Claudia Swanson knew that child care spots for infants were scarce in her rural Minnesota community. So she got on waitlists early in her pregnancy in 2020, and over a year later, secured a day care spot for her daughter—only for the center to unexpectedly shut down a month later due to a lack of funds.

“It was devastating,” Swanson told us. “And very scary. I lost hope.” Every day care she called was full. She had to quit her job as a social services case manager, and nearly lost her house.

“I went from being a social services case manager and a leader to becoming a client myself,” said Swanson. After being out of work for six months, she finally secured a high-quality, dependable child care spot, providing the security and support she needed. “The day that my daughter started day care is the day I went back to work,” she said. Today, Swanson is a head chef and owns a catering company that employs several staff members.

A sudden loss of child care can be destabilizing, distressing, and make it very difficult to hold down a job. Access to affordable and reliable child care is one reason that women with children are able to work.

In 2021, the White House and Congress helped steady the child care sector, which has always been unstable, but was especially hard-hit during the pandemic. The American Rescue Plan Act sent a one-time infusion of $24 billion in child care stabilization funds to states, which helped more than 200,000 child care providers keep their doors open. Yet these funds must be spent by states by September 30, creating a funding cliff for state support to the child care sector.

Investing in child care matters because right now, women have made impressive gains in the labor market. But if Congress fails to allocate additional funding for the sector by the end of the month, work will be that much more difficult for millions of parents.

