The United States is exceptional among wealthy nations in its high rate of child poverty. Even more so, the U.S. is known for its high level of deep child poverty—children in families with incomes less than half the poverty line.1

Child poverty is directly linked to elevated rates of chronic stress, obesity, food insecurity and malnutrition, housing insecurity, and elevated blood lead levels, among many other comorbidities that can lead to long-term health and educational challenges. Children growing up in deep poverty face additional risk factors for lifelong poor health, such as living in an unsafe community, having a parent with poor mental health, low social support, and higher parental stress, among other factors.2

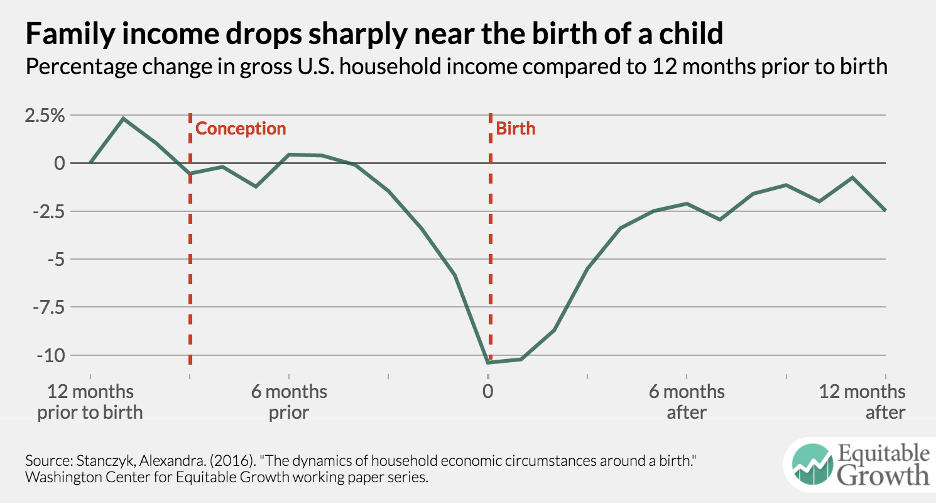

While child poverty is detrimental at any age, evidence finds that economic hardship during pregnancy and infancy is the highest across the life course. Average household income drops to its lowest level, and poverty jumps to its highest level starting in the final months of pregnancy, peaking at childbirth, and remains elevated through at least six months after birth.3 This period is also associated with extraordinary expenses such as car seats, cribs, diapers, as well as additional out-of-pocket medical and child care expenses. The perinatal period also corresponds with the most critical window of neurodevelopment, laying the groundwork for future health and well-being.4 Investments in economic resources during the earliest years of life have been shown to have lifelong impacts, including increased life expectancy, higher educational attainment, increased employment and earnings, and lower receipt of other public assistance benefits.5

Figure 1.6

Prescribing child cash transfers

One tool that has proven highly effective in addressing child poverty is universal child cash benefits (UCBs). As of fall 2024, there are 49 countries with active UCBs and nine with near-universal child benefits that cover all but the wealthiest families.7 An analysis of 15 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member nations with such programs finds that they reduce poverty among households with children by five percentage points.8 Child cash transfers have also been shown to improve the health and well-being of children more broadly.9 Universal and near-universal child benefits cost more in total benefits paid because they cover all or most of a population, but they are less administratively costly than child poverty programs that impose means tests or conditions on aid and by extension require government to incur the significant costs of enforcing these conditions. They also carry less stigma than narrowly targeted programs.10 As a general rule, they tend to have higher coverage rates, and as a result are more popular with electorates.11 Because of their success around the world, UNICEF and the International Labour Organization call child cash benefits “the foundational policy for child and social development.”12 A great deal of evidence finds that if one time frame were to be targeted for major poverty reduction it should be the critical perinatal period.13

During the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC), the United States joined other high-income nations with a near-universal, unconditional child cash benefit. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates the expanded CTC lifted 5.3 million people including 2.9 million children out of poverty and was central to bringing the child poverty rate to an historic low of 5.2%.14 Many other measures of child and family well-being improved during this time.15 After the expanded CTC expired, U.S. child poverty more than doubled.16

