Earlier this year, Brookings facilitated a daylong event focusing on outcomes-based financing in global health. Led by Brookings Senior Fellow Emily Gustafsson-Wright, this event brought together over 30 participants representing investors, funders, intermediaries, service providers, and researchers within the outcomes-based financing community from around the globe. This blog summarizes the discussion from the event.

While progress has been made toward achieving some of the subgoals of the third sustainable development goal, which calls for nations to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, we remain far off-track from meeting many of the targets. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated many of the ongoing health challenges and crises around the globe. For example, in 2023, there was a rise in cholera outbreaks, putting over 1 billion people around the world at risk. In more than 20 countries, mostly low- and middle-income, premature deaths caused by noncommunicable diseases have risen. The worsening climate crisis will only continue to deepen these challenges. The World Health Organization estimates that between 2030 and 2050, an additional 250,000 people will die from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress caused by climate change. The political instability occurring in many regions of the world also continues to deepen the health crisis as internal displacement limits access health and other public services such as clean drinking water and sanitation in addition to the effects of trauma and violence. To meet the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and save lives, there is an urgent need to do more.

Doing more, of course, requires funding. However, development assistance to health in the decade before COVID-19 was largely stagnant at approximately $40 billion to $45 billion per year. While this amount significantly increased in the first year of the pandemic, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates that it has dropped steadily since 2021. The continent of Africa alone is short $66 billion annually to finance its health needs. The World Bank estimates that by the next decade, the annual financing gap for the 54 poorest countries in the world will be over $175 billion dollars. Compounding these issues is the growing debt distress crisis in low-income countries. Taking this into account, the World Bank estimates that 41 countries will have a reduced spending capacity—real per capita government spending below the 2019 rate—through 2027. The same report estimates that a further 69 will see their spending capacity rise only slightly above pre-pandemic levels in the same period, affecting health care spending capabilities. These pressures highlight the need to use capital effectively, especially given the expected increasing impact of climate change.

Innovative financing may provide an opportunity to meet the pressing needs in the global health space. Innovative financing can serve to increase (i) the amount of funds through the mobilization of new sources, (ii) efficiency of funding by a reduction in service provision time and costs, and/or (iii) effectiveness by being impact-led with a heavy focus on results.

Global market for outcomes-based financing

Outcomes-based financing (OBF) is an innovative financing mechanism in which investors provide risk capital needed for an intervention or program, and then are conditionally repaid on the basis of independently verified outcomes. Through the use of social impact bonds (SIBs) and development impact bonds (DIBs), outcomes-based financing has been applied, in limited cases, to health challenges.

