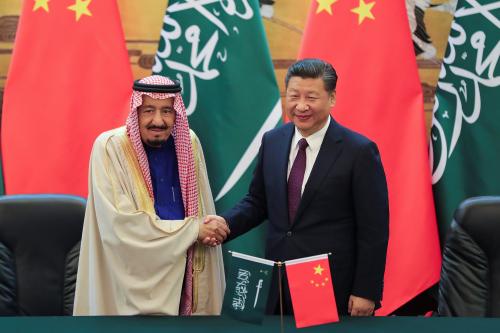

In recent weeks, the “brotherly” relationship between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia — with decades of close economic, political, and military ties — has hit a bump in the road. The immediate reason: On August 5, the one-year anniversary of India’s revocation of Kashmir’s autonomy, Pakistan’s foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, pointedly demanded that Saudi Arabia “show leadership” on the Kashmir issue. He asked Riyadh to call a special meeting of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC, which Saudi Arabia leads) to discuss it. This apparently capped months of “frustration,” according to media reports, in Islamabad at Saudi inaction on Kashmir. Qureshi also said that if Saudi Arabia did not call a meeting of OIC foreign ministers, Pakistan would be compelled to go to Muslim countries — Malaysia, Turkey, and Iran — that had voiced concern over Kashmir and stood by Pakistan’s side.

Saudi Arabia did not take kindly to this overt pressure. It immediately recalled a $1 billion loan, part of a $3 billion loan it had given Pakistan in November 2018. China stepped in to cover Pakistan with a replacement loan. A $3.2 billion Saudi oil credit facility to Pakistan has not been renewed after it expired in May this year. But while this bump in the road for the Saudi-Pakistan relationship is notable, it is premature to conclude that it will be long-lasting.

The backstory

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have long been close. The kingdom has helped bail out Pakistan’s economy at multiple points. Saudi influence in Pakistan has increased over the decades, with Saudi funding for madrassahs leading to the import of Wahhabi Islam into the country. At the same time, Pakistan also maintains a good relationship with Iran, in part because of its large Shiite minority (with Saudi Arabia taking precedence if Pakistan is forced to choose between the two). The desire to balance the relationship with Iran was one reason that Pakistan did not send troops to Yemen, per Saudi Arabia’s request, in 2015 — despite having just received a large Saudi loan. In recent months, Pakistan has stepped up this balancing act, offering and trying to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia last fall. Prime Minister Imran Khan has spoken often of a foreign policy that rests on a solid relationship with all Muslim countries.

Last fall, Khan announced that he would attend Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur summit for Muslim countries to be held in December, which Saudi rivals Iran, Turkey, and Qatar would also attend (and to which Saudi Arabia was not invited). This reportedly irked Saudi Arabia, and after Khan visited the kingdom, Pakistan abruptly withdrew from the Kuala Lumpur summit, ostensibly due to Saudi pressure. Saudi Arabia officially denies pressuring Pakistan, but in his remarks this month, Qureshi implied as much when he suggested that Pakistan expected Saudi Arabia to call an OIC meeting given that Pakistan had skipped the Kuala Lumpur summit.

Saudi Arabia has not shown any interest in calling a special OIC meeting on Kashmir. The reticence is explained by economics and the kingdom’s close and growing ties with India: Bilateral trade between India and Saudi Arabia is $27 billion annually, whereas Pakistan-Saudi trade is just $3.6 billion. The implication, then, according to analysts, is that Saudi Arabia will not want to anger India by asserting itself on Kashmir. (Saudi Arabia, it should be noted, has also remained silent on China’s mistreatment of its Muslim minority Uighur population.)

A minister gone rogue or a concerted approach?

Many in Pakistan were stunned by Qureshi’s recent remarks — which were out of character with anything Pakistan has officially said to Saudi Arabia in the past — and opposition parties roundly condemned them. Some wondered whether Qureshi spoke out unilaterally, but a number of factors (beyond Qureshi’s deliberative nature) suggest that he may not have acted on his own. It’s not how Khan’s government, which acts in concert with the military, conducts its foreign policy — and especially not on anything to do with Kashmir. There was no immediate rollback from the Foreign Office, which stood by the remarks; nor was Qureshi asked to issue a clarification or apology, as in the past when government members have acted on their own (for example, in September 2018, when one of Khan’s advisers said that China-Pakistan Economic Corridor loans had not been negotiated fairly). It seems unlikely that Qureshi acted without explicit approval from Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Instead, his interview may have been a risky pressure tactic on Saudi Arabia that backfired.

A military trip to the kingdom

Pakistan has sought to downplay the Saudi response and the recall of the loan. But soon after Pakistan paid back the loan, it was announced that army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa would visit Saudi Arabia on August 17. The trip was billed as pre-planned, and for military-to-military purposes. Before the trip, the director general of the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), the military’s PR arm, sought to dispel the idea of a rift, saying the relationship with Saudi Arabia “is historic, very important and excellent, and will remain excellent. There should be no doubt about it.” He also said Saudi “centrality” to the Muslim world was clear.

If the army chief’s visit was a damage-control trip, it’s unclear that it worked. Details were kept quiet, and it played out as it was billed, for military-to-military meetings. There was no official press release from the ISPR, and Riyadh released a spare statement. Bajwa met the Saudi chief of general staff and the vice minister of defense, Khalid bin Salman. The director general of the Inter-Services Intelligence, Pakistan’s spy agency, accompanied him. It seems Bajwa did not meet Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), which is significant. Bajwa and MBS had met on the army chief’s previous visits to the kingdom, and on MBS’ visit to Islamabad last year. (MBS has had a close relationship with Khan as well, who was one of the few leaders who stood by him after the killing of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi. But so did Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and MBS also visited Delhi after his Islamabad trip last year.) All in all, there was no big rapprochement.

Looking ahead

If Pakistan felt snubbed by how the army chief’s visit went, it has refused to acknowledged it. In an interview last week, Khan sought to dispel the sense of a rift. Yet he also seemed resigned to the idea that Saudi Arabia would not act the way Pakistan wanted on Kashmir going forward: “Saudi has its own foreign policy. We shouldn’t think that because we want something Saudi will do just that.”

What’s clear is that Pakistan’s bold move — concerted or not — didn’t work, and the Saudi response shows Pakistan that it cannot be the “brother” Pakistan wants it to be, at least on Kashmir. The whole episode only serves to reinforce China’s status as Pakistan’s closest partner — its “all-weather” friend, as Khan repeated in his interview last week. (Foreign Minister Qureshi was in China for two days last week, for the second round of the China-Pakistan Foreign Ministers’ Strategic Dialogue, and the two countries reaffirmed their relationship as “iron brothers.”)

It’s also clear that Pakistan may have to look to other Muslim countries for the support it wants on Kashmir. Turkey, Malaysia, Iran, and Qatar seem willing to step up. But the question is whether Saudi Arabia will let Pakistan move closer to these countries. The kingdom has Pakistan in a bit of a box, and economics on its side. Pakistan can potentially rely on China to cover some Saudi loans, as it did — but likely not all, and Pakistan also relies on remittances from more than 2 million Pakistanis who have traveled to Saudi Arabia for work. It simply cannot afford to alienate the kingdom. Sure enough, late last week, the Foreign Office reaffirmed Pakistan’s commitment to the OIC and recounted actions it had taken in the past on Kashmir.

For now, Pakistan may have to lay low on the issue of Kashmir’s autonomy. And while there may be cracks in the friendship with Saudi Arabia, it is premature to expect any big realignments.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Pakistan-Saudi Arabia relationship hits a bump in the road

What happened, and what lies ahead

August 24, 2020