Below is the essay from Chapter 6 of the Foresight Africa 2018 report, which explores six overarching themes that provide opportunities for Africa to overcome its obstacles and spur inclusive growth. Download the paper to see the contributing viewpoints from high-level policymakers and other Africa experts. You can also join the conversation using #ForesightAfrica. Pour lire ce chapitre en Français, cliquez ici.

china and africa: crouching lion, retreating dragon?

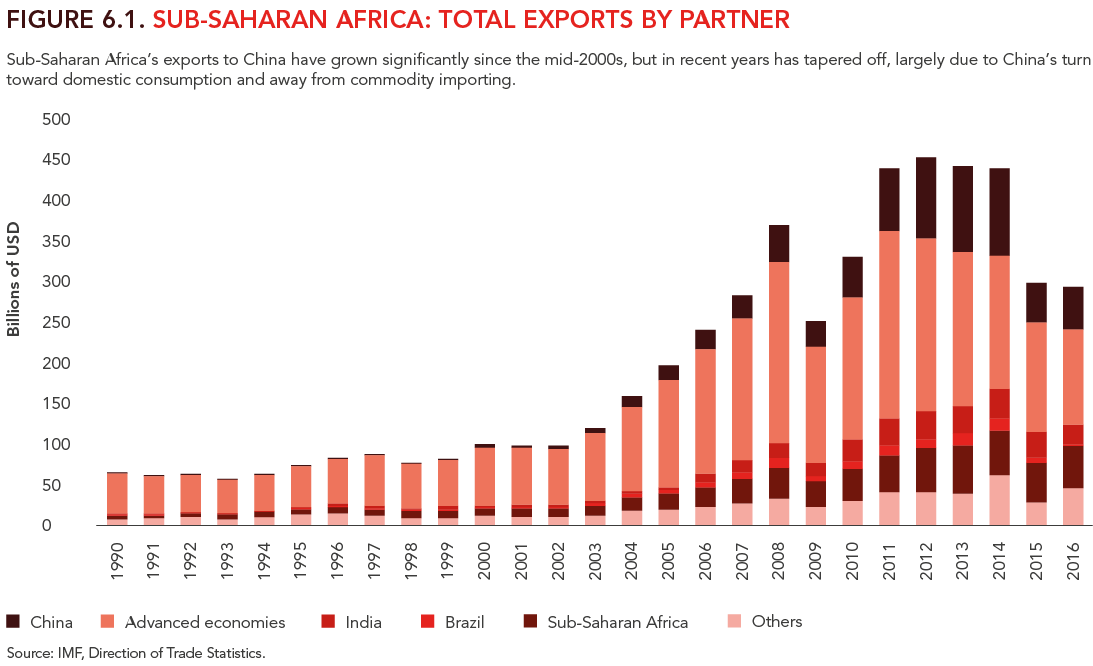

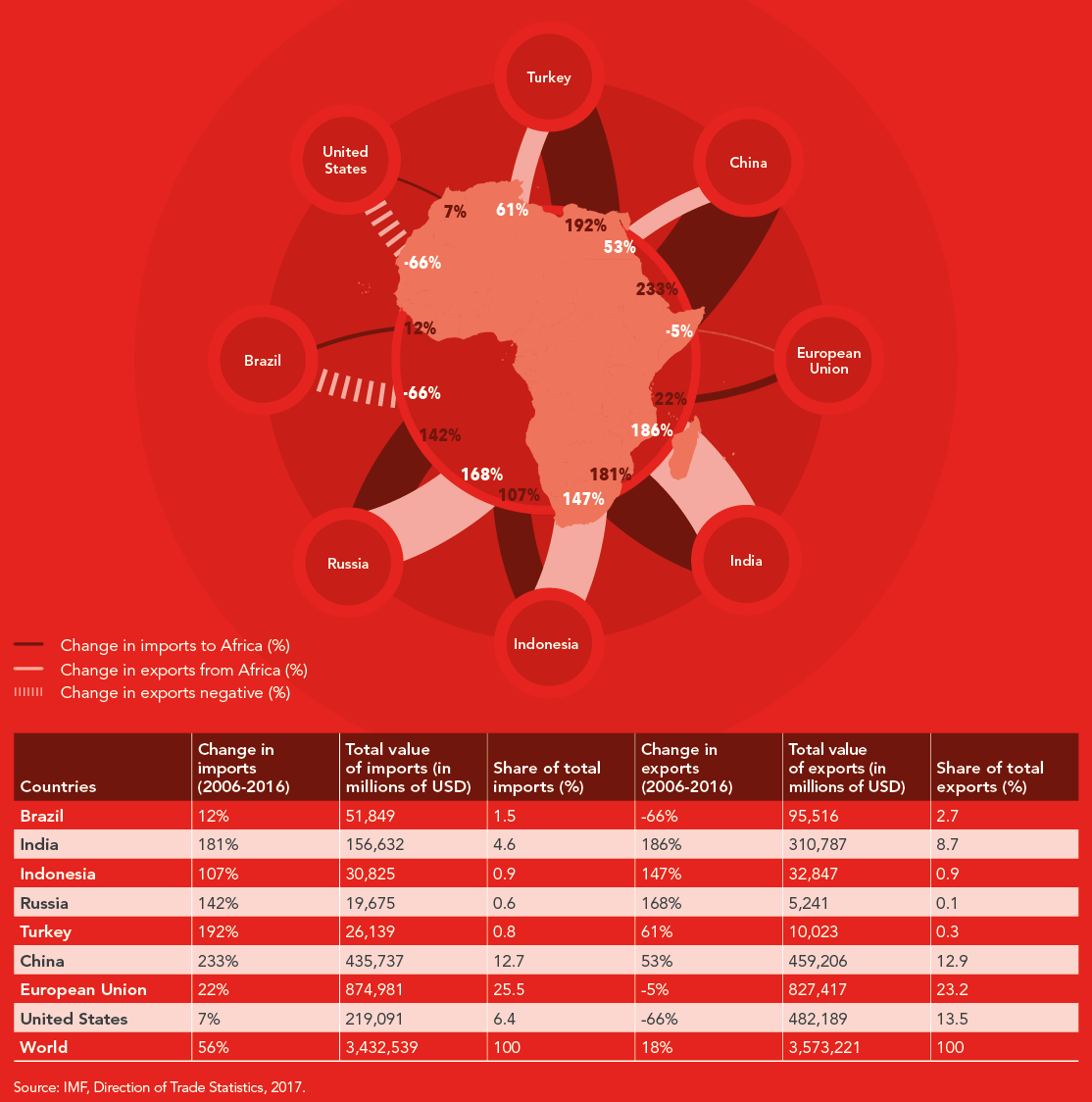

Africa has forged close economic ties with China over the past 20 years. There are two main channels of economic engagement between Africa and China. The main channel, by far, has been through trade, having