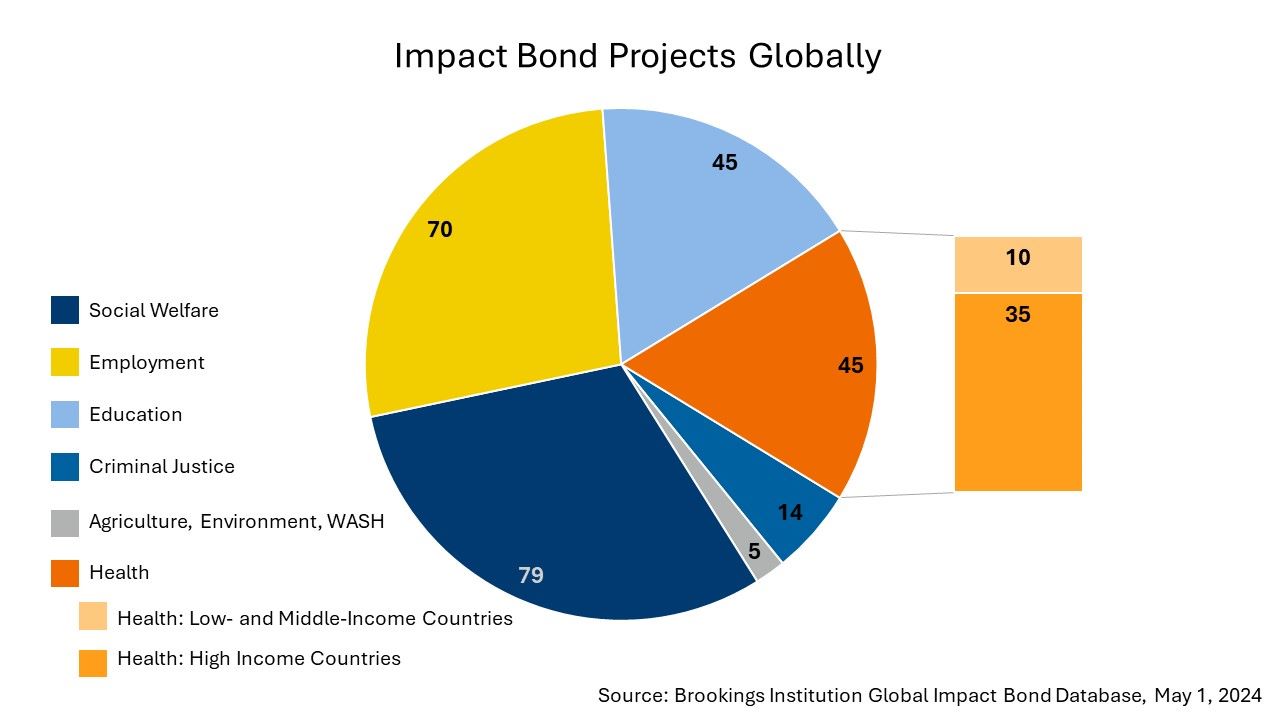

Since 2010, when the first SIB was launched in the United Kingdom, nearly 260 impact bonds have been implemented in 40 countries worldwide. As seen in the graphic below, of 258 impact bonds in the Brookings Global Impact Bond Database, only 10 impact bonds have been implemented in the health sector in low- and middle-income countries.

