How are your New Year’s resolutions going? You know the ones to eat less, exercise regularly, and save more money? If you are struggling, you are not alone. By the end of January, about one-third of resolvers will have given up; six months later, that number is likely to increase to 56 percent, according to one estimate.

We will have a lot more success if we recognize our own frailties and lock ourselves into behaviors consistent with our goals: giving away all the chocolate truffles we received as holiday gifts, signing up for classes at the local gym, and enrolling in an automatic savings plan. One study found, for example, that making enrollment in a 401(k) plan automatic (with an opt-out provision) caused participation to more than double (from 37 to 86 percent).

Family Planning – a Resolution with Bigger Consequences

One of the biggest decisions we make in life is whether and when to start a family. It has something in common with making New Year’s resolutions, since an accidental pregnancy is one of many instances in which we fail to follow through on our good intentions. Children born to parents who were planning for a child do better in life than those who arrive by accident.

Yet about half of all pregnancies in America are unplanned and almost three-quarters of pregnancies occur among single women under 30. Rates of unplanned pregnancy are especially high among the least advantaged. According to the answers given by new mothers on government surveys, most of these pregnancies are either unwanted or seriously mistimed. These pregnancies are not only inconsistent with women’s own preferences— they also limit the life prospects of their children.

Prevention is therefore of paramount importance. The introduction of the birth control pill and the legalization of abortion in the 1960s and 1970s enabled women to better control their fertility, and therefore to substantially better educational outcomes and higher incomes for their children, according to a careful study by Martha Bailey at the University of Michigan.

