Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

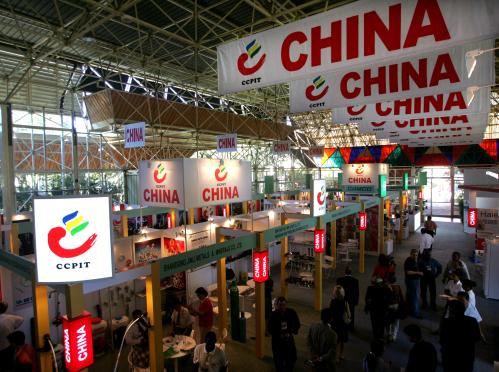

In the past 15 years, China has become the most significant new economic actor in Latin America and the Caribbean. China-Latin America trade increased from almost negligible in 1990, to $10 billion in 2000, to $270 billion in 2012, although the largest portion of this exchange takes place between South America and China. This raises important and legitimate questions about what kind of influence China has had on the region’s economic and political development.

In the past 15 years, China has become the most significant new economic actor in Latin America and the Caribbean. China-Latin America trade increased from almost negligible in 1990, to $10 billion in 2000, to $270 billion in 2012, although the largest portion of this exchange takes place between South America and China. This raises important and legitimate questions about what kind of influence China has had on the region’s economic and political development.

Some analysts have expressed alarm at the growing level of Chinese trade, loans, and investment in Latin America, often on favorable terms with less conditionality than traditional Western powers. At best, China’s economic behavior may enable bad policy choices by Latin American states; at worst, it may represent a concerted strategy by China to achieve political influence in Latin America, challenging or supplanting U.S. hegemony. A more benign interpretation suggests that China’s role in the region has been positive. Chinese demand for Latin America’s commodities undeniably has helped drive the economic boom of the past decade that doubled the size of Latin America’s middle class and dramatically reduced poverty. Some even speculate that China’s growing interests in positive, stable returns may lead it to converge on Western models of rules-based investment and development.

Ted Piccone reflects on the broad geopolitical implications of China’s role in Latin America, exploring whether increased economic connection with Latin American states is a further indication of a China more assertively challenging a Western or U.S.-led international order. He asserts that:

- The China-Latin America economic relationship has had direct effects on some Latin American states’ willingness to join China in challenging a U.S.-led liberal world order—typically when their interests already align;

- Latin American states appear to calibrate their alignment with Beijing and Washington based in part on economic ties and integration with each great power, in part on their ideologies, and in part based on the specific issue under consideration;

- For now, China’s rise has not unduly harmed core U.S. national security interests in the Western Hemisphere, but it has challenged U.S. influence and warrants continued attention.