There are two ways of looking at the outcome of the European Parliament elections in Germany. On the European level, the fact that Germany’s conservative opposition (the Christian Democratic Union, CDU) came in first helped the European People’s Party (EPP), the transnational grouping of Europe’s mainstream center-right parties, to gain seats. That makes the EPP likely to form the core of the coalition that will elect the European Union’s leadership for the next five years, probably reappointing EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who comes from the CDU herself. Despite the far right’s electoral gains across much of Europe, the EPP’s hold on power will provide some much-needed continuity and stability at a time of global uncertainty and strategic risks for Europe.

But inasmuch as the European Parliament elections are managed by the EU’s member states and contested by national political parties, they are always also a referendum on the incumbent national government. Here the picture is more fraught. And this, in turn, can have consequences for Germany’s ability to pull its weight in Europe.

The election shows a Germany divided—politically and geographically

According to the preliminary final count of the German votes, the CDU and CSU together got 30% of the vote (a 1.1% increase from the last election in 2019). The hard-right AfD received 15.9% (up by 4.9%), putting it in second place nationwide (and in first place throughout the five eastern German states).

The parties of the ruling traffic light coalition, meanwhile, were given a trouncing: Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats got 13.9% (down by 1.9%), their worst result ever in a European election; the Greens came in at 11.9% (down by a stunning 8.6%), and the Liberals at 5.2% (down by 0.2%).

The Left Party continues its downward trajectory at 2.7% (down by 2.8%), while its renegade offshoot, the hard-left BSW party founded only in January by the fiery populist Sahra Wagenknecht, achieved 6.2%. Voter turnout in Germany was at 64.8%, the highest since 1990 and more than 10 percentage points above the EU average. Clearly, voters were galvanized and wanted to send a message.

The drubbing for Scholz’s team in Berlin came as no surprise, given consistent poll predictions and the coalition’s very public infighting in recent months. But for a government hoping to recover some mojo before three bellwether eastern state elections in September and national elections a year later, it is nonetheless demoralizing. Scholz’s “I-am-the-chancellor-of-peace-and-prudence” message left voters deeply unpersuaded. The Greens alienated Germans with a combination of maximalist climate policies, amateurish governance blunders, and naïve nepotism; the Liberals’ rigid hawkishness on defense and fiscal probity obviously isn’t working for them either.

Snap elections are rare, so the government will struggle on

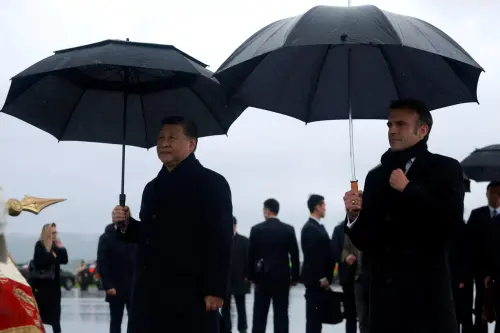

Unlike in France, however—where President Emmanuel Macron immediately dissolved the parliament and announced new elections to be held on June 30 and July 7 after his party’s devastating defeat by far-right leader Marine Le Pen and her National Rally party (see my colleague Tara Varma’s analysis), early elections are highly unlikely in Germany. The German constitutional court has made it abundantly clear that it frowns on a chancellor calling a confidence vote in order to wrongfoot his opponent with an early election. And there are no signs that the CDU with its leader Friedrich Merz has the political capital (or the necessary coalition partners) to win a parliamentary vote of no confidence against Scholz; especially since it hasn’t even formally decided yet that Merz will be its candidate in 2025. Demands by the opposition leaders for Scholz to follow Macron’s example are just political kabuki.

Germany’s traffic light coalition will therefore struggle on unhappily—and the CDU has every reason to temper its swagger with self-awareness. The net result, alas, may be a German political center that becomes more nervous and more inward-looking at precisely the time when Europe could use energetic leadership from Berlin.

Extremists on the left and right are the election’s real winners

So, at the national level, the real winners of this election are arguably the AfD and the BSW. They have real differences: Segments of the AfD have been designated as right-wing extremists by Germany’s domestic intelligence agencies, whereas the BSW, while distinctly populist, has not come under similar scrutiny. Many of the BSW’s voters are defectors from the mainstream left and skew toward older age groups; the AfD’s vote share was especially strong among young and first-time voters.

But they also have some big things in common. Both are skeptical of the European Union and have a distinct nationalist bent. They play on voters’ fears about migration, the economy, and security; they sharpen polarization by decrying their centrist opponents as out-of-touch elites; they share a notable warmth toward Russia and China.

Finally, look at a map of which party came in first in the weekend’s European Parliament election in Germany, and it looks shockingly like a map from 34 years ago. The territory of the former West Germany is almost uniformly black (the color of the conservative CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union or CSU), while the territory of the former East Germany—part of the Soviet-dominated Warsaw Pact until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989—is blue (the color of the hard-right Alternative for Germany, AfD) except for the country’s capital, Berlin. It is as though the reunification of Germany in 1990 had never happened.

In fact, both the AfD and the BSW have their greatest followings in the former East Germany. There has been much debate about why this is the case—and there is conflicting evidence about whether their voters cast their ballots in protest or out of conviction. Also, party identification is weaker in Germany’s east than in other parts of the country. But clearly, 34 years of reunification have not sufficed to erase the wounds of 44 years of Communist rule and the tremendous costs of transformation after the fall of the wall. The populists and extremists are exquisitely skilled at exploiting these divides. That is a lesson the mainstream parties would do well to heed.

The fact remains that the largest gains of the weekend’s vote in Germany were made by the AfD, which is Europe’s most overtly radical far-right party. Earlier in the year, it unleashed week-long protest marches across the country after revelations of a secret meeting between AfD members and other figures of the extreme right to discuss the “remigration”—deportation—of immigrants, including German citizens with an immigrant background. One of its legislators was stripped of his immunity because of links to Russian oligarchs peddling disinformation. Its top candidate for the European election, Maximilian Krah, saw one of his staffers arrested on suspicion of espionage for China and was later sidelined (but not removed as a candidate) by his own party for saying that not all members of the SS had been criminals.

The AfD uses and abuses history

It so happens I am writing this blog from southern Germany, near Munich. The day after the election, I went to see the Dachau concentration camp—built in 1933 for political prisoners, and now a historical memorial. Between 1933 and 1945, 200,000 people were incarcerated there, abused, tortured, and finally, as the Allies advanced, sent on death marches; at least 41,000 were killed. The camp was run by the SS, and it was where the Nazi regime’s most-feared paramilitary group developed the methods it later perfected in extermination camps across Germany and Eastern Europe, killing millions.

The AfD delegation in the European Parliament has expelled Krah from its group—but many other key figures have repeatedly made a point of minimizing Germany’s guilt in the Holocaust. And Krah remains a sitting member of the European Parliament from Germany. That is still shocking. Thankfully, memorials like Dachau continue to display and teach the historic truth to visitors; and there were many on the day I went.

Commentary

Stability for Europe, tensions at home: Germany’s paradoxical European Parliament vote

June 11, 2024