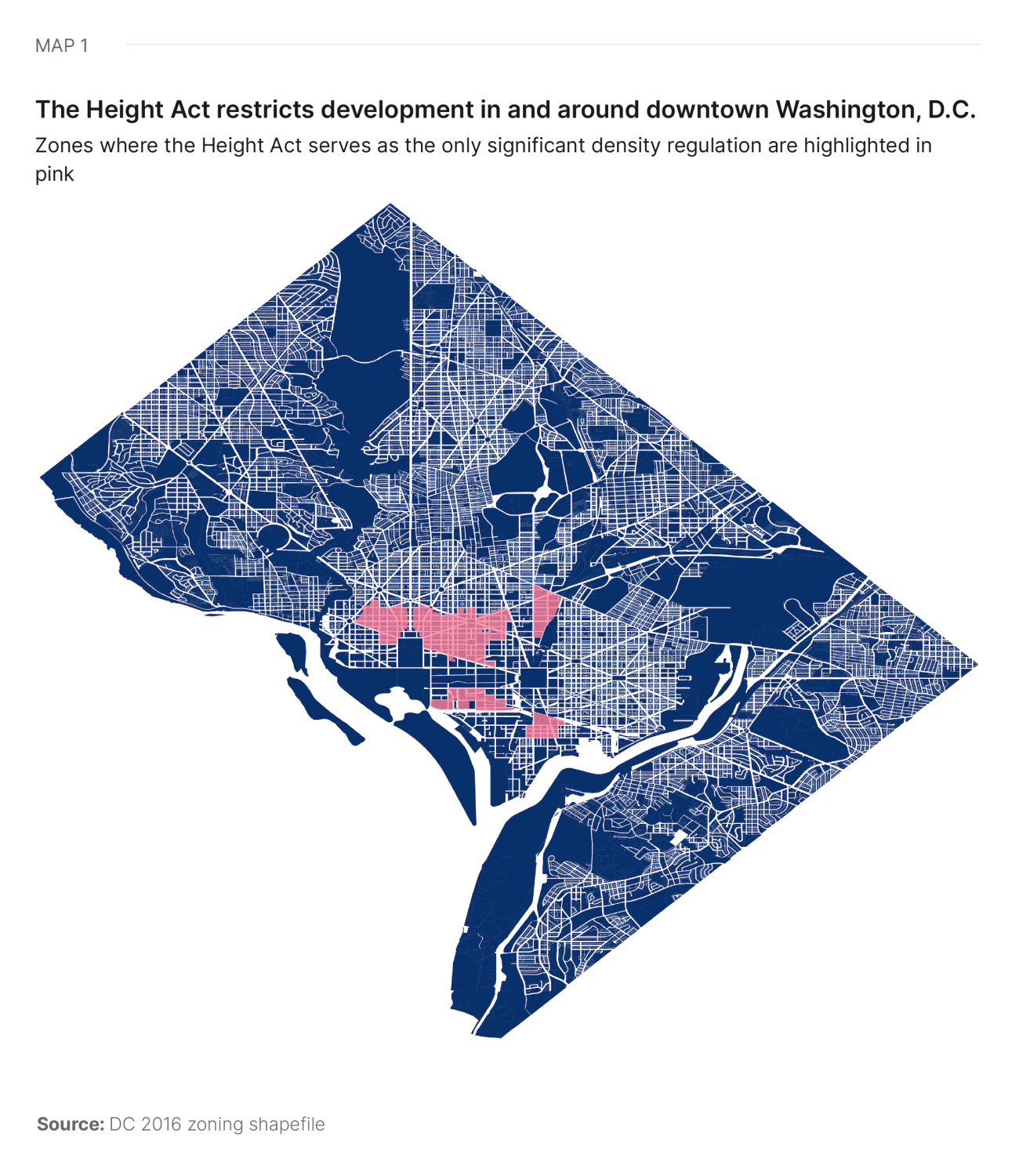

The Height Act is the only significant density regulation in downtown Washington, DC

Passed by Congress in 1910, the Height Act limits building heights to the width of their street plus twenty feet, with a maximum of 130 feet (about 12 stories) on commercial streets. Contrary to urban legend, the height limit is not tied to the Washington Monument or the Capitol Building—these structures are far taller than the Height Act allows.