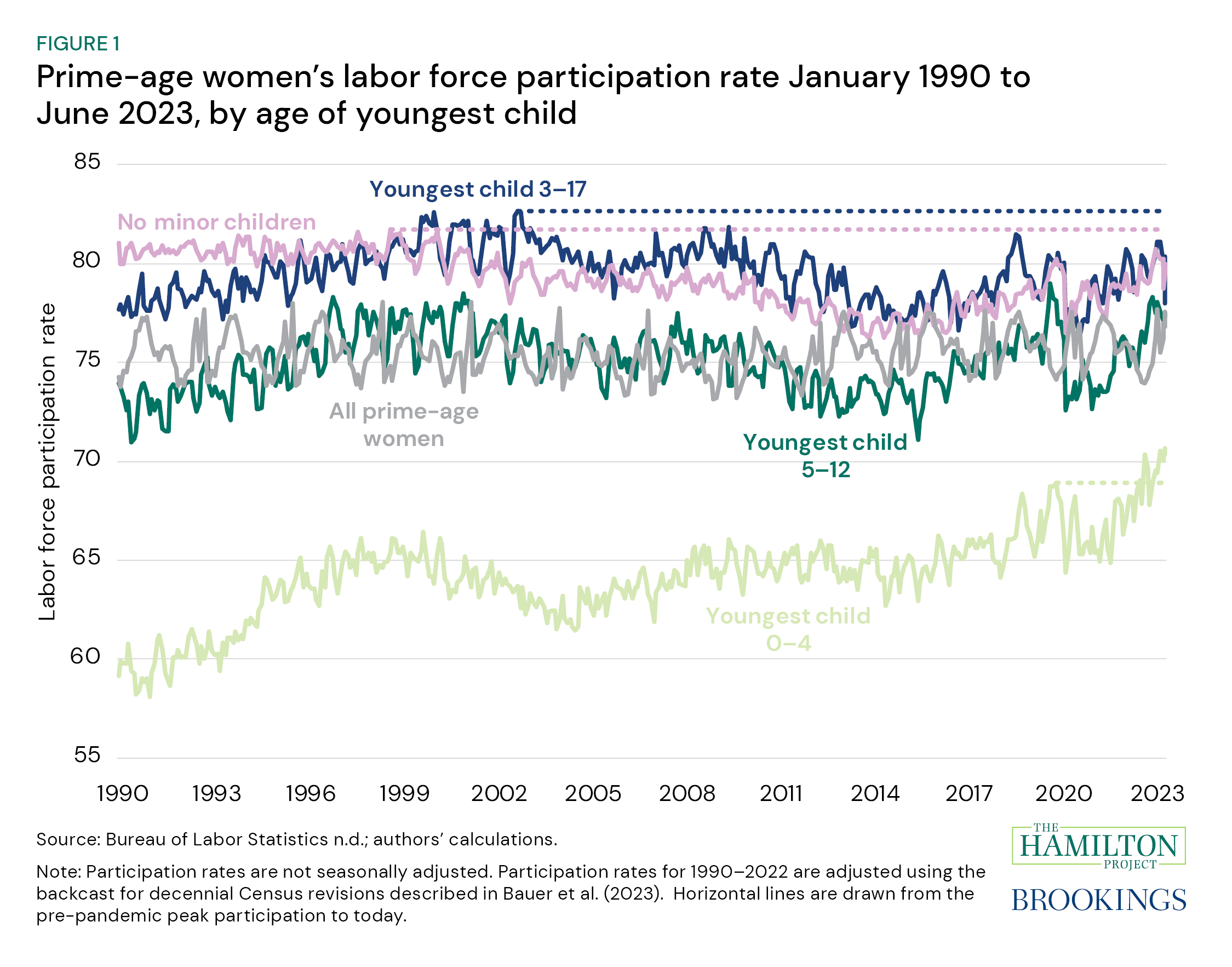

After living through pandemic-era job losses, school closures, and caregiving crises, women between the ages of 25 and 54 have lifted their labor force participation rate to its highest level ever: approximately 78%. Incredibly, mothers with young children under the age of five are leading the way; about 70% of them are now in the labor force—an increase of 5 percentage points over the decade before the pandemic (Figure 1).

Record high participation isn’t just an historic milestone for women—it’s critical for the economy. Women are stepping up for all of us at a time when the economy is missing workers and needs to draw more people into the labor force to grow. The labor force is smaller because of the pandemic, but demand is quite high. Increasing participation allows the economy to grow while easing pressure on inflation.

Women’s participation gains have driven the economic recovery. But that recovery is fragile, and built on an unstable, patchwork child care system. If Congress fails to extend these stabilization funds, the Century Foundation predicts that 70,000 child care facilities could shutter and 3.2 million children could lose child care.

Courtney Greiner runs a child care center in Minnesota. Like many child care center directors, she struggles to stay afloat with high staff costs and low profit margins. The funds Greiner’s center received from the state and from the federal stabilization fund have allowed her to retain employees without raising rates at a time when child care is already unaffordable to most American families. She’s proud to be able to provide for families in her community, but admits that “without additional money, I wouldn’t be able to keep my center open.”

Ending funding to the child care sector could reverse the gains we see now. Already, parents struggle to find child care. Waitlists can stretch for years, and the child care workforce is more than 10% smaller than it was at the start of the pandemic, even as more mothers have gone to work. It is little wonder that one-fifth of mothers with young children who wanted a job in 2023 weren’t looking for one due to child-care-related concerns, according to our analysis of Census Bureau data.

For some mothers of young children, the rise of telework has supported flexibility to balance work and family, including managing a disruption in child care (at least temporarily). But telework cannot absorb the consequences of a collapse in the sector. This is something we, the authors of this piece, understand personally—and not just from during the worst of the pandemic. This year, one of us unexpectedly lost child care for three young children. Even with the flexibilities of telework, it prompted a make-or-break confession to a supervisor: “If I can’t find another child care arrangement that works, I cannot keep doing this job.”

