Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of The Primaries Project series, where veteran political journalists Jill Lawrence and Walter Shapiro, along with scholars in Governance Studies, examine the congressional primaries and ask what they reveal about the future of each political party and the future of American politics.

The June 10 primaries will be held in five states including South Carolina, Virginia, and Nevada and will probably not make much news. Of course there could be some headlines. In South Carolina, Senator Lindsay Graham is being challenged by several candidates including a Tea Party candidate and could come in short of the 50% he needs to avoid a runoff. And in Virginia’s 7th congressional district, some polls show House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s lead over Tea Party challenger Dave Brat closing. Assuming Cantor wins, a small margin of victory will provide fodder for speculation that he may be vulnerable in the future.

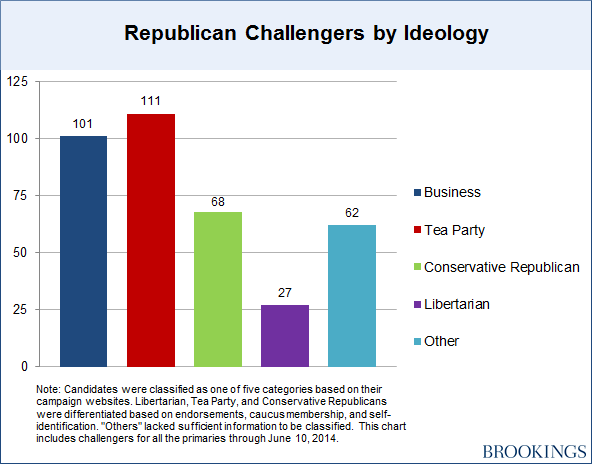

But apart from the headlines, here at Brookings we’re looking at the underlying trends. And a few insights emerge from what we’ve found so far. As the first graph illustrates, the Republican Party continues its civil war between more mainstream business-oriented challengers and Tea Party or conservative challengers on the right. There are also a fairly large number of “other” candidates, the majority of whom are classified as such because they don’t have a website or any other public information available.

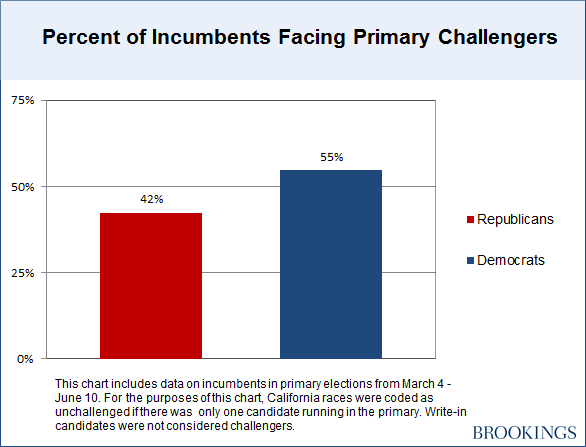

The next chart, however, yields a bit of a surprise. Until now both conventional wisdom (and our own data) have shown much more conflict on the Republican side of the aisle. Democrats don’t seem to be as internally conflicted this year as Republicans. And yet, as we see, Chart #2 shows more Democratic than Republican contests. What’s going on?

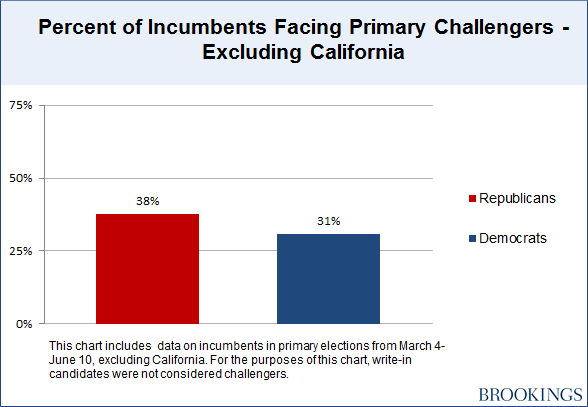

To understand this check out the next chart. If we take California out of the calculations we see that the conventional wisdom holds. The reason? It turns out that in California, a deep “blue” state where 35 of the 47 incumbents seeking re-election are Democrats, and with the new top-two primary system, 21 of them—60%—drew a Democratic or non-affiliated challenger. Often, incumbents are able to scare away primary challengers because of fundraising and name recognition. That seems not to be the case in the new primary system in California.

This might be the biggest change we’ve seen so far this year as the result of the top two system. In a traditional primary system a distant second place finish is an outright loss. No wonder that the expectation of coming in second in a primary against an incumbent is usually deemed to be not worth the trouble. Many potential challengers fail to take on incumbents. But in the new system even a distant second place finisher gets his or her name on the ballot in November which gives them the opportunity to draw votes from an electorate with higher turnout. This means a primary run is more viable and in the general election the incumbent might be more vulnerable.

This is a pretty big change for the congressional primary system. This fall we’ll be watching these California districts where two Democrats are running against each other in the general election. We’ll be curious to see whether, what is, in effect, a second primary in November, turns out to make incumbents more vulnerable than they’ve been in a long time.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Primaries Project: A Second California Primary in November?

June 10, 2014