Now that it is clear that geopolitical confrontation is part of the repertoire of U.S.-China relations, there is a danger that this bilateral relationship could divide the world, ushering in another bipolar competitive era.

But there are alternative dynamics that could pluralize U.S.-China relations by involving other actors, dynamics that could channel the relationship toward more international cooperation at a time when such cooperation is sorely needed. Within the G-20 grouping — which brings together the world’s major economies, which are also the major carbon emitters — there are opportunities for change. The G-20 could become a vehicle for more ambitious concerted global actions and a platform for addressing and managing geopolitical tensions.

Plurilateral dynamics

Throughout the 14 years that the G-20 has been meeting at leaders level, a handful of leaders have generated strong policy outcomes for the whole group. The composition of that relatively small group of leaders has varied from year to year. The G-20 is large enough to prompt shifts in these coalitions over time, as countries rotate in and out of the plurilateral leadership group.

This dynamic has increased the flexibility for officials to negotiate complex outcomes, avoiding rigid blocs that stifle innovation and reduce policy space. Plurilateral dynamics provide momentum and reward creativity, as well as generate buffers for managing U.S.-China geopolitical tensions as other significant countries assert their interests, presence, and influence.

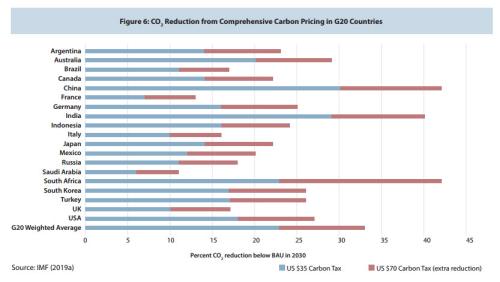

During this crucial transition year with the new U.S. administration, the most promising countries for leadership roles are Germany, France, Italy, Japan, Canada, Korea, the U.K., the United States, and China. Their leaders have the weight, the leadership, and technical skills to contribute to making the G-20 play crucial roles not only in addressing global challenges, but also in managing geopolitical relations. Not all of them will step forward. But that group is large enough to offer strong leadership to reform the G-20, as well as to drive global solutions to global problems — rather than lose momentum to systemic competition between the U.S. and China.

Recognizing China as a plausible member of the plurilateral leadership group could be an important breakthrough in easing geopolitical tensions.

Recognizing China as a plausible member of the plurilateral leadership group could be an important breakthrough in easing geopolitical tensions. China and the U.S. might actually agree on measures to strengthen G-20 and advance concerted action on public health, food security, climate change, the oceans, weather monitoring, and developing-country debt. There is every reason to believe that China could be a leading voice for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), because of its record in advancing the SDGs within China and the rest of the world since its G-20 presidency in 2016.

Strengthening the G-20

There are several ways that the G-20 could be strengthened in terms of institution-building and process reforms. (Many elements here flow from conversations I have had with the Right Honorable Paul Martin, who was finance minister of Canada for nine years in the 1990s before becoming prime minister. His efforts with American counterparts and others were crucial to developing the G-20 and mobilizing it to address global challenges.)

First, the most overarching innovation in how G-20 summits operate would be to intensify the preparatory meetings that lead up to the annual summits — making them month-to-month, week-to-week processes that produce results themselves, rather than focus largely on the peak moment of the two-day annual G-20 summit.

Too many of the existing series of G-20 meetings throughout the year are geared toward preparing for the once-a-year leader summits, instead of being vehicles for action themselves. No problem can be solved in one meeting. The current set of systemic threats and global challenges require greater and more regular engagement.

Accordingly, there needs to be less focus on G-20 summit communiqués by leaders and more focus on major problems and how to address them. Less focus on words, and more focus on actions.

Second, as a result, the G-20 can become a platform for ministers themselves to act, not only to feed ideas to their leaders and wait for them to act. G-20 countries, by definition, have sufficient weight in the world to drive change. In 2021, G-20 health and environment ministers could generate joint actions on global pandemic preparedness and on climate change as urgent issues. These precedents would encourage similar efforts by G-20 ministers in other realms, like employment, technology, biodiversity, education and training, and social cohesion in future years.