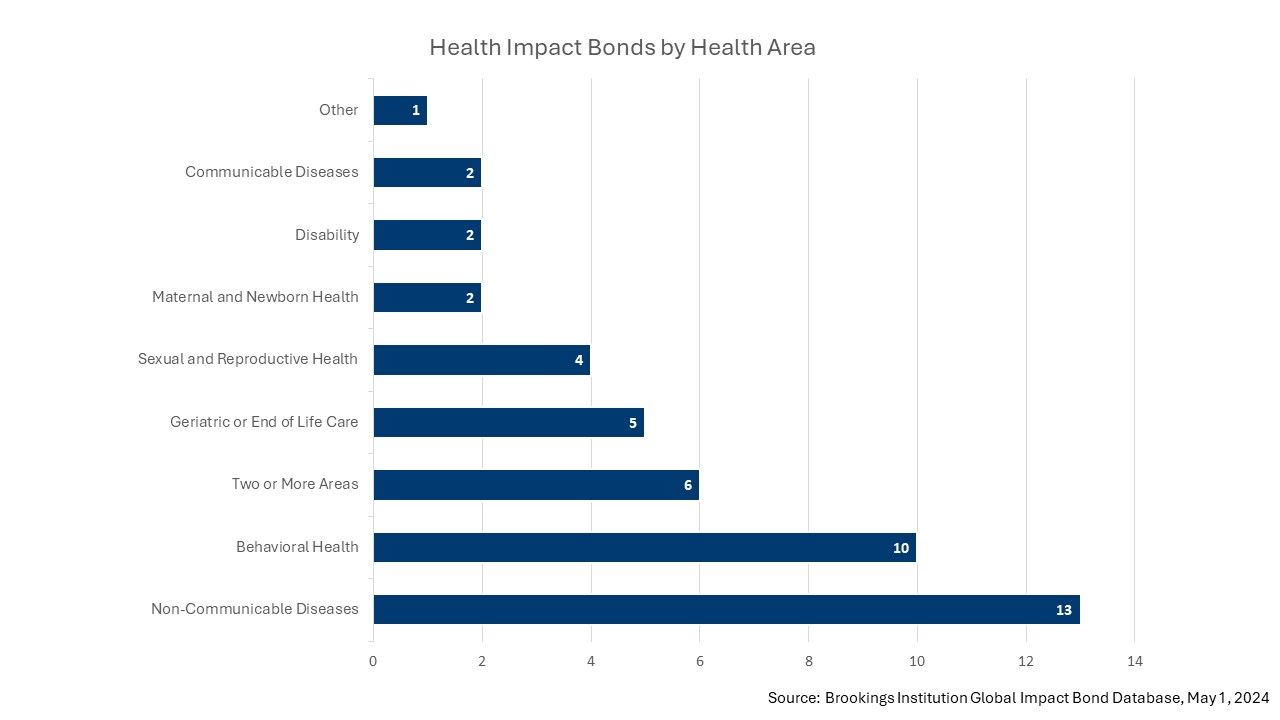

Of the 45 health impact bonds implemented globally, the majority focus on non-communicable diseases and behavioral health, with just 2 focusing specifically on communicable diseases, as seen below.

While each outcome obtained is a step in the right direction, 45 projects worldwide is not nearly enough to make a breakthrough.

Identifying opportunities for outcomes-based financing in health

Considering the possibility of much-needed benefits like increased quantity, efficiency, and effectiveness of funding, what opportunities exist to expand the use of OBF in the health space? First, using outcomes-based financing, versus more traditional mechanisms, only makes sense when certain considerations are met. If the legal and regulatory frameworks for paying for outcomes do not exist within the country or funding organization, for instance, OBF would not be a good option. Similarly, OBF requires the presence of outcomes funders who are committed to the achievement of outcomes and service providers that can actually deliver them. In addition, the choice to use OBF versus traditional methods should be made when there is both a belief that paying specifically based on verified outcomes is more likely to get those outcomes and a risk that can be shifted from the outcome funder and/or service provider to the investor. At bare minimum, there must be a clear and explicit treatment, with evidence that it is effective, an equally clear and explicit outcome, and an incentive structure matching the outcome.

Determining an outcome that is worthy of an OBF project is critical. Over the last decade of research in this space, Brookings has identified several characteristics that should guide the selection of outcomes. Outcomes should be:

- Meaningful – worthy of the cost of an OBF project

- Measurable – able to be measured within the actual context and timeline

- Malleable – obtained through an intervention with flexibility to respond to real-time monitoring and during the proposed time period and context of the project

- Monetizable – represent cost savings or avoidance. In low-income contexts, identifying direct monetizable savings can present a challenge.

Within the health sphere, there are several areas where OBF could potentially be applied. This includes fields such as both communicable and noncommunicable diseases, mental health, maternal and child health, neglected tropical diseases, and antimicrobial resistance. OBF could also play a role the development and deployment of health products and technologies like drugs, vaccines, devices, software, diagnostics, and personal protective equipment. Finally, services such as pandemic preparedness, local manufacturing, delivery chains, financial protection, and disease surveillance provide further potential opportunities. OBF may be a better fit for some of these areas than others, with the characteristics laid out above providing some guidance as to which outcomes would be best suited for such a financing mechanism.

Challenges to implementation of outcomes-based financing

Although there are many opportunities to employ outcomes-based financing in the health sector, there are several challenges that must be overcome for OBF to be applied at scale. These challenges exist at all stages of a project. To get a project off the ground, all stakeholders must be able and willing to commit themselves to using a new approach that does not fit neatly within familiar structures. Similarly, long timelines for approval of OBF projects that do not match traditional frameworks can make conventional grant-based programs more attractive in the short term. These issues must be addressed to move from the design phase into implementation.

