Black Americans comprise about 14.2% of the U.S. population, yet Black-owned businesses represent 12.7% of all sole proprietorships and only 2.4% of employer businesses. These disparities don’t only hold back Black entrepreneurs—they also restrict economic opportunities for entire communities, which in turn impacts local prosperity. Data shows a correlation between metro areas with more equitable representation of Black-owned employer businesses and higher well-being scores for Black residents. If the share of Black employer firms matched the Black population share (like their Asian American and white counterparts), it would benefit the entire economy and overall well-being for Black people.

Employer businesses are part of the built environment, shaping local economic conditions and thus contributing to the opportunities, vibrancy, and infrastructure of a place. The share of Black-owned employer businesses, among other factors, is a gauge that indicates the extent to which Black business development is suppressed and, by extension, how structural racism is likely to impact other facets of everyday life. Thus, comparing metro areas’ progress toward more equitable rates of Black-owned employer businesses could provide insights into where and why Black communities are thriving.

To understand the place-based relationship between Black-owned businesses and Black well-being, this report combines recent insights from our research on the state of Black-owned employer businesses and our Black Progress Index. We use the Index, which estimates Black life expectancy, as a measures of overall Black well-being, and rates of Black-owned employer businesses as an indicator of each metro area’s relative progress toward a more equitable regional economy. Because both factors vary by place and are influenced by other environmental and social factors that predict structural racism, they can provide insights into how Black-owned businesses may improve, or at least help us to understand the determinants of Black well-being.

Overall, this data illustrates that equity pays—not only in terms of wealth generation, but also overall Black well-being and prosperity.

The percentage of Black-owned employer businesses is a poor predictor of Black well-being

Well-being is a crucial aspect of advancing shared prosperity. While well-being can be measured in a variety of ways, it typically captures individuals’ subjective mental state and attitude toward their circumstances and environment. Unlike other indicators of prosperity such as GDP, income, or unemployment, well-being is more holistic, emphasizing our relationships with the people and places we interact with. For this reason, well-being more accurately captures the complex ways that a history of racist policies can compound into the present and expose Black communities to overlapping barriers to health, wealth, amenities, and crucial services. Conversely, it can also provide insights into the place-based factors that explain where and why people are thriving.

Recently, we explored Black well-being at the metro area level using Gallup survey data on the percentage of individuals who reported they were thriving. This is a measure of subjective well-being, with those considered “thriving” having high well-being now and an optimistic outlook of their future.The areas where Black people were thriving most—such as Huntsville, Ala.; Augusta-Richmond, Ga.-S.C.; Killeen-Temple, Texas; Washington, D.C.; and Atlanta—are all correlated with greater individual and community stability, high racial and ethnic diversity, and lower rates of “deaths of despair” caused by suicide, alcohol, or drug abuse.

These places are also booming for Black-owned employer businesses. In Huntsville, Black-owned employer businesses have grown by 25% since 2017. In Augusta-Richmond and Killeen, they grew by 38.3% and 41%, respectively. In nine of the top 10 ten areas for Black thriving scores, Black businesses are growing faster than the national average.

Nationally since at least 2008, average Black well-being has deceased quicker than other racial and ethnic groups. But when we look at metro-level changes, this is not always the case. The above cities buck the national trend, indicating that something unique about these places could be bolstering Black well-being.

Another place-based and relational indicator of overall Black well-being is life expectancy. Our Black Progress Index, which estimates Black life expectancy across U.S. metro areas, shows that the percentage of Black adults who own a business is one of the most important environmental factors that positively predict local life expectancy. Alongside other factors such as Black homeownership rates, median income, and educational attainment, a higher density of locally owned Black businesses is an indicator of higher Black prosperity.

However, when focusing only on employer businesses rather than all businesses, there is a negative relationship with Black well-being. Metro areas with a higher percentage of Black-owned employer businesses tend to have lower Black Progress Index scores. Figure 1 shows that as the percentage of Black-owned employer businesses among all businesses decreases, scores in the Black Progress Index increase. Compared to sole proprietorships, employer businesses can generate local employment opportunities, influence the value of property in the region, and even contribute to livability. But this negative correlation would appear to indicate that diversity in employer business ownership is not important for improving local well-being.