risen more than 40-fold over the period. Most sub-Saharan African exports to China are fuels, metals, or mineral products. On the other hand, imports from China to sub-Saharan African countries comprise mostly manufactured goods, followed by machinery.

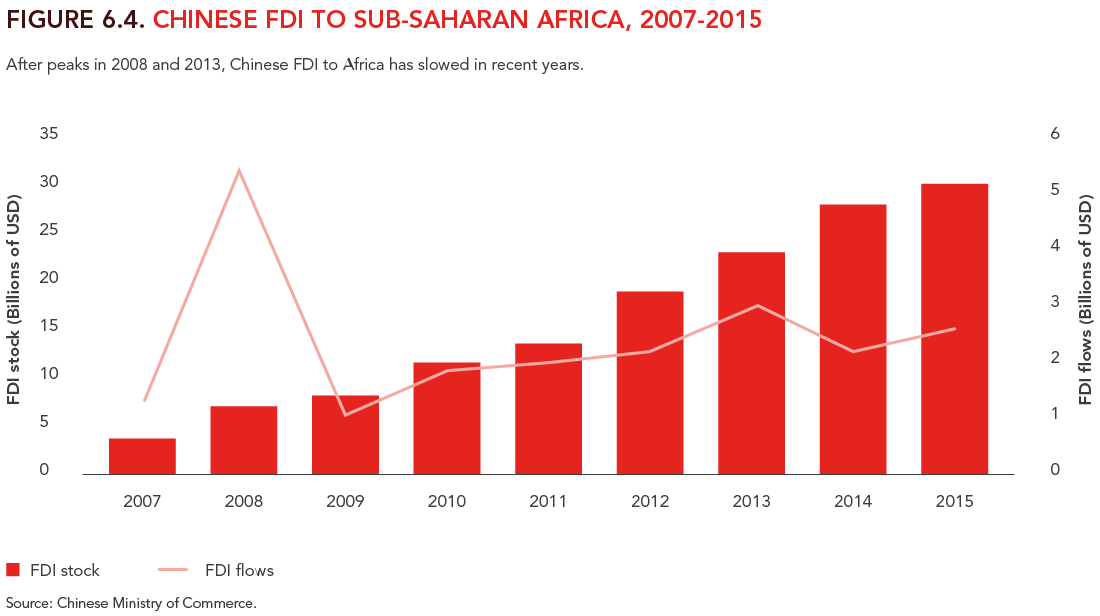

The second main channel of engagement between Africa and China is through Chinese lending. China has become, by far, the largest source of bilateral loans, accounting for about 14 percent of stock of total debt contracted by sub-Saharan African countries, excluding South Africa. Contrary to popular perception, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa remains small—accounting for only a little over 5 percent of the total FDI flow in 2015.