Though the Height Act applies city-wide, it only restricts building heights in central Washington, D.C. Elsewhere, the District’s zoning code imposes even lower building height limits and/or constrains building size through floor area ratio (FAR) restrictions. But buildings can reach the Height Act limits without FAR restrictions in central parts of the District (highlighted in Map 1), making it the only significant density restriction in and around downtown.

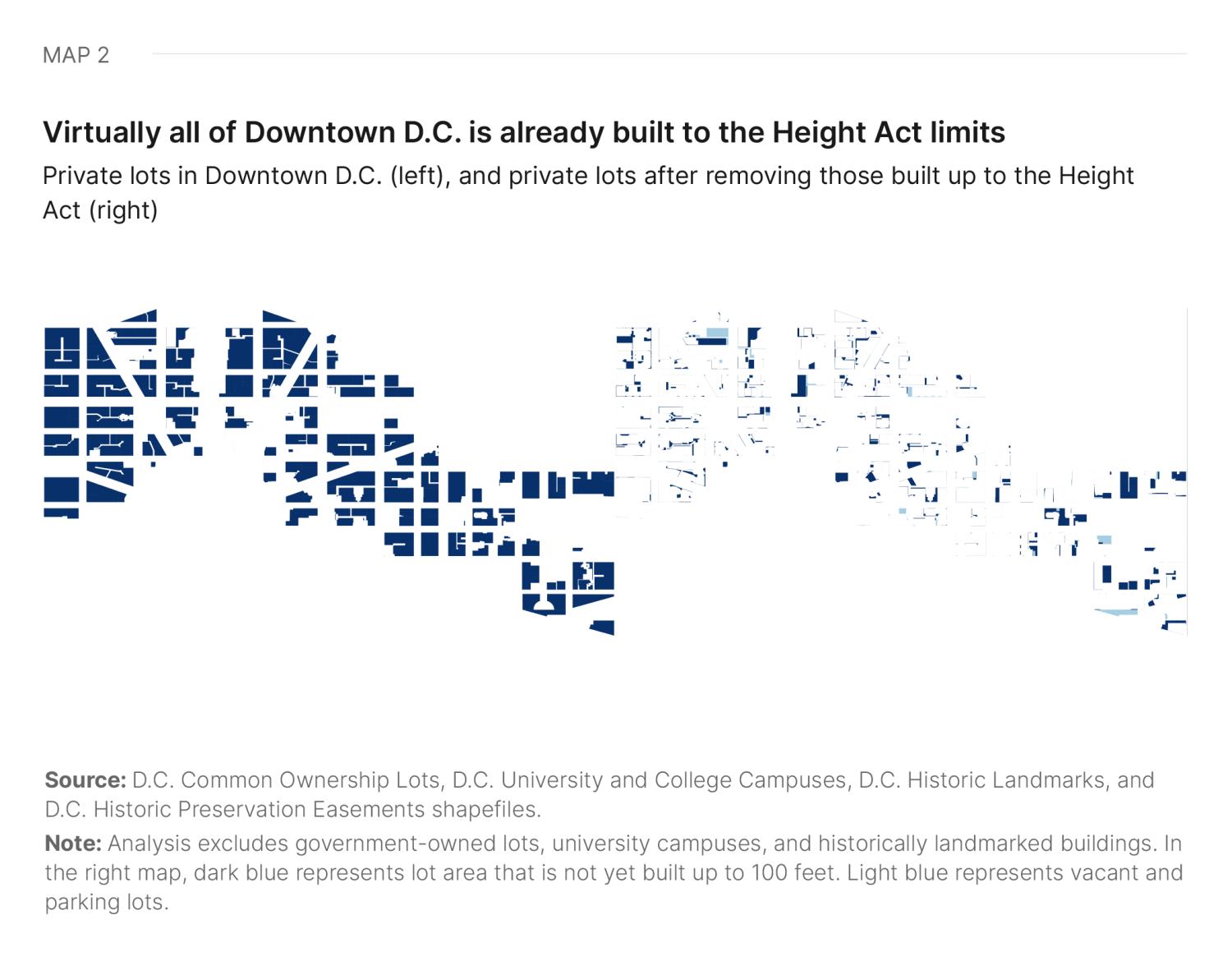

Map 2 shows that virtually all of downtown Washington, D.C. is already built to the Height Act’s limits. The map on the left plots private lots downtown, while the map on the right removes lot area that is already built up to 100 feet. The contrast reveals that there are scarce opportunities to replace shorter buildings with taller ones and even fewer vacant lots for infill development. Because of the Height Act, downtown Washington is effectively full, unable to expand its supply of building space.

The Height Act inflates downtown Washington real estate values and displaces development to nearby areas

Though the Height Act only restricts development in the District’s central areas, this is the natural location for tall buildings. Researchers have estimated that the value of land in central Washington, D.C. is more than 32 times higher than the value of land just 10 miles away.

When demand for downtown real estate exceeds the available supply, rent prices rise far above development costs. For 12-story buildings in the District, economists have calculated that rents are 63% higher than the minimum developable price. This markup is higher than all U.S. cities other than notoriously regulated San Francisco.

