For Arab women, hard-won progress in education has not earned them the economic progress they deserve. Although young women seek and succeed in tertiary education at higher rates than young men, they are far less likely to enter and remain in the job market. Understanding and tackling the barriers that hinder women from working would unlock Arab women’s potential and yield significant social and economic benefits to every Arab State.

Echoing the trend observed globally, women in the Arab world outnumber men in pursuing university degrees. The ratio of female to male tertiary enrollment in the region is 108 percent. This ratio is even more favorable to women in Qatar (676 percent) and Tunisia (159 percent).

Yet, three out of four Arab women remain outside of the labor force.

Young women entering the labor market are disadvantaged in comparison to their male peers. Of female youth actively seeking work, 43.9 percent are unemployed in the Middle East, twice the male youth unemployment rate at 22.9 percent.

And, when an economic crisis occurs, women are the most vulnerable workers. For example, in North Africa, female youth unemployment increased by 9.1 percentage points after the most recent economic recession, as compared to 3.1 percentage points for males.

When taking into account both the low female labor force participation rate along with the high unemployment, only 18 percent of working-age Arab women have jobs. At this rate, it would take 150 years to reach today’s world female labor force participation average.

Success in education has not resulted in new and sustained jobs for women in Arab states. In a 2014 paper, I joined co-authors in describing this trend as a “boomerang effect,” wherein young girls are less likely to enter school but when they do, they outperform boys and are more likely to go on to university. However, once Arab women graduate from school, they are less likely to get a job. For example, in Jordan female college graduates are almost three times more likely to be unemployed than their male counterparts.

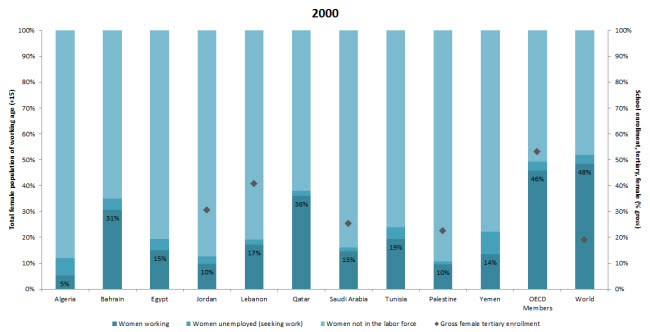

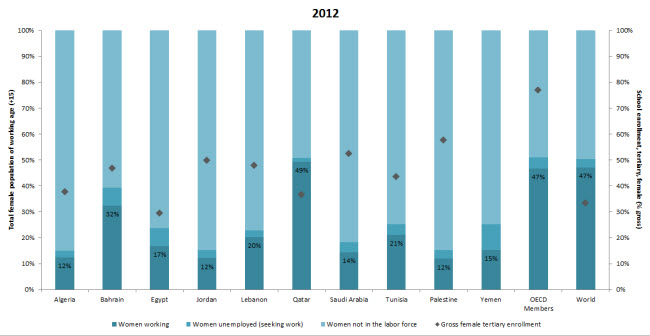

As the graphs below demonstrate, a comparison of the percentage of women employed regionally between 2000 and 2012 sees very little progress resulting from a higher educated female population. Despite progress in countries like Qatar and Bahrain, where women are increasingly part of the labor force, almost all MENA countries are well below the global average.

Figure 1. MENA women’s participation in the workforce and gross tertiary enrollment rates, 2000 & 2012

*Click on graph to enlarge

*Click on graph to enlarge

Source: Calculations by the author based on data from the ILO and the UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

The reasons behind why educated Arab women are not working are not yet fully understood and require more research. Recent studies (some of which are linked to below) point to a complex set of interrelated social, legal, and economic barriers holding Arab women back.

Understanding these barriers would have to consider the low level of jobs available in the Arab world, especially for young people. The Arab world is home to the largest number of unemployed youth in the world. Economic growth is simply not generating enough jobs for everyone.

Women, however, do not seem to have the support they need to compete for the few jobs that are available despite their high education levels and desire to work. In a 2010 World Bank survey of Jordanian female college graduates, 92 percent said they planned to work after graduation and 76 percent expected to do so full time.

A Brookings paper suggests traditional gender roles are reinforced early on in school curriculum and textbooks, influencing women’s decisions around work later in life.

Women are less likely to compete for the small number of new jobs generated by current economic growth as those jobs are most often in the private sector and in what is considered non-female friendly work. Instead, they overwhelmingly seek culturally accepted jobs such as teaching or other public sector work, with lower working hours and pay.

But when women reach the age of 25—around the age of marriage—they drop out of the workforce at high numbers.

For the few Arab women who choose the more challenging but potentially more rewarding path of entrepreneurship, in addition to the same challenges their male peers encounter, they struggle against family and personal laws that limit their ability to work independently or gain access to capital.

These barriers exist despite compelling evidence that moving women into the workforce is beneficial to themselves, their families, their countries, and beyond.

Women are more likely to spend a higher percentage of their earnings on their family and invest a larger part of their income on the education of their children, including girls.

In the Arab world, working women would raise their household income by up to 25 percent. If women worked in the same numbers as men, the GDP of every Arab state would rise significantly as a result. In the United Arab Emirates an equal number of women and men working would raise the country’s GDP by 12 percent; in Egypt, the same achievement would raise GDP by 34 percent.

Not all of the challenges women face in working are unique to the Arab world. Gender equality requires access to top jobs, equal pay, and flexible working hours that help women balance their roles as productive members of the labor force and as primary care-takers—issues that remain global challenges. The focus on women this month has brought many of those issues into sharp focus, with calls for addressing barriers to gender equality in work from every part of the globe. Particularly promising is the call by business leaders who are spearheading job creation and committing to offering more and equal opportunities for women.

In the Middle East and North Africa, businesses are beginning to recognize the significant opportunities of employing women, whether it is for their higher levels of education or for their insights into the growing purchasing power of women in some parts of the region. Experimental initiatives such as teleworking and flexible working hours have begun to emerge, especially in sectors driven by technology. These businesses understand that employing women does not only unlock their potential but also brings business value.

Much greater efforts and cooperation between the private sector and government are needed to replicate and scale up initiatives that tap the potential of working women.

Higher access to education without equal access to jobs is a lost opportunity for women, their families and their nations. Education alone does not fully protect or prepare women in the Arab world for gaining economic equality. Investment in education must be matched with national efforts to address all barriers to Arab women entering the job market and staying in it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Unlocking the potential of educated Arab women

March 12, 2015