The G-20 group of finance ministers has proved to be an effective mechanism for collective action, but also has been able to create new institutions (like the Financial Stability Board) and benefit from institutions (like the International Monetary Fund and the OECD), which support, pressure, and serve the G-20.

Third, ministers with other portfolios could follow this model and create new institutions that support, implement, and encourage their actions and use existing institutions to amplify their work. There are notable weaknesses in international institutions in the realms of global health and global warming. The World Health Organization is neither an action platform nor does it have credible financing. G-20 health ministers acting together could change this. The U.N. Environment Programme has a broad environmental agenda; what is lacking is a more prestigious and powerful international institution focused solely on climate change threats and accelerating the pace of national climate change actions. G-20 environment ministers could lead an effort to create a climate stabilizing agency to vigorously monitor and enforce climate change commitments.

Include security issues

To leave geopolitical issues off the G-20 agenda is to ignore the elephants in the room. The most important change would be to enable the G-20 to address geopolitical tensions directly by opening summit agendas to selective strategic and political security issues and to include foreign and defense ministers and officials in some G-20 processes.

To leave geopolitical issues off the G-20 agenda is to ignore the elephants in the room.

Brookings colleague Bruce Jones first recommended including security issues in G-20 summits at the entity’s creation. There have been occasional foreign minister meetings, but they have been episodic and only partially attended. Security issues have sometimes come up at summit dinners, for example, but they have never been part of the G-20 work program. Freedom of navigation, cyberwarfare governance guidelines, and human rights (in Myanmar, for instance) are examples of the kinds of security issues that could be usefully discussed in the G-20 setting, because most nations have a stake in these issues.

The proposal here is to open the agenda to security issues so that G-20 leaders and senior officials could decide what to bring up (and when) to encourage propitious discussions. Given heightened geopolitical tensions today, security issues have become the backstory of global governance. Opening the G-20 agenda to security issues could be the single most important step to strengthen global governance in the 2020s, since these issues are dominating the global order now, and need to be managed collectively.

Connecting with people

These steps can help the G-20 broaden and deepen its agenda, creating continuing processes throughout the year that focus public and parliamentary attention on concerted actions by major countries that have consequences for people. Too much of G-20 activity is insider baseball among banks, corporations, and bureaucrats, and not about political leadership on behalf of the public interest. There is more time spent on how to send the right signals to markets, interest groups, and officials than on communicating with publics and legislators. The excitement of international cooperation and understanding across cultures, professions, and sectors is lost in a welter of technical jargon and official wordsmithing, with economics and financial jargon drowning out layman’s language. As a result, G-20 summits have seemed remote and unrelated to real life of ordinary people. Leaders have lost connections to their societies at these events, instead of bringing their publics into them by resonating with and responding to their concerns.

Senior political advisers to G-20 heads of state and government need to involve themselves in summits and G-20 sherpas need to exert greater influence to reconnect their leaders to their publics by managing the G-20 communications processes to prioritize content that is relevant and meaningful to citizens and social issues.

Finally, there is a problem of consistency and follow-through from year to year, as the country hosting the G-20 summit changes annually. Continuity could be markedly improved by creating a small but effective secretariat to see issues through from incubation, to consultation, to teeing up for leaders, to decisions, to communications, to implementation, to monitoring and evaluation. The secretariat should also be charged with making the G-20 processes throughout the year more effective in ensuring that commitments are fulfilled and plans are implemented consistently year after year.

Conclusion

Given the current state of U.S.-China relations, many think the global order faces another bipolar competitive era. Actively energizing plurilateral leadership and diplomacy, involving other countries in altering the geopolitical dynamics, could be a game changer. There is no reason to leave China and the US alone to work out their bilateral relationship in which all countries have immense stakes.

The G-20 is a promising forum for addressing the geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China. Taking actions to strengthen the G-20 and engage these tensions within the G20, rather than avoid them, could be the most promising steps to empower global governance to meet the global challenges of the 2020s. The G-20 could become the forum within which U.S.-China relations could be most successfully improved, by relying on the presence of other countries to pressure both states to exercise global leadership on behalf of the whole world, instead of competing to divide it. Plurilateral leadership that includes China and the US embedded in the G-20 is a powerful opportunity to move the global agenda forward and multilateralize the management of geopolitical tensions at the same time.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Strengthening the G-20 in an era of great power geopolitical competition

April 27, 2021