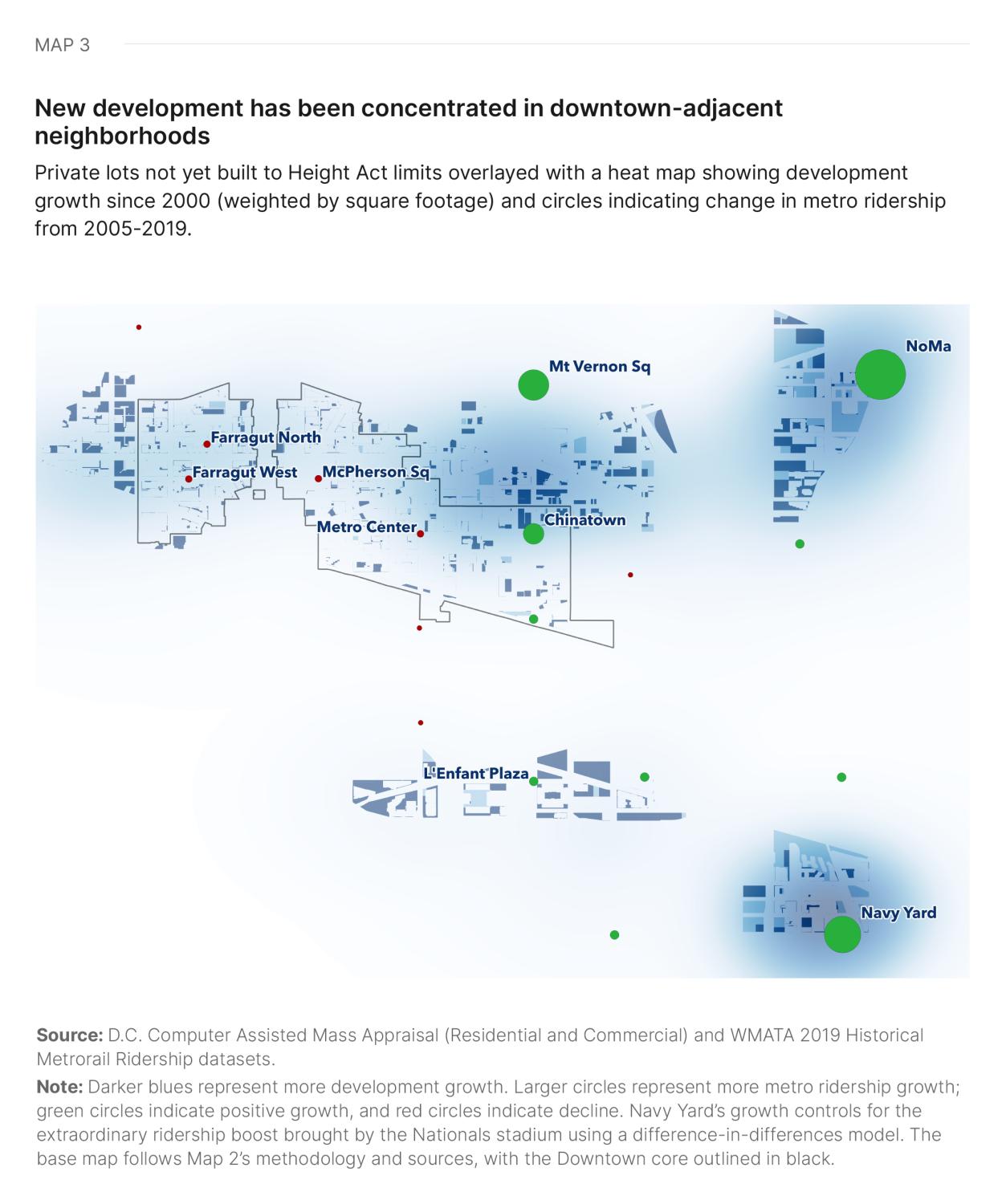

Artificially restricting supply in downtown Washington pushes prospective residents and businesses to outlying areas. In 2016, the District passed new zoning regulations that enabled the city’s downtown-adjacent neighborhoods like NoMa, Navy Yard, and Mount Vernon Triangle to build up to the Height Act’s limits. Unlike Downtown, these neighborhoods still contain significant space not yet built to the Height Act’s limits.

As a result, new development has been concentrated in NoMa, Navy Yard, and Mount Vernon Triangle, while downtown has hardly grown (see Figure 3). Likewise, ridership at the NoMa, Navy Yard, and Mount Vernon Square metro stations grew the fastest in the Washington, D.C. region from 2005 to 2019, while every central downtown station lost ridership (Map 3).

Distorting where development occurs harms existing and prospective residents

When residents and businesses who want to be downtown must instead find space in nearby neighborhoods, this shift in demand can raise real estate values in those areas, placing existing residents at risk of displacement. Neighborhoods can mitigate this risk by increasing their housing stock; expanding on a Montgomery County study, my report models that net displacement is unlikely when neighborhoods build at least three new housing units for every four new high-income residents. In fact, the low-income population has increased over the past two decades in neighborhoods that have abundantly developed to meet demand, including in NoMa and Mount Vernon Triangle.

But this strategy is ultimately unsustainable. Once downtown-adjacent areas reach the Height Act’s limits, they will no longer be able to accommodate the spillover demand from downtown. The cycle will then repeat. Real estate values will increase in downtown-adjacent neighborhoods as demand outstrips supply, and unmet demand will pressure further outlying communities to develop their way out of displacement.

Repealing the Height Act would create a more dynamic and inclusive downtown Washington, D.C.

While many appreciate the District’s unique skyline, most major U.S. cities—from Boston, to Chicago, to Los Angeles—had virtually identical height restrictions in the early 20th century. As these cities grew, however, they repealed these restrictions to accommodate new growth—except for the District.

