In “The Political Economy of Discretionary Spending: Evidence from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” economists Christopher Boone of Columbia University, Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Ethan Kaplan of the University of Maryland examine the

$308 billion in discretionary spending that was a part of the American Recovery and Investment Act (ARRA), breaking out stimulus dollars by congressional district. The authors compare the amount that a district received to the characteristics of the congressperson representing that district in order to look for evidence of political influence or graft, and they don’t find any. They consider members in positions of influence, including committee leaders, long-serving representatives, and ideological moderates (potential “swing-voters”), and find no consistent evidence that these legislators received more funds. They also look at the extent to which parties directed funds for their own partisan benefit. Neither Democrats nor Republicans sent more money to swing districts where the money might be considered most effective in obtaining an electoral advantage.

Democrats on average did receive $95 more per capita than Republican districts, which could reflect an attempt by the party in power to send more money to their own constituents. Overall, the stimulus amounted to $469 per capita, with the average Republican district receiving $416 per capita as compared to $510 per capita in the average Democratic district. However, Democratic districts tend to be different from Republican districts in many ways, and Democratic districts with the same amount of employment and poverty received only $19 more than similar Republican districts, with the difference not being statistically significant.

The authors excluded from their baseline analysis all districts containing any part of a state capital, because a large majority of the money going to state-capital districts was actually disbursed to the state governments and then subsequently redistributed across the state.

Boone, Dube and Kaplan also looked at degree of party affiliation, tenure, leadership position and swing districts, finding that:

-

- Ideological moderates who voted for the bill weren’t able to use their position to get more ARRA funds;

-

- Swing districts actually received fewer ARRA funds, on average, meaning that parties didn’t target money to these districts in order to maximize their electoral chances;