This counterintuitive result likely reflects that Black life expectancy tends to be higher in metro areas with proportionally fewer Black residents and lower rates of Black-owned employer businesses. In Figure 1, metro areas with larger Black populations are clustered in the top left, showing that a higher percentage of Black-owned employer businesses is correlated with a lower life expectancy. But why is that?

One explanation may be related to increased access to positive predictors of health in metro areas with smaller Black populations. White privilege can be understood as a spatial phenomenon that has concentrated greater access to wealth-building opportunities—such as higher housing values, neighborhood assets, and healthier and safer environments—in white-majority spaces. Of course, this is ignoring the costs that can accompany accessing white spaces: exposure to racism and its impacts on health and well-being, as well as barriers to entry such as higher property values and costs of living. Conversely, living in Black-majority spaces can entail its own costs, such as devalued housing prices and commercial properties, less corporate investment, higher property taxes, and exposure to dangerous pollutants. Ultimately, Black residents living in metro areas with higher Black populations shouldn’t be penalized. These metro areas, many of which have a history of racialized devaluation and disinvestment, should have the same opportunities for wealth-building as non-Black communities.

Metro areas with more equitable representation of Black-owned employer businesses have higher Black well-being

A stronger predictor of overall Black well-being is how equitable the local business environment is, measured by the ratio of the Black population share to the share of Black-owned employer businesses. In an equitable economy with no structural barriers for would-be entrepreneurs, we would expect to see the percentage of Black-owned employer businesses equal to the percentage of Black residents. However, no metro area has a percentage of Black-owned employer businesses that equals or exceeds the percentage of Black residents. Moreover, as the share of Black residents increases, the demographic distribution of businesses tends to become more inequitable.

Figure 2 shows the correlation between this equity ratio and overall Black well-being, again measured by the Black Progress Index, with dots scaled to the metro area share of the Black population. Unlike measuring only the percentage of Black-owned employer businesses, this metric shows a positive relationship: A more equitable environment for Black-owned employer businesses is correlated with higher overall Black well-being. Indeed, of the 10 metro areas closest to reaching equitable rates of business ownership, only one (St. Louis) has a Black Progress Index score below the 50th percentile. Four of those 10 cities (Oxnard, Calif.; Portland, Maine; Reading, Penn.; and Washington, D.C.) have Black Progress Index scores above the 80th percentile.

Of course, this is correlation and not causality; creating a more equitable distribution of business owners will not necessarily increase Black well-being. However, it’s likely that some of the harder-to-measure impacts of structural racism on Black well-being—such as the ways that it may have shaped local housing and zoning policy to act as de facto segregation, or perpetuated racial bias among local lenders—are being captured in this relationship. By controlling for the share of Black residents (and thus to some extent the historic penalty of residing in a Black-majority neighborhood), this metric shows how equity in business ownership may provide an indication of how much structural racism is still holding back gains in Black well-being.

As part of the built environment, employer firms shape the contours of daily life across communities, neighborhoods, and entire metro areas. They provide opportunities for employment and local wealth creation by drawing external investment; they contribute to the character and vibrancy of neighborhoods; and they influence the wealth and prosperity of a place’s residents. A more racially representative set of business owners could indicate that structural racism is less of a factor in determining the make-up of the local environment, and thus less influential on the overall well-being of nonwhite residents.

At the individual level, the extent to which Black-owned business growth directly benefits Black households, especially low-income households, is questionable. Business growth is not necessarily inclusive, and can also inadvertently worsen wealth divides even when helping to ameliorate racial divides in ownership. However, at least at the metro area level, reaching toward equity in employer business ownership could be a crucial factor in advancing shared prosperity.

A typology to understand metro-area-level progress toward equity

If equity in employer business ownership is an important indicator of creating more livable and prosperous regions for Black Americans, it follows that we need a better understanding of where and why some metro areas are more inequitable than others.