If these hurdles are overcome, more challenges remain throughout the life of the project. OBF projects involve multiple players, including investors, implementors, funders, and third-party evaluators, and sometimes also performance managers, legal counsel, and various other intermediaries. Keeping all of the stakeholders coordinated throughout implementation can be burdensome. The monitoring and measurements associated with an OBF project are critical to determining if the project is a success and what repayment, if any, will occur, but add an additional cost and potential challenges. Social outcomes can be difficult to measure precisely and may have margins of error so large that it is statistically impossible to determine if a project has truly been successful. Similarly, it can be difficult to ascertain whether the results achieved are fully attributable to just the intervention or if an extraneous factor fed into the findings. Also, some social outcomes exist on a time continuum far greater than a project’s life which may be longer than investors are willing to wait for repayment.

Outcomes-based financing in action in global health

While these challenges are considerable, they are not insurmountable. Engagement with government may be one way forward in making progress overcoming these challenges. Some examples of outcomes-based finance for health across the globe include the Utkrisht DIB in India, which focused on improving maternal and newborn health and completed in 2021; the Hepatitis C DIB in Cameroon, which focused on curing individuals with Hepatitis C and completed in 2022; the Stevig Staan (Standing Strong) impact bond in the Netherlands, which is currently in implementation and focuses on elderly fall prevention; and the Monami project in Angola, which is currently in development to improve maternal and newborn health.

These projects highlight the positive outcomes that can be achieved with OBF. This includes 13,000 estimated lives saved in India through the Utkrisht DIB, a 96% cure rate of participants in the Hepatitis C DIB in Cameroon, prevention of 45 falls in the first year of Stevig Staan, and the design of a localized project using an Angolan service provider. These outcomes represent the promise of OBF to improve the lives and livelihoods of individuals around the world through improved health.

Nevertheless, and although they are based in different contexts and are at different stages of development, stakeholders from these projects shared some common challenges that will need to be addressed to support the future development of additional projects in health, including, for example:

- Obtaining strong and sustained government involvement.

- Attracting outcome payers.

- Determining higher-level health impacts that are complex, long-term, and influenced by many factors.

- Finding cost-effective ways to monitor and measure outcomes.

- Setting up the OBF mechanism in a reasonable timeframe.

The future of OBF in health

Determining where OBF could fit in most naturally and effectively, as well as when and how to engage government, could help make that promise a greater reality. Finding areas where public spending has not moved the needle much may represent a natural opening. At the same time, it is critical to understand a country’s priorities in their health care system, and work within those priorities for the most traction. One example from the workshop demonstrated that there is a high chance that non-priority issue areas will not be taken up by the government at the conclusion of the OBF project and therefore may not be a sustainable choice.

This highlights the critical need to engage government from the start. Working with government and existing institutions and structures within the country is likely to be much more effective (and sustainable) than forcing external priorities with complicated financing structures. Making OBF part of the solution for government, and not an additional problem to deal with, is also crucial. This means reducing complexity and finding evidence beyond “health savings,” which are not cashable, that persuade treasuries and finance ministries to get on board. Considering that many OBF projects have been smaller, with an average of less than 44,000 beneficiaries reached with an average upfront budget of $2.3 million, it is currently difficult to make the cost savings argument compared to billion-dollar grant programs that benefit from their sheer scale. One possibility is linking OBF with debt swaps, which could speak to the financial considerations treasuries and finance ministries would respond to. Building strong ties with government early on can increase their capacity to use innovative methods like OBF to solve their own health priorities and obtain better outcomes for their citizens.

In conclusion, we already have evidence that unlocking the promise of outcomes-based financing in the health sector is possible. With the world at a critical junction, with an urgent need to ameliorate the most pressing health issues amid the ever-intensifying climate crisis the question is will outcomes-based financing rise to meet the challenge and who will be the brave big movers in this space?

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or the funders acknowledged below.

Brookings gratefully acknowledges the support of PharmAccess and the LEGO Foundation.

Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment. A full list of contributors to the Brookings Institution can be found in the Brookings Institution Annual Report.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Transforming the future of global health

The potential of outcomes-based financing

June 14, 2024