While national and statewide polling will continue at a furious pace as we head into the presidential election year, it is important to look at the actual votes in recent elections to gain a sense of which way the political winds are blowing. From this perspective, both Tuesday’s off-year election and the 2018 midterms indicate that Democrats are in a favorable position in their 2020 quest for the White House.

Tuesday’s election highlights

The marquee elections earlier this week were in Kentucky and Virginia. In Kentucky, Democrat Andy Beshear received 5,000 more votes than his Republican rival, incumbent governor Matt Bevin, in a state that Donald Trump won by nearly 600,000 votes in 2016. With high turnout for an off-year election, Beshear’s largest vote gains came from urban Louisville and Lexington as well as from suburban counties including Kenton and Campbell, which are just across the state line from Cincinnati.

Democratic candidates were defeated in the Bluegrass state’s down-ballot contests. But the fact that they succeeded in the gubernatorial race in this deep red territory is noteworthy, especially in light of the fact that Bevin tied his campaign to support for President Trump, who led a rally for the governor the day before the election.

Election Day in Virginia brought about the commonwealth’s first Democratic majority in both its House of Delegates and Senate which, along with the Democratic governor, provides the party with its first full control of government since 1994. Democrats gained six new delegates and two new senators, spurred by high turnout and support in the suburbs of northern Virginia (outside Washington, D.C.) and urban and suburban areas around Richmond and Hampton Roads. Over the past decade, these suburbs have become more racially diverse and highly educated—attributes that favor Democrats, particularly since President Trump became the Republican Party standard-bearer.

Democrats lost the other big race this week—the governorship of Mississippi—though Republican candidate Tate Reeves won by one of the smallest margins (6%) in recent state history over Democrat Jim Hood. Overall, in Kentucky, Virginia, as well as in the Philadelphia region, the higher turnout and strong suburban vote suggest that Democrats have continued their momentum since last year’s midterms.

A look back at the 2018 midterm elections

This week’s results show that voting trends revealed in last November’s midterms are holding steady. Donald Trump was not on the ballot in 2018, but in many ways the midterm results can be interpreted as a referendum on him. The tallied votes revealed significant changes in state and county voting patterns, demographic preferences, and voter turnout.

Democratic voting margins increased in states key to the 2020 election

The Democratic takeover of the U.S. House of Representatives was the key result from 2018’s midterms. But another way to examine the party’s gains is to compare House votes statewide with those from the 2016 presidential election. Map 1 depicts each state’s Democratic or Republican vote advantages based on 2018 House votes:

It differs from the results of the 2016 presidential map, where Trump won based on support from states such as Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Arizona. As Map 1 reveals, each of these states registered Democratic advantages in the 2018 House elections. If those results hold for 2020, the Democratic candidate could receive 296 Electoral College votes—enough to win the presidency.

In all but two states, House Democrat minus Republican (D-R) voting margins (percent voting Democrat minus percent voting Republican) showed more positive or less negative values than those for the 2016 presidential race—both in “red” states and in “blue” ones (download Table A). In Virginia, for example, the 2016 presidential D-R margin of 5.7 increased to 14 in the 2018 House election results. In Texas, the 2016 D-R margin of -9.4 decreased to just -3.5 in 2018.

More than four-fifths of 2018 voters resided in counties with rising Democratic support

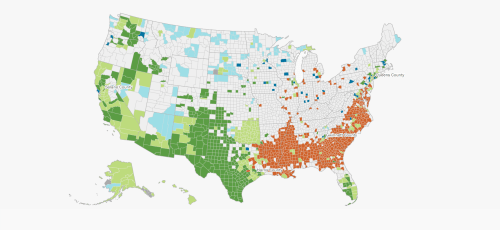

Of course, 2018 Democratic and Republican vote advantages differ across counties. House votes for Republicans exceeded those for Democrats in more counties nationwide—many of them smaller-sized counties in exurban, small metropolitan, and rural areas. However, in a vast majority of counties—even those which Republicans won in 2018—more voters favored Democrats in 2018 than in 2016. This can be seen in Map 2, which depicts changes in D-R margins between the 2016 and 2018. In 2,445 out of 3,111 counties, regardless of whether the final midterm vote favored the Republican or Democratic candidate, there was a positive D-R margin shift between 2016 and 2018—meaning either a greater Democratic advantage or a smaller Republican one.

At one extreme are counties in New England states—Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island—which voted Democratic in 2018. Most of those counties also showed strong 2016-2018 gains in their D-R margins (shown in Map 2). At the other extreme are counties in states such as Kentucky, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, which voted heavily Republican in 2018. Even so, as Map 2 indicates, most of those counties showed a greater D-R margin (meaning reduced Republican support overall) between 2016 and 2018.

In 2018, 83% of voters resided in counties that increased their D-R margins since 2016, including 26% that increased their D-R margins by more than 10, and 57% that increased their margins by 0 to 9. Increased D-R margins were prominent among voters in counties that voted both Democratic and Republican in 2018.