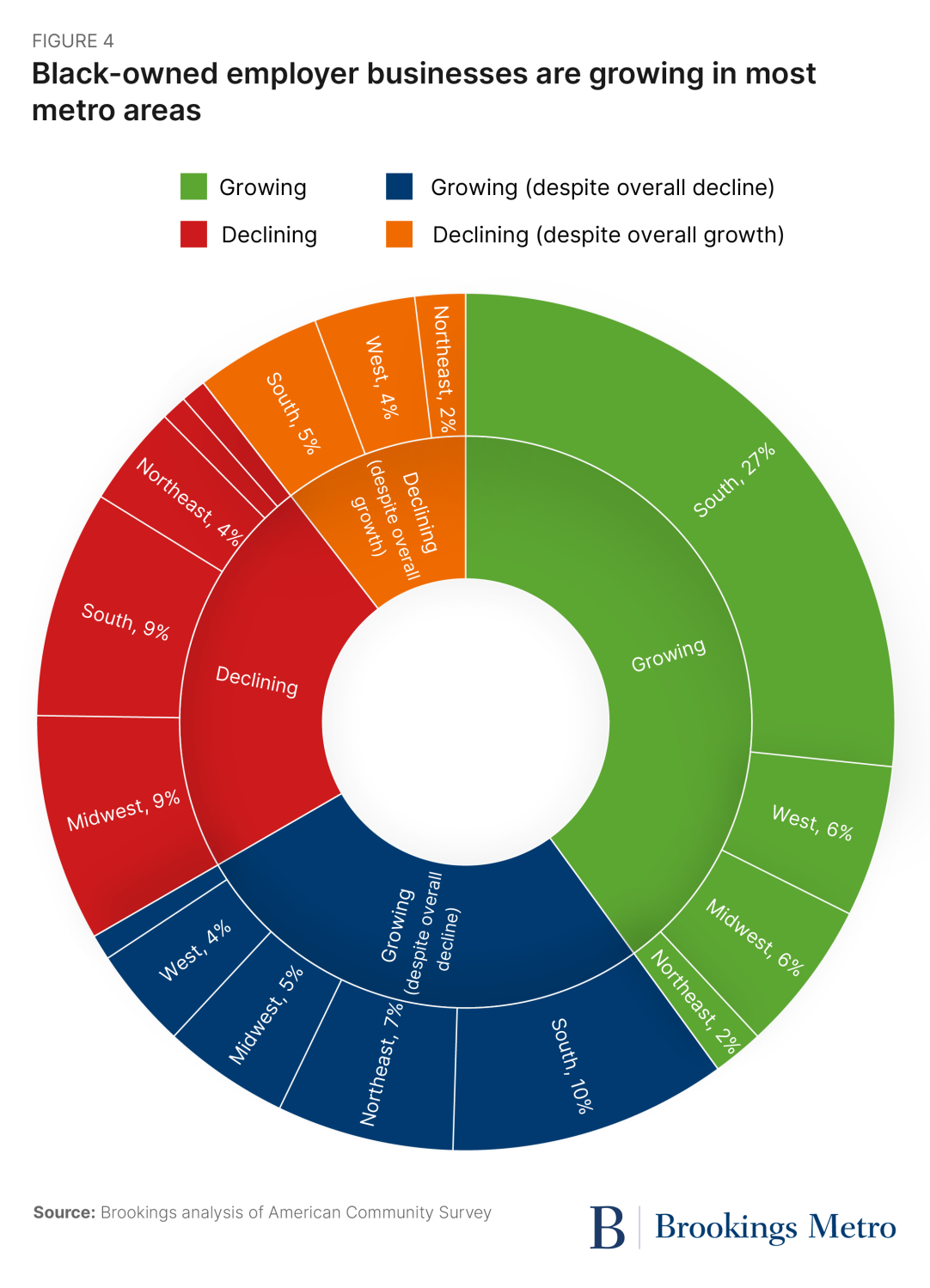

To gain this deeper understanding, we adopt a typology of Black business growth, breaking each metro area into one of four categories:

- Metro areas where Black-owned employer businesses and all other businesses are growing

- Metro areas where Black-owned employer businesses are growing despite declines in overall businesses

- Metro areas where Black-owned employer businesses and all other businesses are declining

- Metro areas where Black-owned employer businesses are declining despite growth in overall businesses

Figure 3 shows where each metro area falls along this typology. The growth in total employer businesses is on the x-axis and growth in the number of Black-owned employer businesses on the y-axis.

