This essay is part of “Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

Inequality was bad and the COVID-19 pandemic is making it worse. The immediate priority is to protect the disadvantaged and the vulnerable from the health and economic impacts of the crisis. But policies must also address the deeper, structural drivers of the rise in inequality.

Inequality was bad and the COVID-19 pandemic is making it worse. The immediate priority is to protect the disadvantaged and the vulnerable from the health and economic impacts of the crisis. But policies must also address the deeper, structural drivers of the rise in inequality.

The issue

“The COVID-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history.”1The pandemic has thrown into stark relief the high and rising economic inequality in the United States and elsewhere. The costs of the pandemic are being borne disproportionately by poorer segments of society. Low-income populations are more exposed to the health risks and more likely to experience job losses and declines in well-being. These effects are even more concentrated in economically disadvantaged minorities. The pandemic is not only exacerbated by the deprivations and vulnerabilities of those left behind by rising inequality but its fallout is pushing inequality higher.2

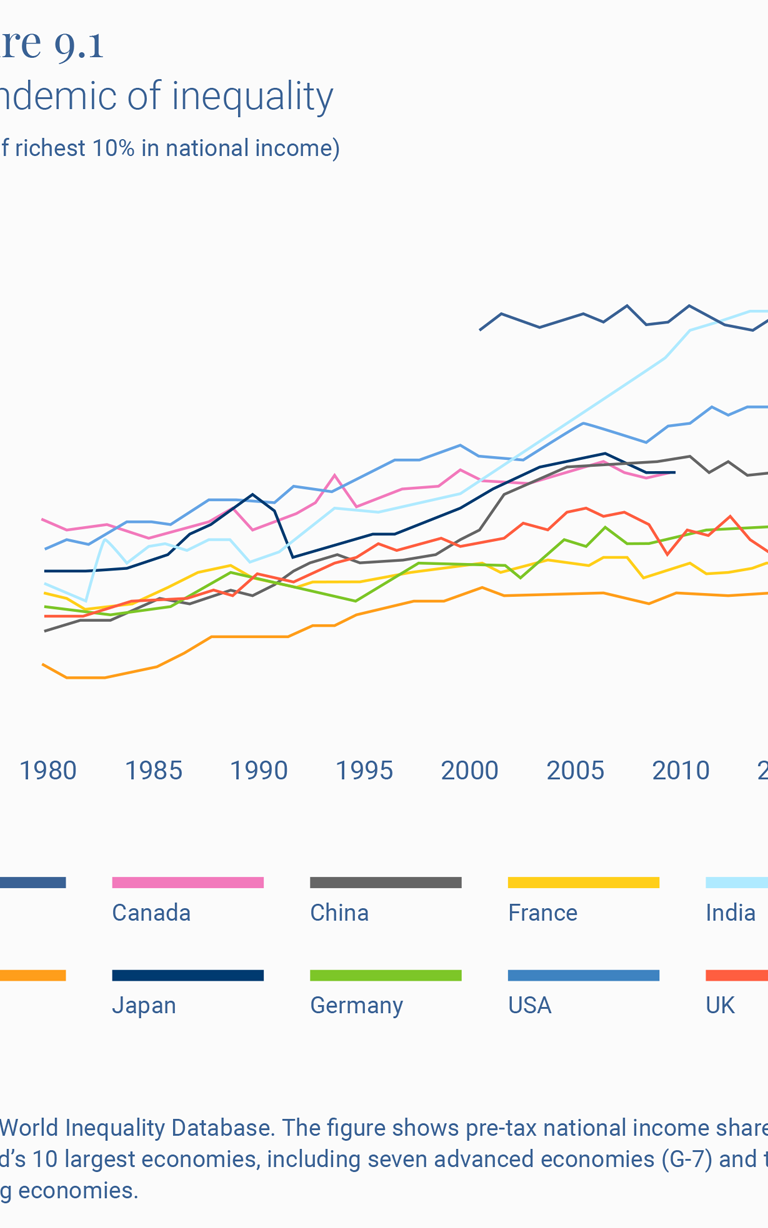

Income and wealth inequality has risen in practically all major advanced economies over the past two to three decades. It has risen particularly sharply in the United States. The increase in inequality has been especially marked at the top end of the income distribution (Figure 9.1). Those with middle-class incomes have been squeezed and the typical worker has seen largely stagnant real wages over long periods. Intergenerational economic mobility has declined. Income distribution trends are more mixed in emerging economies but many of them have also experienced rising inequality, including some major emerging economies such as China and India.