Building on the success of the short-lived federal program, ten states and the District of Columbia have adopted refundable CTCs for families with no or low earnings.17 Some state programs are available only to the poorest children while others include the middle class (and one is universal).18

Michigan’s public-private prenatal and infant cash prescriptions initiative

Inspired by the expanded CTC and the global evidence on child cash transfers, Rx Kids was launched in January 2024 in Flint, Michigan as the nation’s first citywide prenatal and infant cash prescription program. An academic-nonprofit partnership supported by the State of Michigan and philanthropy, the initiative is led by Flint-based Michigan State University Pediatric Public Health Initiative, in collaboration with Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan. The program is administered by GiveDirectly, an international leader in delivering unconditional cash transfers. Funding has been provided through a mix of private philanthropy, led by the C.S. Mott Foundation, and public investment from the State of Michigan.

Rx Kids provides all expectant mothers in the City of Flint with a one-time prenatal prescription ($1,500) after 20 weeks gestation, and all families with infants receive 12 monthly prescriptions of $500 after birth, for a total of $7,500. The community-wide program builds on innovative smaller-scale pilot programs, such as the Bridge Project, and the Abundant Birth Project that provide pregnant mothers and families with infants with cash support.

This early childhood initiative has a few key design principles. It is 1) universal, serving all pregnant people and infants within a very poor city (an approach known as “targeted universalism”); 2) unconditional, meaning families are not required to fulfill requirements to receive support; and 3) predictable, meaning all families get the same benefit and virtually all other forms of public assistance are protected.19 Program take-up so far is estimated to be nearly 100% of eligible newborns.

The State of Michigan leveraged the flexibility of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant dollars to support this novel effort. TANF funding is used through a mechanism referred to as “non-recurrent short-term benefits” (NRST) that can be used to deliver up to four months of cash payments to families experiencing acute economic hardship.20 Rx Kids defines the end of pregnancy and childbirth as a period of acute economic hardship for families. Importantly, NRST payments are not considered formal cash assistance by TANF, and do not trigger time limits or work requirements. They can be made concurrently with cash assistance and other benefits and can be given to non-TANF participants. Considered a gift from GiveDirectly, the cash prescriptions do not impact income eligibility for most other means-tested benefits.

Rx Kids has so far prescribed over $4 million to over 1,000 families, reaching almost every newborn born in the City of Flint. In an initial survey of 112 of these families, respondents report improved family financial security and spending cash prescriptions on baby supplies, food, rent, utilities, and transportation.21 Survey research with over 1,000 respondents compares cash prescription recipients to non-recipients, and further indicates improved housing stability (no evictions among low-income families), greater food satisfaction, decreased postpartum depression and improved maternal well-being—as well as increased positive parenting and trust in government.22 Preliminary maternal infant health outcomes reveal more prenatal care, more adequate prenatal care (earlier and more often), less smoking in the third trimester, and a decrease in extremely premature and low birth weight babies. These findings are consistent with the extensive evidence base and yield significant return on investments and societal savings.

This public-private initiative is now planning expansion to other low-income Michigan communities in early 2025, with significant bipartisan support. It was highlighted as a model program in a cross-partisan plan to support families with young children by the Convergence Collective, an initiative led by conservative thought leader Abby McCloskey.23 At the program’s public launch, Governor Gretchen Whitmer said that “Rx Kids will give every new mom in Flint the freedom and flexibility to raise their babies while paying the bills and putting food on the table.” Republican State Senator John Damoose says that with “Rx Kids, families are free to choose what best meets their needs. It cuts down on all the government red tape of other programs that seek to monitor the poor and tell them what they can and can’t have.” The partnership also has direct bipartisan links to national policy debates. Vice President Kamala Harris based her popular proposal for a $6,000 newborn tax credit to families on the program. Vice President-elect JD Vance is also on the record in support of a significantly expanded Child Tax Credit.