-

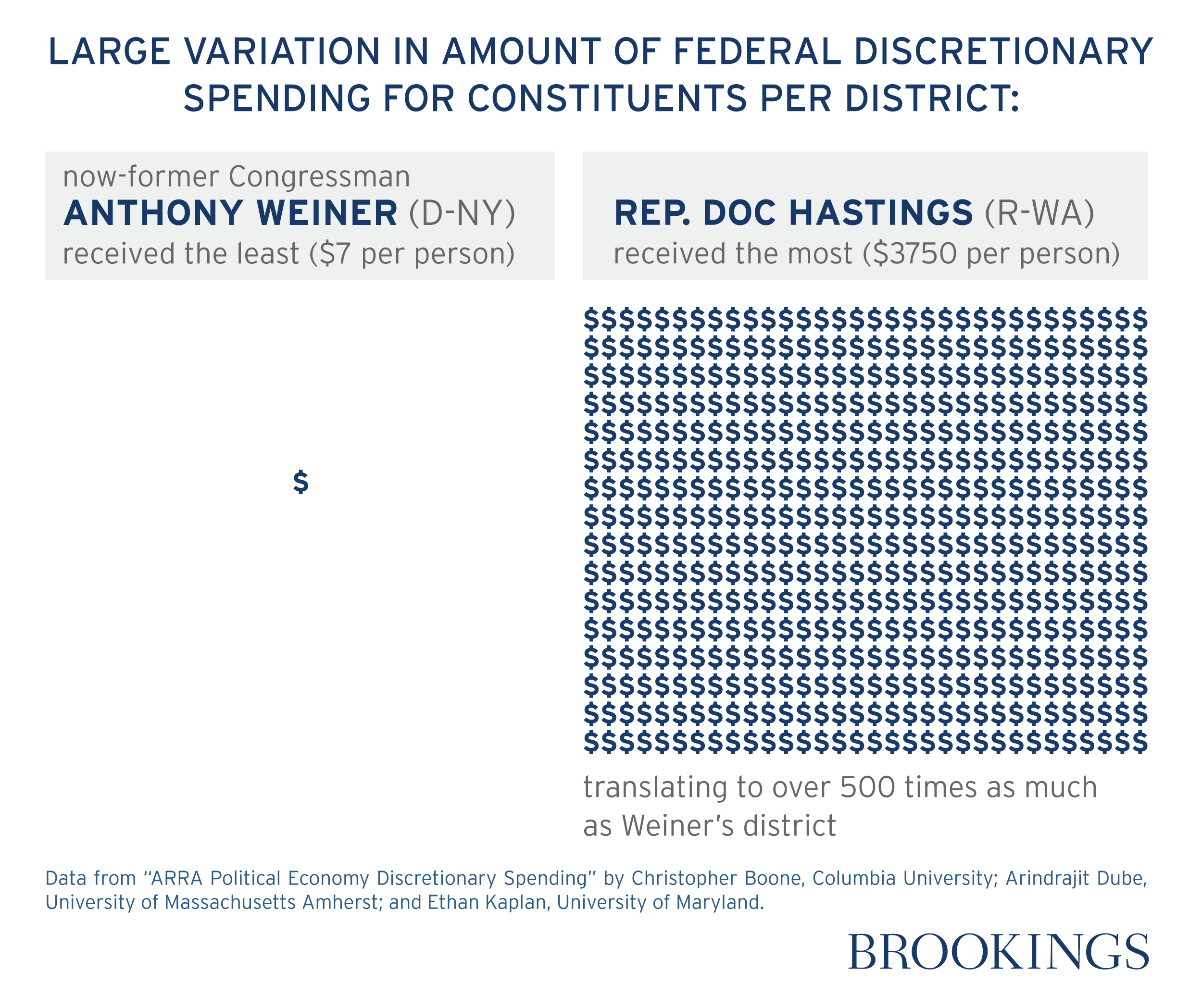

- There was large variation in the amount of project funding received across districts: now-former Congressman Anthony Weiner (D-NY) received the least amount of federal discretionary spending for his constituents ($7 per capita); Rep. Doc Hastings (R-WA) received the most, translating to over 500 times as much as Weiner’s district ($3750 per person);

-

- House leaders were generally not able to exploit their positions of power to extract more funding for their districts; among high-ranking committee members, Democrats actually received less money on average than Republicans, contrary to expectations; and

-

- Longer-serving members didn’t receive more money, either.

In addition to the lack of political targeting, the authors also find a surprising lack of cyclical targeting. Evidence suggests that stimulus funds have the biggest effects in harder-hit areas, but the authors find no relationship between the amount of money received and the severity of the economic downturn in those areas. In addition, areas that received more funding actually spent the money more slowly than areas that received less, suggesting that the lack of targeting to high unemployment areas is not attributable to targeting “shovel readiness” instead.

Though they find that districts with higher levels of unemployment received slightly fewer funds, the authors do find that districts with higher employment per resident (more urban areas with more economic activity) did receive more funds. A district with 100,000 more workers received on average $200 more per person. Increased funding also went to poorer areas: places with a 1 percentage point higher poverty rate received $16 more in stimulus dollars per person.

The authors attribute this lack of targeting to the steady development of rules governing the distribution of federal funds, put in place to reduce the infighting and graft that occurs when legislators have discretion and must bargain over the specific allocations themselves. Earlier research has found that during the Great Depression, when these rules were much less developed, stimulus spending (in the New Deal) was more geographically targeted, both politically and economically, with higher amounts going to both pro-Roosevelt areas as well as to places with higher unemployment. While the development of these legislative institutions appears to have been effective in reducing graft, it may have also hindered the ability to allocate funds in an economically optimal way.

The authors offer suggestions for ways to improve the design of fiscal stimulus, such as using “automatic stabilizers” like unemployment insurance because they appear to be well-targeted, and modifying the programs and formulas used to distribute federal spending to take into account factors like the local unemployment rate. Given that stimulus bills must be designed quickly in order to work effectively, the authors argue that politicians should begin laying the groundwork for better policies now, instead of waiting for the next crisis to hit.

“Parties did not appear to act in their own collective interest by targeting marginal districts. For the most part, politicians did not exploit their individual positions of power within the Congress to grab funds. At the same time, discretionary funds were not well targeted to high unemployment districts, and differences in “shovel readiness” as measured by the pace of spending do not appear to explain the cross-district variation in expenditures. We do find, however, that more funding went to districts with more employment per resident, which likely reflects greater economic activity. Additionally, districts with higher incidence of poverty also received somewhat greater funding.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).