There are no strongly shared geographic factors among the metro areas in each quadrant, as growth and declines are spread across city size and geographic region. However, the variable ways that metro areas are becoming more or less equitable for Black-owned employer businesses highlight the need for a more structured pursuit of equitable growth. The inconsistency between Black business growth and overall business growth is also a warning that economic growth is not always racially inclusive, and a reminder that progress toward a more equitable environment can and should occur even in periods of economic decline.

Promisingly for Black well-being, Figure 4 shows that 67% of all metro areas have seen growth in Black-owned employer businesses since 2017, including 27% of metro areas that saw growth despite declines in firms overall. In 40% of all metro areas (primarily in the Southeast) Black-owned employer businesses have either benefited from or been a driver of overall growth. This includes Black boom towns such as Atlanta and Greenville, S.C., where Black-owned employer business growth has substantially outpaced overall business growth: 27.5% and 88.9%, respectively, compared to 6.1% and 9.4% for all businesses.

However, 23% of cities have seen declines in the overall number of employer businesses since 2017, and Black businesses have borne the worst of the impacts. In Baltimore, for example, Black-owned employer businesses have declined by 15.8%, compared to 2.2% for all businesses. Atlantic City, N.J. is even starker, with declines of 66.9% for Black-owned employer businesses and 9.2% overall.

Meanwhile, 10% of cities have become more inequitable. In Pittsburgh, Houston, and Lexington, Ky., for example, the number of Black-owned employer businesses has declined despite growth in the total number of businesses. The top regions for such declines were the Midwest (where 45% of metro areas had a declining number of Black-owned employer businesses) and the West (where 27% of metro areas had a declining number of Black-owned employer businesses).