Expanding a prenatal and infant cash prescription nationwide

Based on the success of Michigan’s public-private initiative, there has been interest to expand a prenatal and infant cash prescription program to other states and nationally. A national program could cover all pregnant people and all families with infants. It could follow the (near universal) approach of the expanded Child Tax Credit in covering all but the highest-income families, thus ensuring efficiency, high rates of coverage, strong public support, and low stigma. Such a program could be administered as a new social program or through the tax code, an approach that history suggests offers political benefits that help with successful passage and sustainability.24

Alternatively, a national program could expand to poor communities across the nation, using a “targeted universalism” approach, as has been done thus far in Michigan. There is a good deal of reason to target programs like this to poor communities. Children growing up in poor communities—even those with higher incomes—experience a host of challenges not faced by those growing up in higher-income places. What’s more, many persistently poor rural and urban communities alike have long histories of social and economic inequality and disinvestment.25 Yet many tools meant to improve conditions in poor communities have proven ineffective at improving the well-being of poor residents.26 A place-based program of prenatal and infant cash prescriptions would have the secondary benefit of injecting money into local economies. Another benefit would be the potential to serve both urban and rural communities equitably, whereas with many social services, rural communities are often underserved because of lack of scale and infrastructure.

A national program of prenatal and infant cash prescriptions could be financed through a combination of TANF block grant dollars allocated by states, as has been done in Michigan, and a relatively modest amount of additional federal funding. There is widespread agreement that states often use the flexibility of TANF to balance their state budgets or as a funding stream for new programs that have little to do with assistance to needy families. In some states, money flows to programs that are proven to be ineffective, such as marriage promotion and abstinence-only sex education. More broadly, nearly every state diverts some amount of TANF money to early childhood education, the child welfare system, or refundable tax credits—priorities that could be funded through other revenue streams if there were stricter guardrails around the eligible uses of TANF dollars. Nationally, under 25% of federal TANF dollars and state matching “Maintenance of Effort” (MOE) funds today are spent on cash assistance, and many states devote a far smaller share toward this purpose.27 As in Michigan, TANF block grant dollars could be used by states to leverage the NRST provision and fund the first four prenatal and infant cash transfers for lower-income families ($1,500 prenatal payment and three monthly infant payments of $500).28

Table 1 estimates the cost for various scenarios of a national program, using five-year estimates from the American Community Survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau and publicly available vital statistics on births and payer-type from birth certificates contained in the CDC WONDER database. Relevant data for counties with populations below 100,000 are not individually available through the CDC WONDER database. For these counties, births and Medicaid-paid births were estimated by taking the proportion of women of childbearing age in the county compared to the state overall and applying that to the number of births in the state. These estimates relied on the proportion of births funded in the state to determine how many births were covered by Medicaid in the county.

Estimated costs assume that all families receive the full $7,500 benefit and also assume 10% administrative outlay. These estimates are not meant to be definitive, but rather to give a provisional range of the costs of national expansion of a prenatal and infant cash prescription program 1) nationally and 2) in communities with high child poverty rates (using counties). The federal government could incentivize states to adopt a program by making additional funds available. The federal government could also act to exclude prenatal and infant cash prescriptions from impacting other public assistance programs.

|

Total births |

Proportion of all U.S. births |

Cost covered by TANF ($ billions) |

Total cost ($ billions) |

||

| Counties with child poverty rate above: | |||||

| 25% | 469,619 | 13.2% | $0.84 |

$3.87 |

|

| 20% | 1,121,990 | 31.5% | $1.86 |

$9.26 |

|

| 15% | 2,125,770 | 59.7% | $3.24 |

$17.54 |

|

| All births | 3,557,994 | 100% | $4.76 |

$29.35 |

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on CDC WONDER Database, 2023 data, and American Community Survey, 5-year estimate (2018-2022), U.S. Bureau of Census. Cost figures include cash transfer costs plus 10% administrative costs.