Rising inequality is a major fault line of our time, with adverse economic, social, and political consequences. It has depressed economic growth by dampening aggregate demand and slowing productivity growth. It has stoked social discontent, political polarization, and populist nationalism. And as the pandemic has revealed, it has increased societal and economic fragility to shocks.

The pandemic is not only exacerbated by the deprivations and vulnerabilities of those left behind by rising inequality but its fallout is pushing inequality higher.

The ideas

What does research say about why inequality is rising? Many factors affect income distribution but research has increasingly focused on technological change as a key driver of the rise in inequality observed in recent decades.3 Digital technologies have been transforming markets and how we work and do business, and the latest advances in artificial intelligence are driving the digital revolution further. The benefits of this technological transformation have been shared highly unequally.

Inequalities have increased between firms and between workers. Firms at the technological frontier have broken away from the rest, acquiring dominance in increasingly concentrated markets and capturing the lion’s share of profits. Increasing automation of low- to middle-skill tasks has shifted labor demand toward higher-level skills, hurting wages and jobs at the lower end of the skill spectrum. With the new technologies favoring capital, winner-take-all business outcomes, and higher-level skills, the distribution of both capital and labor income has become more unequal, and income has shifted from labor to capital.

The COVID-19 pandemic is reinforcing these inequality-increasing dynamics. It is causing the digital transformation of production, commerce, and work to accelerate.4 While smaller firms struggle, large technologically advanced firms are further increasing market shares, fortifying the shift toward more oligopolistic, less competitive markets.5 Increased automation and telework are further tilting labor markets against low-skilled, low-wage workers.6 Industries with business models heavily reliant on human contact and low-skilled workforce are hit especially hard.

Globalization also has contributed to rising inequality within economies—although technological change has been the more dominant factor. But it has been a force for reduced inequality between economies. Expanding global supply chains have been a major spur to economic growth in emerging economies, enabling them to narrow the income gap with advanced economies. The pandemic could disrupt this economic convergence by stoking the backlash against globalization and provoking nationalist trade policy responses, including reshoring of production. This would add to the challenges emerging economies face as increasing automation necessitates search for new growth models less reliant on low skill, low-wage labor as the source of comparative advantage.

A weakening redistributive role of the state also has been a factor pushing inequality higher. As shifts in product and labor markets caused by technological change—and globalization—drove inequality of market incomes within economies higher, the role of the state in alleviating market-income inequality through taxes and transfers diminished. In OECD economies, taxes and transfers typically kept disposable-income inequality one-fifth to one-quarter lower than market-income inequality. In recent years, the role of fiscal redistribution in offsetting the rise in market-income inequality has shrunk because of reduced progressivity of personal income taxes, lower taxes on capital, and tighter spending on social programs.

A weakening redistributive role of the state also has been a factor pushing inequality higher.

The way forward

Is rising inequality an inevitable consequence of today’s technology-driven economic transformations—and globalization? The answer is no. Policies have been slow to respond to the challenges of change. With better, more responsive policies, more inclusive economic outcomes are possible.

The first order of business is to contain the pandemic and address its immediate health and economic consequences that disproportionately hurt the less well-off. Countries have responded in varying degrees by taking preventive measures against the pandemic, shoring up health systems, strengthening safety nets, and implementing policies to cushion the impact on jobs and economic activity. The more successful these actions are in protecting the vulnerable and supporting economic recovery, the less will be the direct impact of the crisis in worsening existing inequalities.

Beyond these immediate actions is a longer-term agenda to address the underlying drivers of the secular rise in inequality. Policies to reduce inequality are often seen narrowly in terms of redistribution―tax and transfer policies. This is of course an important element, especially given the erosion of the state’s redistributive role. In particular, systems for taxing income and wealth should be bolstered in light of the new distributional dynamics. But there is a much broader policy agenda of “predistribution” that can make the growth process itself more inclusive.7

A core part of this broader agenda is to better harness the potential of technological transformation to foster more inclusive economic growth:

- As technology transforms the world of business, policies and institutions governing markets must keep pace. Competition policies should be revamped for the digital age to ensure that markets provide an open and level playing field for firms, keep competition strong, and check the growth of monopolistic structures. This includes regulatory reform and stronger antitrust enforcement. New issues revolving around data (the lifeblood of the new economy) and market concentration resulting from tech giants that resemble natural or quasi-natural monopolies must be addressed. New thinking is needed on ways to broaden capital ownership and reform corporate governance to reflect wider stakeholder interests.