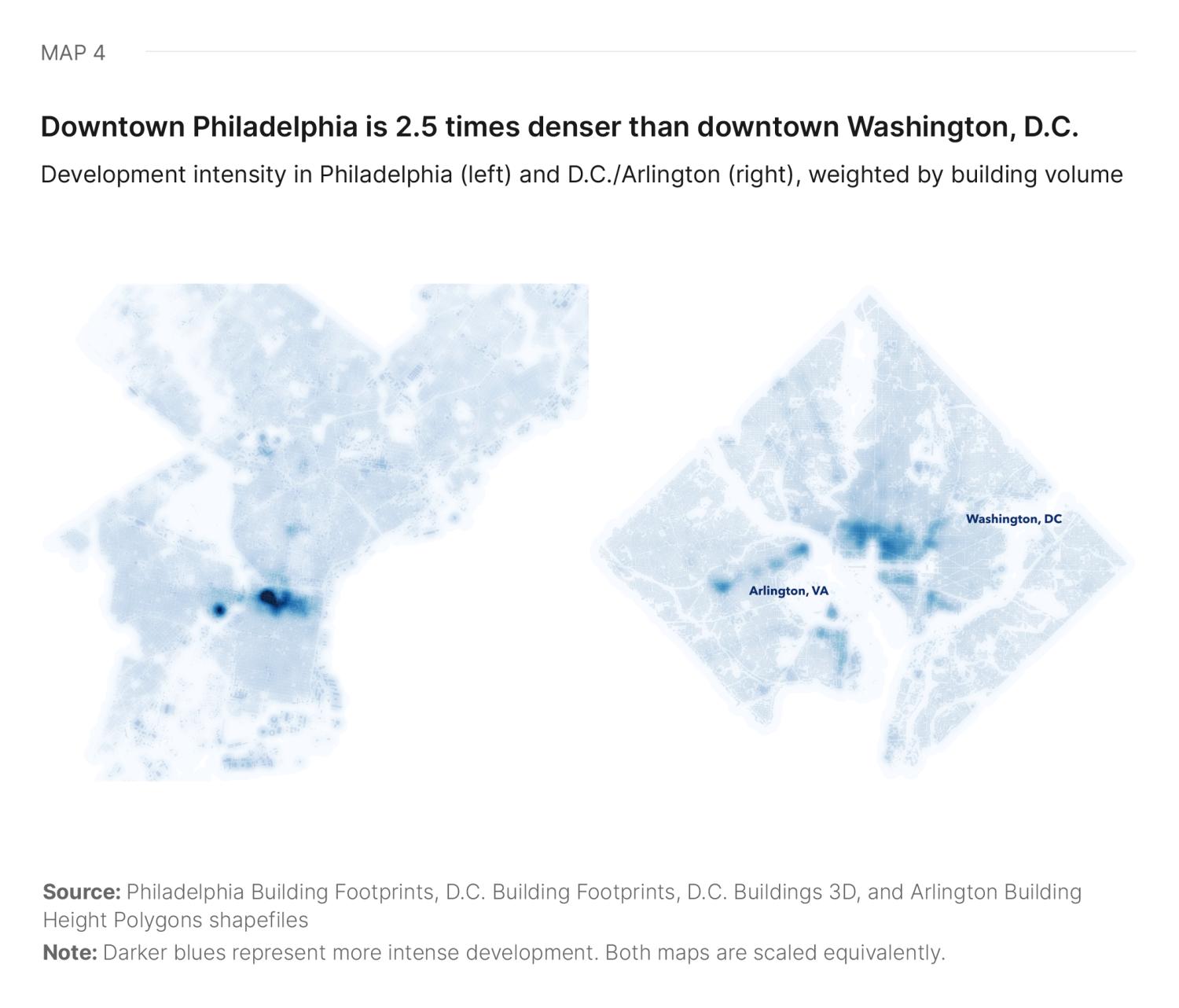

Without the Height Act, my report estimates that the District would have about as many skyscrapers as similarly-sized metros, such as Philadelphia and Boston. Map 4 compares development intensity between Philadelphia and the District to illustrate how much denser downtown Washington, D.C. could be.

Philadelphia’s downtown is more than 2.5 times denser than downtown Washington, D.C. While Philadelphia’s intense development is concentrated in Center City, the District’s midrise buildings sprawl miles from downtown. Washington’s pent-up demand for urban space even spills into Arlington, Virginia, where the burgeoning high-rise districts of Rosslyn and Ballston rival the density of downtown Washington itself. In fact, Ballston houses the densest residential census tract in the Washington, D.C. metro region.

When the Height Act pushes people and businesses outside of Washington, D.C. proper, the city cannot benefit from their contributions. Consequently, the District’s government estimates that the Height Act eliminates up to $115M in tax revenue each year—money that could be spent on public services.

While it would take an act of Congress, raising the height limit to the symbolic height of the 555-foot Washington Monument would preserve the District’s federal identity while offering the following significant benefits:

- Real estate values would fall closer to construction costs.

- More people could live and work where they most desire.

- The District could economically expand while minimizing displacement.

Amending the Height Act would enable downtown Washington, D.C. to grow into the dynamic and inclusive hub envisioned in Mayor Bowser’s $400M Downtown Action Plan, benefiting current and prospective residents alike.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Up or out: How the Height Act hinders development in Washington, DC

August 15, 2024