This rapid growth in trade and project financing has served both Africa and China well. For Africa, trade has boosted economic development in many countries, and the financing of infrastructure projects, for which little concessional financing is available, has helped address crucial bottlenecks to industrial development and structural transformation. For China, while trade with Africa remains a small part of its total foreign trade, many of its project loans are tied to Chinese suppliers, and, as a result, about a quarter of all Chinese engineering contracts worldwide by 2013 on a stock basis went to sub-Saharan Africa, with most of these contracts being awarded in energy (hydropower) and transport (roads, railways, ports, or aviation).

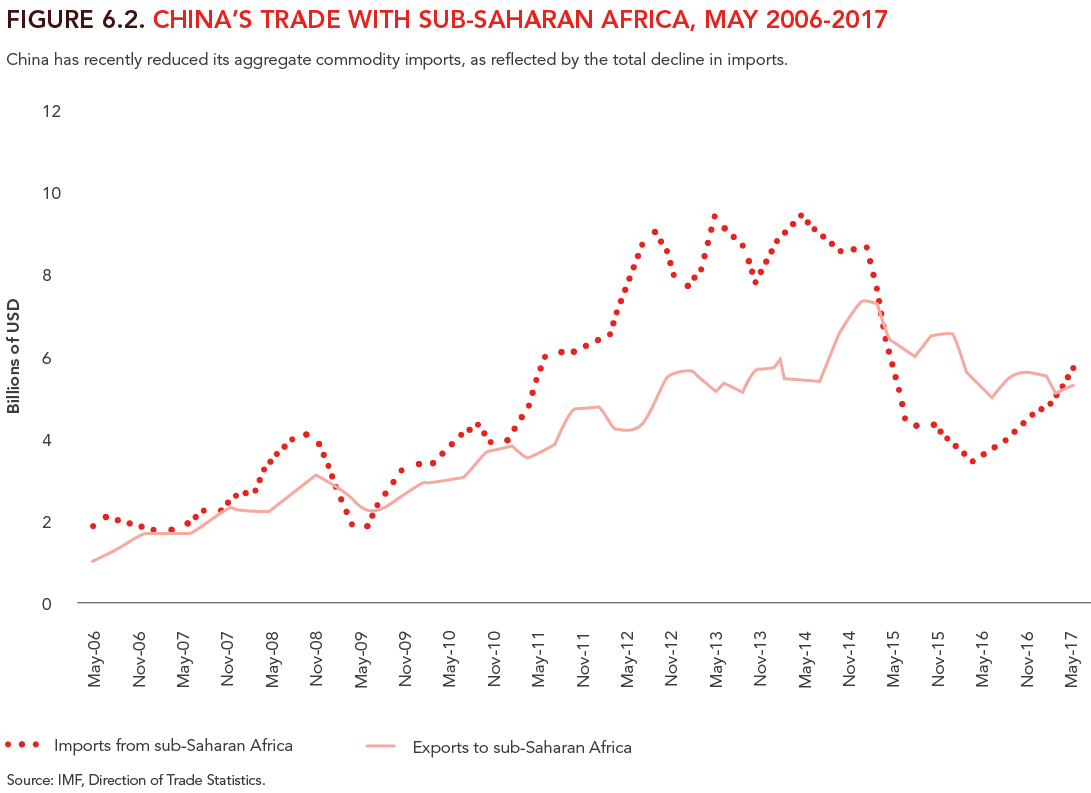

Africa’s almost decade-old trade surplus with China has now turned into a trade deficit as lower growth in Africa curbs import demand.

Nevertheless, these synergies are coming under severe strain. On the trade side, China’s growth is rebalancing away from investment toward relying increasingly on domestic consumption. The resulting drop in China’s imports of commodities has hit Africa’s commodity exporters hard, especially the oil producers, through sharp declines in both the volume and prices of major commodities (Chen and Nord, 2017). Africa’s almost decade-old trade surplus with China has now turned into a trade deficit as lower growth in Africa curbs import demand (IMF, 2017).