- In an increasingly knowledge-driven economy, the innovation ecosystem should be improved to promote wider diffusion of technologies embodying new knowledge. Reform of patent regimes and more effective use of public investment and tax policies on research and development can help “democratize” the innovation system so that it serves broader economic and social goals rather than narrow interests of a small group of investors.8 Biases in the tax system favoring capital relative to labor that create incentives toward “excessive automation”—that destroys jobs without enhancing productivity—should be corrected.9

- The foundation of digital infrastructure and digital literacy must be strengthened to expand access to new opportunities. The digital divide remains wide between groups within economies, and is wider still between economies at different levels of development.

- Investment in education and training must be boosted, with stronger programs for worker upskilling, reskilling, and lifelong learning that respond to shifts in the demand for skills. This will require innovation in the content, delivery, and financing of (re)training, including new models of public-private partnerships. Persistent inequalities in access to education and training must be addressed. While gaps in basic capabilities have narrowed, those in higher-level capabilities that will drive success in the 21st century have widened.10

- Labor market policies should shift to a more forward-looking focus on improving workers’ mobility, helping them to move to new and better jobs rather than seeking to protect existing jobs being rendered obsolete by changing technology. The pandemic has exposed weaknesses in social safety nets. Social protection systems should be strengthened, indeed overhauled. Traditionally based on formal long-term employer-employee relationships, they should be adapted to a job market with more frequent job transitions and more diverse work arrangements. Social contracts need to realign with the changing economy and the nature of work.

At the international level, not only must past gains in establishing a rules-based international trading system be shielded from the rise of protectionist sentiment, new disciplines need to be devised for the next phase of globalization led by digital flows to ensure open access and fair competition. International cooperation on tax matters becomes even more important in view of the new tax challenges of the digital economy.

Inevitably, major economic reform is politically complex. Today’s elevated political divisiveness adds to the challenges. One thing reform should not be paralyzed by, however, is continued trite debates about conflicts between growth and equality. Research has increasingly shown this to be a false dichotomy.11 Crises can shift the political setting for reform. The fault lines exposed by the pandemic can be a catalyst for change.

-

Footnotes

- Heather Long, Andrew Van Dam, Alyssa Fowers and Leslie Shapiro, “The covid-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history,” The Washington Post, September 30, 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/business/coronavirus-recession-equality/.

- Heather Boushey and Somin Park, “The Coronavirus Recession and Economic Inequality: A Roadmap to Recovery and Long-Term Structural Change,” Center for Equitable Growth, August 2020; Brown, Caitlin, and Martin Ravallion, “Inequality and the Coronavirus: Socioeconomic Covariates of Behavioral Responses and Viral Outcomes Across U.S. Counties,” NBER Working Paper 27549, July 2020; and Furceri, Davide, Prakash Loungani, Jonathan Ostry, and Pietro Pizzuto, “Will COVID-19 Affect Inequality? Evidence from Past Pandemics,” Covid Economics 12: 138-57, May 2020.

- Zia Qureshi, “Inequality in the Digital Era,” in Work in the Age of Data, BBVA, Madrid, February 2020.

- Alex Chernoff and Casey Warman, “COVID-19 and Implications for Automation,” NBER Working Paper 27249, July 2020

- Nancy L. Rose, “Will Competition be Another COVID-19 Casualty?,” The Hamilton Project, Brookings, July 2020.

- David Autor, “The Nature of Work after the COVID Crisis: Too Few Low-Wage Jobs,” The Hamilton Project, Brookings, July 2020.

- Jacob Hacker, “The Institutional Foundations of Middle Class Democracy,” Policy Network, May 2011.

- Dani Rodrik, “Democratizing Innovation,” Project Syndicate, August 11, 2020.

- Daron Acemoglu, Andrea Manera, and Pascual Restrepo, “Does the U.S. Tax Code Favor Automation?,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2020.

- United Nations, Human Development Report 2019: Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today – Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century, New York.

- Brookings Institution and Chumir Foundation, Productive Equity: The Twin Challenges of Reviving Productivity and Reducing Inequality, Report, 2019, Washington, DC; and OECD, The Productivity-Inclusiveness Nexus, 2018, Paris.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).