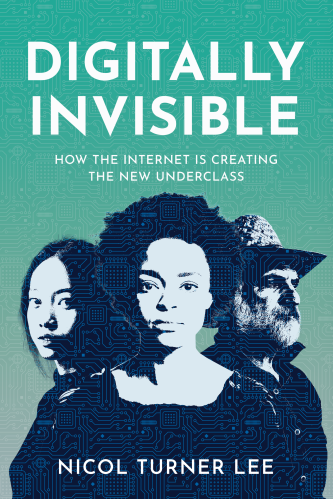

Around the end of 2017, I started writing my new book, “Digitally Invisible: How the Internet is Creating the New Underclass,” after bringing the idea to Brookings Press and close colleagues who knew about my decades-long career in the community technology movement. Over three years, I embarked on field research across the United States, which I soon referenced as a “digital divide tour.” The tour included seven cities and small towns to understand how people experienced the internet and the extent to which their access benefited them. Between 2018 and 2020, and right before the global health crisis would upend life as we knew it, I visited Cleveland, Ohio; Garrett County, Maryland; Hartford, Connecticut; Marion, Alabama; Phoenix, Arizona; Staunton, Virginia; and Syracuse, New York.

Each location brought me to people in their own spaces and places, including small business owners on the main streets of rural towns, farmers in very remote areas, and community activists whose daily lives revolved around the front porch of their homes. On each visit, I discovered how everyday people were navigating their online lives, and I quickly learned about their future aspirations, which were largely being dictated by technological advancements. I also quickly gleaned from my travels that D.C. policymakers from both sides of the aisle were stuck in one-size-fits-all public policies for universal connectivity that often were doing more harm than good to the people in these communities.

Even though the lives of the people that I visited were different from those of us who are seamlessly connected to the internet, their experiences became more normalized when millions of people discovered the importance of an internet connection amid the global pandemic that upended everyone’s lives. What began as weeks, then months and years, of physical and social isolation in March 2020 meant that more people had to rely upon an internet connection to work, access health care, do homework, and communicate with loved ones. That was especially true in the underserved parts of rural and urban America that not only lacked high-speed broadband access but were also struck by the consequences of historic structural and economic constraints, which hindered their full participation in society.

Unlike more privileged individuals and communities, millions of people in these areas struggle to find work, access quality health care, and even learn as society moved from offline to online activities. In the book, I refer to the latter as “digitally invisible” populations because they live in parts of rural America where there are more cows than people. They remain trapped in geographically redlined urban and suburban areas where structural racism has resulted in rapid disinvestments and slow digital access. They struggle to maintain conspicuous identities amid substantial systemic barriers, which have become more economically harmful and medically dangerous to those who remain in an analog, in-person world.

In other words, the digitally invisible are trapped by their own demography, geography, and circumstances. As a result, they are limited in a world no longer bound by the physical bearings of classrooms, apartment complexes, farms, or other business establishments.

Throughout the book, I bring visibility to these individuals and their communities to draw attention to how disparate connectivity has become a social and economic determinant of one’s quality of life and well-being. For example, you will meet Joseph from Staunton, Virginia, who is unable to work because the artificial data caps of his mobile phone make it hard for employers to place him in temporary daily opportunities. You will meet Principal Cathy from Marion, Alabama who, having previously benefited from a now-defunct Obama administration effort to connect schools and libraries, provided more than 700 tablets to her students in a K-12 Black rural school. However, these tablets became more like “books without paper” when the pandemic hit because students didn’t have a home or community broadband connection. You will meet Jon, who, as part of a legacy of four generations of farmers, has been unable to compete with more advanced, highly technical farming companies because his access to robust connectivity stopped at the edge of his property, making it more difficult for him to thrive. These and other stories throughout the book reveal what life is really like for the millions that are not connected.

These personal stories should encourage more pragmatism among policymakers, industry experts, and other stakeholders who are making major decisions and investments targeted to efforts that will ultimately close the digital divide. For more than three decades and six presidential administrations, we have dealt the same cards on this significant policy issue. To get to a more digitally just, productive, and smart economy, how we handle the concerns of people and their communities on matters of connectivity must be central to future interventions.

If we are to be honest as a nation, these last three decades of technological acceleration have left people more as passive consumers than active producers, innovators, and skillful workers in a 21st century economy. And our national policies continue to conform to this model. For example, the partisanship-fueled elimination of the Biden administration’s Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), which provided more than 20 million eligible participants with discounted monthly internet service, undermined the program’s goal of ensuring that people could live, learn, earn, and ultimately thrive in a society where being connected translates into greater economic competitiveness. In the book, I provide a detailed plan for how we can build a thriving digital economy—one that sees universal access as central to the U.S.’s global competitiveness.

Moving toward digital visibility

Most people believe that the digital divide began at the start of the pandemic when school-age children from across the world had to transition online for learning, or as remote health and scheduling of medical appointments became the norm rather than the exception. Instead, readers will come to know the fuller history in my new book, including how I also first encountered the transformative power of technology back in the late 1990s as I built and shepherded computer labs in the city of Chicago.

But whenever and however you learned of this very important issue is not that important. It is time to enact more appropriate policy and programmatic interventions that aggressively challenge and embrace the importance of universal access to the nation’s existing and emerging communications infrastructure. Equally important is to meet people where they are and acknowledge their individual and community aspirations for being connected into the future; their lives depend on it.

Nicol Turner Lee is a first-time author of the book, “Digitally Invisible: How the Internet is Creating the New Underclass” (Brookings Press, 2024), which is now available wherever books are sold. For more information about Dr. Turner Lee, and the book, you can also visit www.nicolturnerlee.com.

Commentary

The realities of being digitally invisible in the 21st century

August 8, 2024