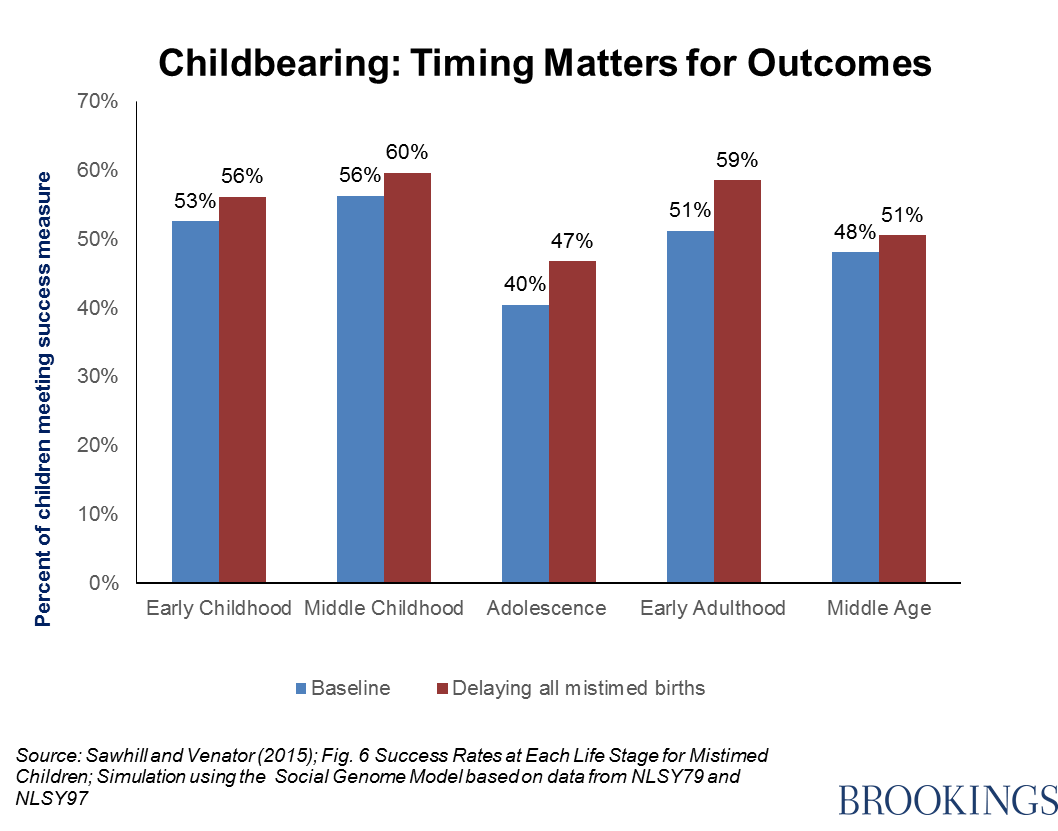

We should celebrate this progress; but unplanned pregnancies and births are still far too common. New research by me and Joanna Venator reinforces this point. We simulate the effects of aligning women’s fertility behavior with their intentions, and show that helping women to delay births until they themselves say they would prefer to have a child can improve child well-being, including their chances of graduating from college and their income in middle age:

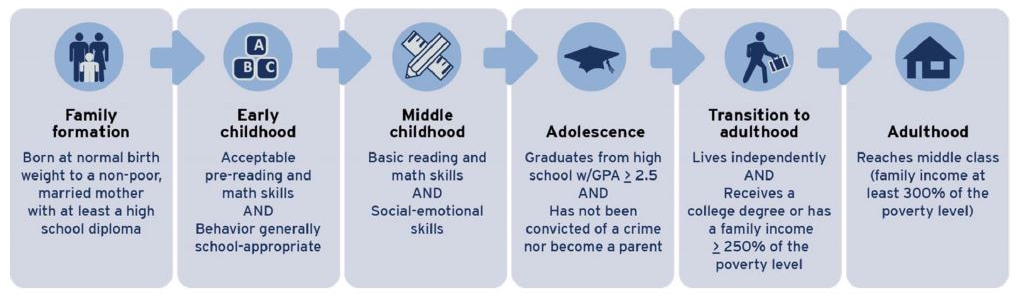

The success measures used in the above graph are the same as used in our Social Genome Model:

LARCS as Commitment Devices

Now let’s go back to New Year’s resolutions. Is there an analogous commitment device that could reduce unplanned births and improve child outcomes in the process? There is. It’s called long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). It includes the IUD and the implant. It commits the user to not having a child until she and her partner really want one – that is, until they opt out of the automatic protection a LARC provides. The problem is that too few women or their partners know about LARCs, too few doctors are trained in their use, and the upfront costs of the devices are high (at least $500). Over the longer term, LARCs cost less than the pill, are now deemed safe (unlike in an earlier era when they caused pelvic infections and even death), and are far more effective at preventing an unplanned pregnancy than the pill or a condom.

The effectiveness of LARCs has nothing to do with the devices themselves and everything to do with the fact that they change the default in ways that protect us from our own frailties (such as forgetting to take a pill or not using a condom in the heat of the moment). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists describes LARCs as “the most effective forms of reversible birth control available” and advises that they should be considered “first-line contraceptive methods and encouraged as options for most women.” At the end of five years, the chances of pregnancy for a woman using a LARC are trivial, whereas they are 63 percent for those relying on condoms and 38 percent for those using the pill. (These are average failure rates; some people are more consistent users than others). Where LARCs have been made available for free, with good counselling on their safety and effectiveness, such as in privately-funded demonstration programs in Colorado and in St. Louis, unplanned pregnancy rates have dropped sharply and so have abortion rates.

If we want to provide better life chances for the next generation and reduce child poverty, here’s a simple and inexpensive way of doing so. If you are a health care provider, resolve to make sure your staff is well trained to provide the best counselling and services, including LARCs. If you are a sexually active young adult not yet ready to have a child, resolve to get a LARC. And if you are an elected official or a citizen, resolve to stop fighting over whether women should have the ability to control when and with whom they get pregnant. It is not just their lives but also those of their children that hang in the balance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Best New Year’s Resolution: Intentional Childbearing

January 26, 2015