Counties with sharply increased D-R margins tend to have “Republican-leaning” attributes, when compared with all counties: greater shares of noncollege whites and persons over age 45, and smaller shares of minorities and foreign-born persons. This occurs among both Democratic-voting and Republican-voting counties, suggesting there was a shift toward Democratic support for groups in counties that helped to elect Donald Trump in 2016.

Increased 2018 Democratic support occurred in the suburbs

Democrats have long done well in large urban core counties, while Republicans tended to be more popular in suburbs, small metropolitan areas, and rural communities. Figure 1 shows that this characterization weakened in 2018 House elections, presaging the suburban Democratic gains observed this week.

In both 2016 and 2018, urban core counties in large metropolitan areas exhibited strong positive D-R margins, while small metropolitan and outside-metropolitan-area counties showed negative (Republican-favorable) D-R margins. Yet in suburban counties in large metropolitan areas, there was a shift between the 2016 and 2018 elections from a negative to a positive D-R margin. Also, the D-R margin became more positive in large urban cores and less negative for counties outside large cores and suburbs.

As with the nation as a whole, most voters in each category resided in counties where D-R margins became more positive or less negative between the 2016 and 2018 elections. This is especially notable for large suburbs, where 87% of voters resided in counties with increased D-R margins.

The 2018 midterms showed greater Democratic support among white voters

Racial differences continue to represent a primary fault line in voting preferences, with whites overall favoring Republicans, and minorities—especially Black voters—favoring Democrats. When comparing the national vote for the 2018 House of Representatives with the 2016 presidential vote, the white Republican vote advantage diminished by half, from a D-R of -20 in 2016 to -10 in 2018. In contrast, the positive D-R margins favoring Democrats remained the same or increased for Black voters, Latino or Hispanic voters, and voters of other races.

Perhaps even more important for the 2020 election results will be the gender and education divides in white voting. As political analyst Ronald Brownstein has noted, white, college-educated women are a likely long-term Democratic-leaning voting bloc, in contrast to other white groups, especially white men without college educations. It was the latter group, in particular, that has been credited with providing strong support for Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

In contrast to that election, the 2018 exit polls show markedly reduced Republican support from white, non-college-educated men, and increased Democratic support from white, college-educated women, with their D-R voting margin rising to +20, up from +7 in 2016. The diminished support for Republicans among white men without college educations was especially apparent in 2018 senatorial and gubernatorial elections in the critical states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

The 2018 midterm turnout surge favored Democratic-leaning groups

Again, paralleling this week’s elections, the turnout for the 2018 midterms was extraordinary. Census Bureau estimates show that 2018 turnout—53.4%—was the highest in midterm elections since it started collecting voter turnout numbers in 1978, and the first time since 1982 that it rose above 50%. A careful look at the data shows groups that voted Democrat last year also displayed some of the biggest increases in voter turnout. Young adults aged 18 to 29—the age group that voted most strongly Democratic—saw a rise in their turnout rate from 20% in 2014 to 36% in 2018. Of course, older voters aged 65 and above continued to display the highest turnout levels (66%), but the increase among young adults in 2018 served to narrow the young-old turnout gap.

All major race-ethnic groups had higher turnout in 2018, but the biggest gains accrued to Democrat-leaning Latino or Hispanic and Asian American voters—up 13% since 2014. And while whites overall exhibited higher turnout than other groups, both the turnout level and recent rise were highest for white college graduates—the white group with the highest Democratic preference.

Focusing further on young adults, census turnout data reveal that 18- to 29-year-olds of each major race group showed substantially higher turnout in 2018 than four years prior, more than doubling for young Latino or Hispanic and Asian American voters and nearly doubling for young whites. The latter is especially noteworthy because, unlike in the 2016 presidential race, young whites voted Democratic in last November’s House elections, joining their age group counterparts of other races.

Recent voting trends favor Democrats

Clearly, this week’s results for Kentucky governor and Virginia statehouse seats are positive signs for Democrats, especially when viewed on top of the heft and breadth of Democratic-leaning voting trends from the 2018 midterms. The latter strongly suggest movement toward increased Democratic or reduced Republican margins for large swaths of the country, across regions and especially in the suburbs. There appears to be reduced Republican support among white voters without college degrees—especially males—along with increased Democratic support among white, college-educated women. Moreover, both the 2018 midterms and this week’s off-year elections underscore the fact that turnout in 2020 is likely to be higher than in recent elections, rising especially among Democratic-leaning groups such as the young, minorities, and highly educated.

Of course, a lot can happen in the next year, especially with a still-undecided Democratic candidate and the potential impeachment and trial of President Trump. However, several underlying forces revealed in the 2018 and 2019 November elections suggest a swing toward Democrats is possible—assuming they are able to capitalize on it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).