Editor’s Note: With Paul Ryan’s rise to become Speaker of the House, he faces a set of immediate challenges that will help determine his legacy. Over the coming weeks, Molly Reynolds will profile some of the major issues and legislation Speaker Ryan will be forced to address.The first post in the series addressed Ryan’s ability to keep his promises to the rank and file. She will also assess both his performance on those matters and the consequences of the choices both he and the House of Representatives make.

This week, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan (R-WI) followed through on a second promise to open up the legislative process. The House Republican Conference approved a set of reforms to the party’s Steering Committee—the panel responsible for assigning members to policy-oriented standing committees (e.g. Armed Services, Ways and Means) and selecting those panels’ chairs. In this role, the committee can be a tool for maintaining party discipline, such as in December 2012, when four Republicans were removed from their posts on the Budget and Financial Services committees for voting against the Republican leadership’s party line. While the Steering Committee is most active right after an election, it is occasionally called to make new choices mid-session, such as its recent elevation of Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX) to replace Speaker Ryan as the chair of the Ways and Means Committee.

When Ryan assumed the Speakership, the Steering Committee had 33 members. Some, like the Speaker and the Majority Leader, served by virtue of other roles they hold. Thirteen other members served as regional representatives, selected by subgroups of legislators from a particular area. In addition, there were four “junior class” members, representing the interests of legislators elected for the first time in each of the last three elections. All members had a single vote, except for the Speaker, who had five and the Majority Leader, who had two.

Under the proposal approved this week, however, six of the committee’s ex-officio members—the chairs of the Appropriations; Energy and Commerce; Financial Services; Rules; Ways and Means; and Budget committees—will lose their Steering Committee seats. They’ll be replaced by six new, non-ex-officio members. For the duration of the current Congress, these new members will be selected by a vote of the full House Republican Conference. When the 115th Congress convenes in January 2017, those six seats will become additional regional seats, bringing that total to 19. Finally, the number of votes explicitly controlled by the Speaker will be reduced from five to four, but the Speaker will gain the ability to appoint an at-large member to “address gaps in representation.”

These reforms will restructure roughly one-fifth of the panel’s representation—but how much difference will they make? First and foremost, the symbolism of removing six committee chairs with a combined 66 years of experience in Congress in favor of members selected by their peers is important as Ryan tries to follow through on his pledge to open up the process to more influence from rank-and-file members. The shift to six at-large seats for the remainder of this Congress will also likely infuse some new and interesting blood into the panel in the short term. Any Republican member will be able to run for one of these slots. Each representative will have one vote to cast, with the top six vote-getters receiving seats. This voting rule (known in the language of political science as a single non-transferable vote system) means that if a candidate gets just more than 14% of the vote—or roughly 36 votes in the current House Republican Conference—he or she is guaranteed a seat. Current estimates of the House Freedom Caucus roster put the group’s size between 36 and 39, so it would likely not be hard for the group to get at least one member on the Steering Committee if they wanted to.

While the Freedom Caucus may well benefit from the new at-large seats, the reforms don’t go as far at opening up the panel as some conservative Republicans had advocated. An alternative plan for reforming the Steering Committee would have reduced the Republican leadership’s influence on the panel even further, removing four other members who serve as a result of holding other leadership positions. Under that proposal, the Speaker and Majority Leader would have also only controlled a single vote.

Not only does the reform proposal fall short of decentralizing power as much as some conservatives wanted, it also pales in comparison to the influence of non-leadership members on the Steering Committee’s predecessor, the Republican Committee on Committees (RCC). Prior to Newt Gingrich’s restructuring of the committee assignment process following the 1994 elections, votes were assigned largely on the basis of the size of a state’s Republican delegation in the chamber. During the 103rd Congress (1993-94), for example, California controlled roughly 11 percent of the votes on the RCC (22 of 196 total votes), while Florida controlled approximately 7.5 percent (15 votes).1 Between the Minority Leader’s 12 votes and the Whip’s 6, the Republican leadership controlled roughly 9 percent of the votes. By comparison, even after this most recent round of reforms, Ryan alone will still control roughly 10 percent of the votes on the Steering Committee (4 of 39); his influence will still loom large.