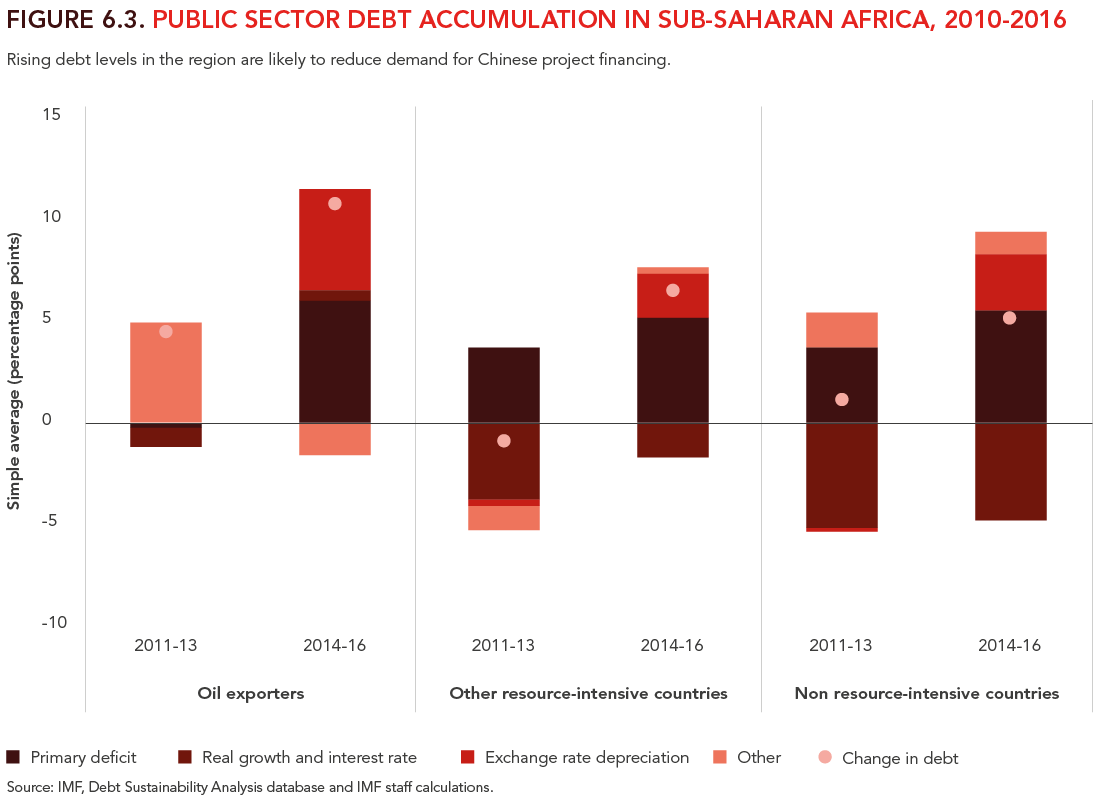

Additionally, borrowing space in African countries is shrinking rapidly. Despite the availability of financing, such as under China’s One Belt One Road Initiative, the sharp slowdown in growth in commodity exporters is reducing the demand and the feasibility of large infrastructure projects in those countries. Some are already facing difficulty servicing existing loans. Moreover, while growth is holding up in many non-commodity exporters, rising debt levels are likely to curb Chinese appetite for future project financing. Indeed, public debt in the median sub-Saharan African country rose from 34 percent of GDP in 2013 to an estimated 53 percent in 2017, and debt service as a share of revenue has doubled. In some oil-producing countries such as Angola, Gabon, and Nigeria, debt service amounts to more than 60 percent of government revenues. So, with trade and project financing under pressure, can FDI pick up the slack?

Based on official data from China’s Ministry of Commerce, FDI flows from China to Africa peaked in 2008 and 2013 and have slowed down markedly since then. Notably, this decline in Chinese FDI to Africa is occurring despite a surge in Chinese outward capital flow, especially by Chinese corporations, signaling investors’ continued appetite for investments and high returns outside China. Of course, this trend is only indicative of the short term.

In the longer term, whether and how much Chinese FDI flows to Africa will depend on how African countries, especially those reliant on commodities, weather this period of low growth and fiscal pressures. The non-commodity-dependent frontier economies in East Africa, for example, could be very attractive new growth markets in the medium term. In fact, this area might be particularly attractive to Chinese FDI that extends well beyond the natural resource sector (Chen, Dollar, and Tang, 2016). As China continues to move up to higher-value-added supply chains, wages move up, and its population ages, sub-Saharan Africa has a unique chance to step into this space. However, the structural transformation needed to achieve that will require investment, notably in infrastructure, just as official borrowing space is shrinking. That will put a premium on careful project selection to ensure maximum impact. It will also require looking beyond debt-financed investment. Attracting more FDI is one option. The other, inevitably, is building stronger domestic revenue bases so that Africa becomes less dependent on foreign sources of capital.

REFERENCES

Chen, W., D. Dollar, and H. Tang. 2016. “Why Is China Investing in Africa? Evidence from the Firm Level.” World Bank Economic Review, published online September 30.

Chen, W. and R. Nord. 2017 “A Rebalancing Act for China and Africa – The Effects of China’s Rebalancing on Africa’s Trade and Growth.” International Monetary Fund, African Departmental Paper Series, 2017.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2017. Regional Economic Outlook: Fiscal Adjustment and Economic Diversification. Washington, DC, October.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).