This viewpoint is part of Foresight Africa 2024.

Democratic backsliding via military takeovers, electoral rigging, and unlawful constitutional amendments has notably increased in Africa over the last decade. However, subnational democracy remains relatively robust, and mayors are increasingly engaged in policy experimentation and tapping into global networks to tackle major development issues, such as climate change and food security. In fact, political decentralization—or the selection of local leaders via elections—has dramatically spread since the early 1990s when many African countries began pursuing twin democracy and decentralization initiatives. Between 1990 and 2017, the share of African countries with elected local councils grew from 28% to 59%.1 Several countries, including Madagascar, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Zambia, allow citizens to directly elect their mayors rather than having them indirectly chosen by elected council members or appointed by presidents. Moreover, a commitment to some form of decentralization—which involves the transfer of powers from national governments to local authorities—is now a common feature in most African countries’ constitutions. Looking ahead to 2024, strengthening local governance will play a key role in helping improve leaders’ accountability to their constituencies and improving support for broader democracy in the region.

Africa’s local leaders at the forefront of development challenges

Several major development initiatives give Africa’s local leaders, especially mayors, greater prominence. These include the localization efforts around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and specifically SDG 11 on Sustainable Cities and Communities. Climate change is a particular threat to Africa’s low-lying coastal cities, which has galvanized a dozen mayors of major African cities to join the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. With rapid urbanization, feeding growing populations in Africa’s cities with healthy, affordable, and safe food is an equally important concern. As such, many mayors have signed on to the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. In places like Freetown, Mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr has even been working to deliver the “Healthy Food to All” initiative to improve diets and food consumption. More broadly, mayors in a dozen African countries committed to the Global Mayors Declaration on Democracy, which was released during the 2023 Democracy Summit and expressed a commitment to fight back against illiberal forces, support free and fair elections, and defend against attacks on free expression. Many countries now also have robust associations of local authorities who tap into these global networks to elevate their own efforts to increase their autonomy to make policy decisions for the local communities that they oversee. For instance, the Local Government Association of Zambia has been cited as a global leader in conducting a Voluntary Subnational Review of the state of SDG localization within Zambia and has emphasized that local government can be a critical avenue for increasing democracy in the country.2

Looking ahead to 2024, strengthening local governance will play a key role in helping improve leaders’ accountability to their constituencies and improving support for broader democracy in the region.

The dangers and disappointments of local government

Yet for all their potential, local governments face a variety of challenges on the continent. In South Africa, for instance, the number of powers that municipalities have, including over job creation and decisions over procurement contracts, make councilors vulnerable to criminal gangs. Political violence targeting local officials has escalated in recent years, and between 2000-2018, 89 local councilors were killed.3 Coalition-governed councils in some parts of the country have exacerbated the violence, which is expected to get worse as the 2024 national elections loom and as the ruling African National Congress is anticipated to fail to get a majority of votes.4 Intra-elite fighting in local government also leads to challenges of service provision. Johannesburg, for instance, has had six mayors since the country’s 2021 local elections. In Harare, Zimbabwe, intra-party fighting on the city council similarly has resulted in frequent mayoral turnover.