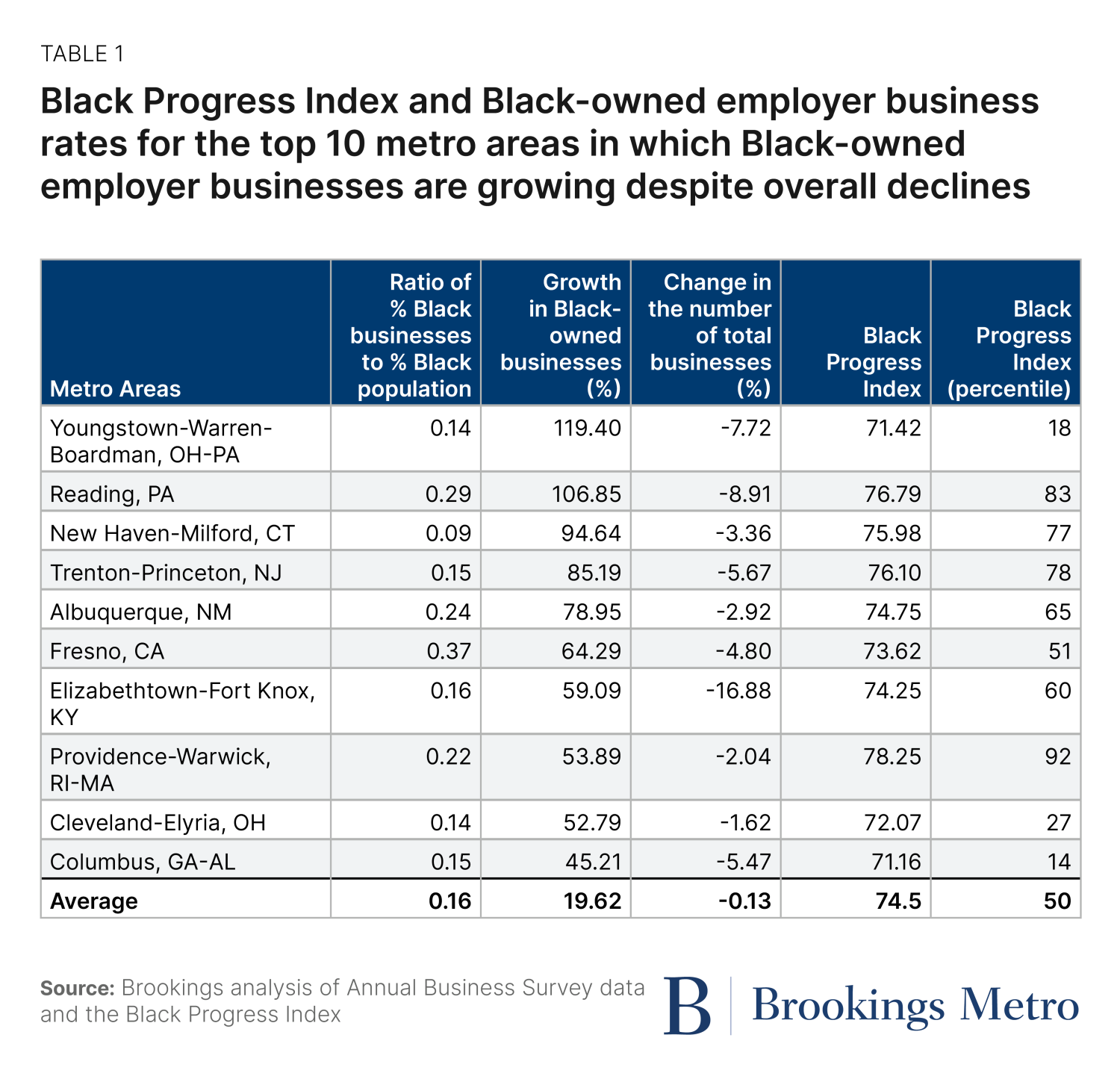

While overall economic prosperity plays a clear role in shaping the conditions for more equitable rates of employer firm ownership, metro areas in the top left quadrant of Figure 3 (such as Flint, Mich.; Reading, Penn.; Durham-Chapel Hill, N.C.; and Oklahoma City) have flourished for Black-owned employer businesses even while the overall number of businesses has declined. Table 1 shows that only 45% of these cities have above-average Black Progress Index scores; however, a continuation of these trends may see an improvement in Black well-being over the long term.

Tracking rates of equitable employer business ownership to understand place-based well-being

Equity is a stimulus, and at least to some extent, pays dividends in well-being. The extent to which employer business owners reflect the racial and ethnic composition of the local population positively predicts high overall well-being. In fact, it’s a stronger predictor than the percentage of Black-owned businesses and the number of sole propietorships. Yet no metro area across the U.S. has a share of Black-owned employer businesses equal to or greater than its share of Black residents. Local governments and corporate America are missing an opportunity to enhance well-being by investing in racial equity.

The variable ways that Black-owned employer businesses experience growth and declines indicate that we need a more structured approach to equitable growth. It’s clear that improving local economic conditions can uplift Black-owned businesses and is part of creating the conditions that help Black residents thrive. But alone, this is not a silver bullet. Structural barriers that have created and continue to perpetuate an unequal system can lead to uneven growth, hobbling Black entrepreneurs and trapping Black businesses in declines during downturns. Removing structural barriers to a more equitable business environment—one that creates opportunities for a diversity of business owners—could be a core part of building local economies that work better for diverse residents.

While at the individual level, the extent to which equity in business ownership is a pathway to well-being is debatable, progress toward equity could be another useful indicator for tracking shared prosperity. As a correlate for other place-based indicators of racial progress, tracking inequitable rates of employer business ownership could help metro areas better understand the role that structural racism is playing in restricting or advancing the conditions for Black well-being—especially when the impacts of racism are less apparent.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).