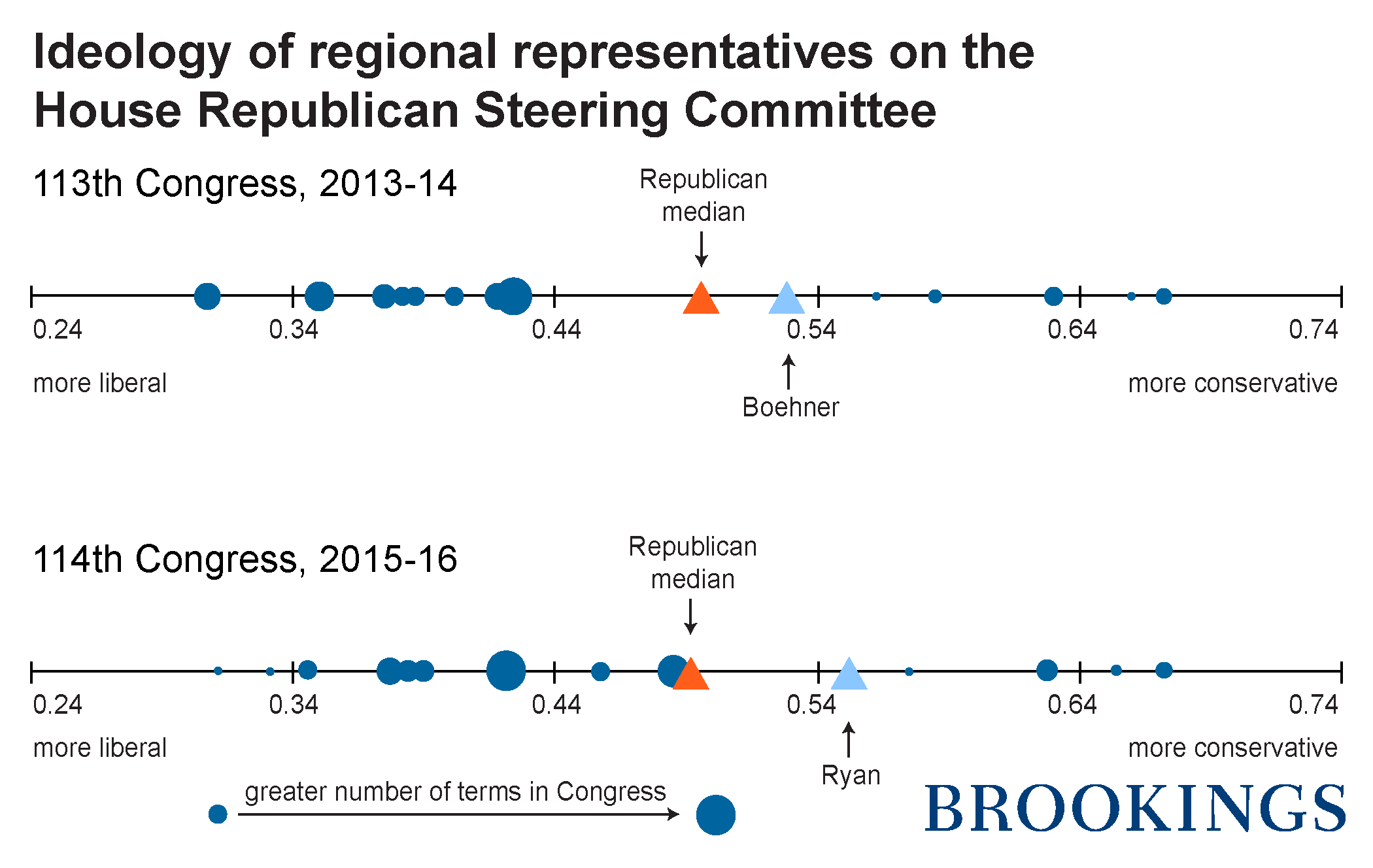

Given the increasing centralization of power in the House since 1994, returning a regime fully dominated by geography would likely be a tough sell. But will electing more regional members change the panel significantly? To capture current dynamics in regional member selection, the figure below displays the regional members from the previous (113th) and current (114th) Congresses. Each circle represents a Steering Committee member, with larger circles indicating more senior legislators. More moderate Republicans are on the left and more conservative members are on the right, with ideology measured using Common Space DW-NOMINATE scores. (The Speaker of the House and the median Republican member are included as triangles for reference.) As we can see, the recent sets of geographically-elected members span the full range of the Republican caucus, both ideologically and in terms of seniority. Unless the selection rule (secret ballot) for regional seats also changes, there’s a distinct possibility that the 115th Congress will see a similar, relatively diverse set of regional representatives.

Source material:

List of regional representatives in the 113th Congress

;

List of regional representatives in the 114th Congress

Certainly, some of the new regional members will likely be from the more conservative wing of the caucus. Indeed, one state likely to benefit from the additional geographic representation is Arizona, which has a relatively conservative delegation (average Common Space DW-NOMINATE score of 0.584) and has been disadvantaged of late by its placement in the same region as California, whose members outnumber Arizona’s 14 to 5. As political scientist Eric Schickler has documented, moreover, junior members seeking power and a dissident faction within the majority party have previously cooperated to produce meaningful decentralization in the House’s power structure. Will this round of Steering Committee reforms do the same? Only time will tell.

1. Mary Jacoby, “Big States Losers in Gingrich’s Plan for Committee on Committees,” Roll Call 1 December 1994.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Speaker Ryan is “steering” the Congress toward more changes

November 20, 2015