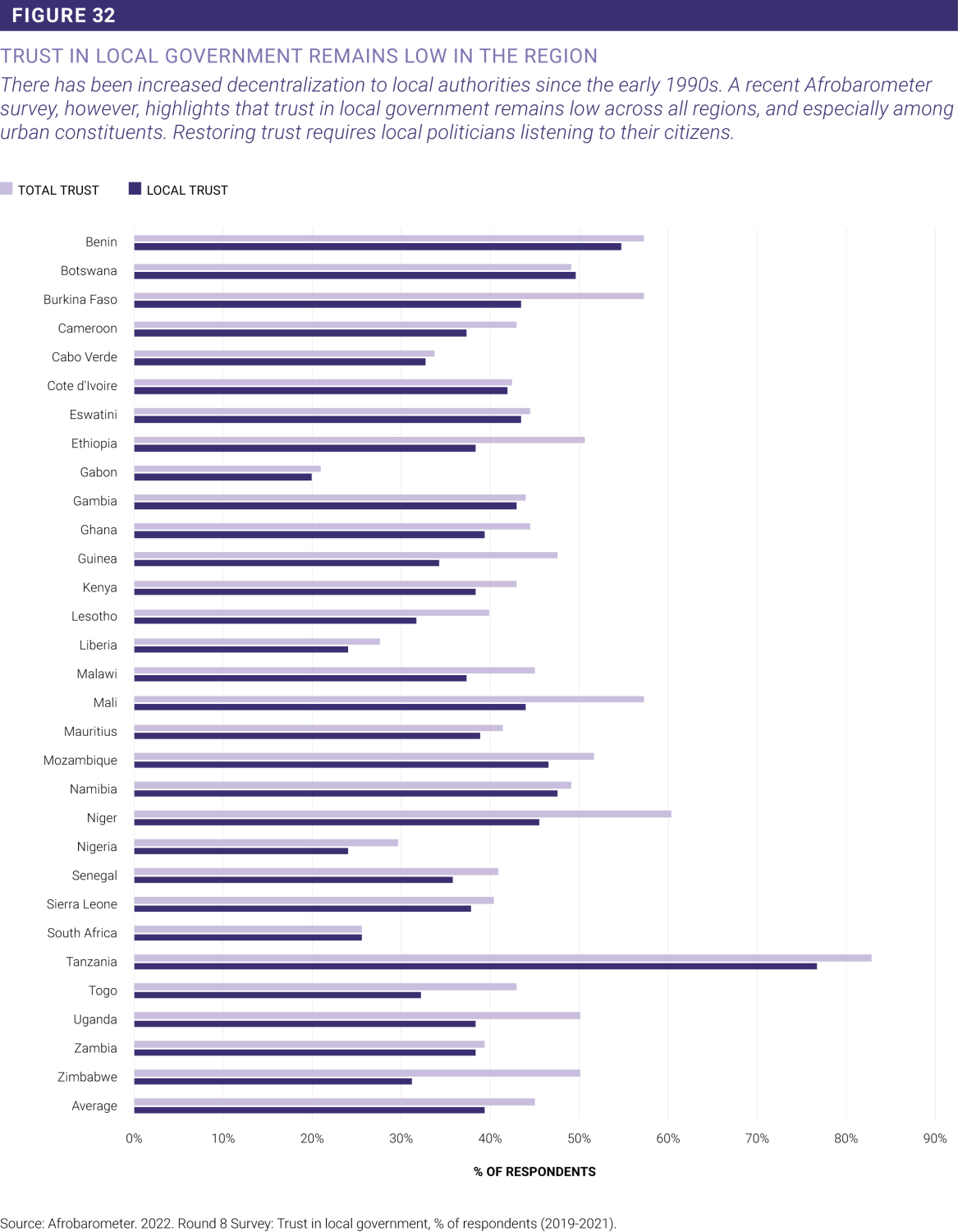

More broadly, data from Afrobarometer highlights that trust in local government remains, on average, quite low in the region (around 45%) and often lower in urban areas than in rural ones (see Figure 32). Given that local governments often have authority over policy issues most important to citizens, such as waste collection, primary health, education, and management of markets, this low trust may be partially driven by disappointment with service provision. Since engaging with local authorities over services often represents citizens’ most intensive encounter with participatory government, investments in local governance could be one potential route to improve public confidence in democratic systems more broadly in the region.

Investments in local governance and democracy

Such investments would involve prioritizing at least four areas. Enhancing the capacity and morale of local civil servants to perform their functions is one important domain. Indeed, one study of human resource capacity in 16 African cities and local governments revealed that local government administrations have management staff ratios of 1.4 per 1,000 inhabitants, compared with 36 per 1,000 inhabitants in developed countries.5 Salary payments for local civil servants may be months in arrears, and frequent transfers to new locations can also be problematic.6 A second priority is to improve the ability of local leaders to be truly representative of their constituencies. This would involve reducing onerous party registration fees to compete in local elections and using either legislated or voluntary quotas for women’s representation in local electoral contests.7 Third, several countries, such as Angola, and Liberia, need to finally implement their longstanding constitutional provisions to allow local elections. Thus far, such elections have been delayed because of either concern about giving the opposition a gateway to govern through local authorities or a lack of sufficient funding. Fourth and relatedly, the democracy and governance donor communities are well-placed to expand their focus from funding only presidential and parliamentary contests to also providing financial support for subnational elections. This might help reverse the relatively low levels of turnout that are typically seen for local elections, especially in countries where they are not concurrent with national ones.

In the coming years, local elections will be held in several countries across the continent. How those contests are managed, the ability of local authorities to provide much-needed services and accountability, and the capacity of local leaders to leverage transnational networks around critical development challenges will all be critical for reinforcing democratic principles and citizen trust from the bottom-up.

-

Footnotes

- Resnick, Danielle. 2021. “The Politics of Urban Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Regional & Federal Studies 31(1): 139–61.

- UCLG. 2023. Towards the Localization of the SDGs. Barcelona, Spain: United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG).

- SALGA. 2019. Violence in Local Government. Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Local Government Association (SALGA). Available at: https://www.salga.org.za/Batch%201%20-%20Latest%20Knowledge%20Products/ SALGA%20Study%20on%20Violence%20in%20Local%20Government.pdf.

- Mwareya, Ray. 2023. “South Africa: Councillors’ Political Murders at Crisis Level as 2024 Looms.” The Africa Report. Available at: https://www.theafricareport.com/327261/south-africa-councillors-political-murders-at-crisis-level-as-2024-looms/.

- Cities Alliance. 2017. Urban Governance and Services in Ghana Institutional, Financial and Functional Constraints to Effective Service Delivery. Brussels, Belgium: Cities Alliance. Available at: https://www.citiesalliance.org/sites/default/ files/Urban%20Governance%20and%20Services%20in%20Ghana.pdf.

- Resnick, Danielle, and Gilbert Siame. 2022. “Organizational Commitment in Local Government Bureaucracies: The Case of Zambia.” Governance, 36(3): 933-952.

- Berevoescu, Ionica, and Julie Ballington. 2021. Women’s Representation in Local Government: A Global Analysis. New York: UN Women.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Subnational democracy and local governance in Africa

February 8, 2024