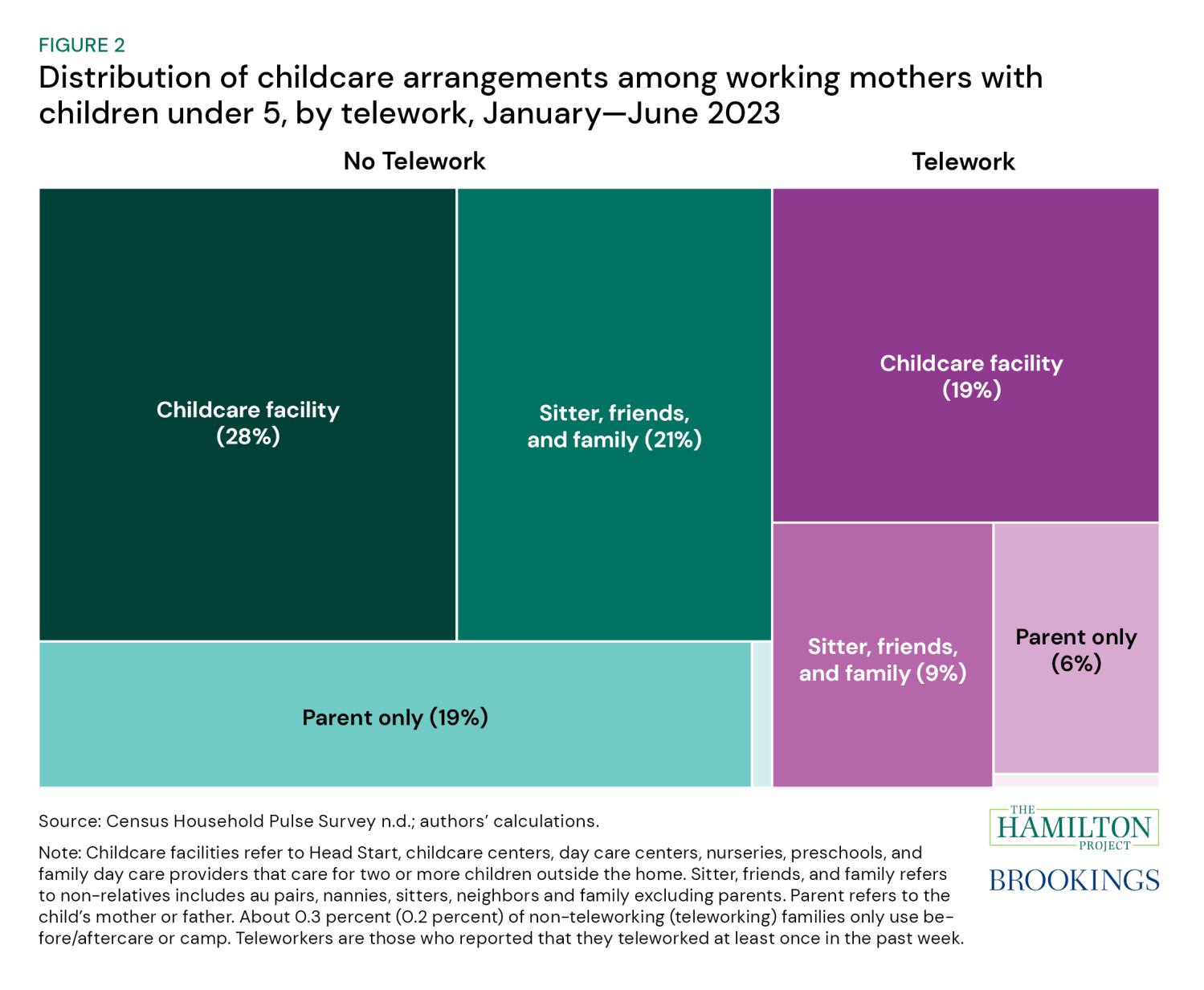

Not everyone can telework; two-thirds of working mothers with young children don’t. For many of these women—among them, many low-income working mothers and working mothers of color—there is no wiggle room to manage a lapse in child care, even temporarily. And teleworking women need child care too.

Figure 2 shows child care arrangements for working prime-age mothers with young children, categorized by whether or not they report having teleworked at least once in the prior week. While many families use more than one child care arrangement, this figure represents exclusive categories in the following order: child care facilities; sitter, friends, and family; parent only; and before/after care or camp. For example, this means that if a family uses both child care facilities and parental care, they are categorized as using child care facilities.

This analysis shows that half of all working mothers of young children at least partially rely on child care facilities. While they are only one way that parents get care, 55% of teleworking mothers with young children and 43% of non-teleworking mothers with young children use child care facilities. Critically, just 6% of working mothers with young children telework while only using parental care.

Since 2020, labor market conditions and policy have made working easier and more rewarding for mothers of young children, so many more have chosen to participate in the labor force. But now, this historic growth in participation that mothers with young children have only just achieved is at risk.

Much is on the line for these working mothers and others who want to work: a job, health insurance, retirement savings, and the income a family relies on to support themselves and save for tomorrow.

Congress must proactively invest in today’s—and tomorrow’s—workforce. Earlier this month, we learned that when Congress allowed the enhanced Child Tax Credit to lapse after 2021, child poverty more than doubled. If Congress does nothing about child care stabilization by September 30, millions of working parents, and the economy as a whole, would be the collateral damage.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

We thank Leigh Balon, Alan Berube, Chloe East, Wendy Edelberg, Este Griffith, Olivia Howard, Aaron Sojourner, and Marie Wilken for their help and helpful comments. We deeply appreciate the child care providers (April Macklin and Courtney Greiner) and mothers (Claudia Swanson and Leah Budnik) who shared their stories with us, and Lydia Boerboom, Moriah Macklin, Natalie Nenew, and Rachel Schumacher for their timely introductions. Olivia Howard and Isabelle Pula provided exceptional research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The coming end of federal child care funding threatens working mothers’ gains

September 26, 2023