As shown in Table 1, national expansion of prenatal and infant cash prescriptions to all families with an infant would carry an annual cost of $29.4 billion, of which up to $4.8 billion could be paid for with TANF block grant dollars. Expanding only to extremely poor counties with child poverty rates above 25% nationwide would cover the 13.2% of all U.S. births in the poorest counties and would cost $3.9 billion, $842 million of which could be covered by TANF. Focusing expansion on counties with child poverty rates above 15%—which would cover three in five U.S. births—would cost just $17.5 billion, $3.2 billion of which could be paid for with TANF. As a point of comparison, the annual cost to the federal government in foregone revenue of the home mortgage interest deduction is roughly $30 billion.29

In summary, for an annual investment ranging from $3.9 billion to $29.4 billion, the United States could take a meaningful step toward eradicating deep infant poverty nationally or in very poor communities across the country. The national expansion of prenatal and infant cash prescriptions would be a low-cost yet high-value investment.

Conclusion

Child poverty is a root cause of numerous maladies, and it is most severe around the birth of a child. Prenatal and child cash benefits have been successfully implemented all over the world and are a proven strategy for preventing poverty and improving maternal and infant health. Built on this global evidence and the success of the expanded CTC, Rx Kids launched as the nation’s first targeted universal and unconditional prenatal and infant cash prescription program. With minimal administrative capacity, the program has considerable potential to help eliminate deep infant poverty and improve health outcomes in one of the poorest cities in the nation and is rapidly spreading to other low-income Michigan communities.

The national scaling of a new program of prenatal and infant cash prescription has the potential to secure bipartisan support, and could tap into an existing, sustainable funding stream in TANF that is underutilized. Through the reappropriation of TANF dollars and a modest additional investment by the federal government, families across the United States—and especially those in persistently poor communities—can welcome a new baby with the financial stability to ensure a lifetime of health and opportunity.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This memo was produced by Room 1, a working group linked to Sustainable Development Goal 1 on No Poverty, convened as part of the 17 Rooms global flagship in 2024. 17 Rooms is a platform for advancing the economic, social, and environmental priorities embedded in the world’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The initiative is co-hosted by the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution and The Rockefeller Foundation. In 2024, each Room was asked to develop and advance a big idea—a practical action or mechanism that could make a material difference to some aspect of the world’s 17 SDG outcomes by 2030.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. Our mission is to conduct in-depth, nonpartisan research to improve policy and governance at local, national, and global levels. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or the funders mentioned below.

The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation is a donor to the Brookings Institution. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in the absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2. A Demographic Portrait of Child Poverty in the United States. In: Duncan G, Menestrel SL, editors. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 7]. p. 41. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246.

- Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce Child Poverty, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix D: Technical Appendices. In: Duncan G, Menestrel SL, editors. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2019 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. p. 291. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246; Ekono M, Jiang Y, Smith S. Fact sheet: young children in deep poverty [Internet]. New York City: National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; 2016 Jan [cited 2024 Nov 6] p. 11. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578993.pdf; Edin KJ, Shaefer HL. $2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. 1st ed. HarperCollins Publishers; 2015. 240 p.

- Hamilton C, Sariscsany L, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Experiences of Poverty Around the Time of a Birth: A Research Note. Demography. 2023 Aug 1;60(4):965–76.

- Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. Why do we focus on the prenatal-to-3 age period?: Understanding the importance of the earliest years [Internet]. Child and Family Research Partnership, Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin; 2021 Jan [cited 2024 Nov 7]. Report No.: B.001.0121. Available from: https://pn3policy.org/why-do-we-focus-on-the-prenatal-to-3-age-period-understanding-the-importance-of-the-earliest-years/#:~:text=Our%20health%20and%20wellbeing%20prenatally,substantial %20challenges%20during%20these%20years

- Barr A, Eggleston J, Smith AA. Investing in Infants: the Lasting Effects of Cash Transfers to New Families. Q J Econ. 2022 Sep 20;137(4):2539–83; Bailey MJ, Hoynes H, Rossin-Slater M, Walker R. Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment? Large-Scale Evidence From the Food Stamps Program. Rev Econ Stud. 2024 May 9; 91(3):1291–330

- Stanczyk AB. The dynamics of household economic circumstances around a birth [Internet]. Washington DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth; 2016 Oct [cited 2024 Oct 22] p. 67. (Washington Center For Equitable Growth Working Paper Series). Available from: http://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/income-volatility-around-birth/.

- Shaefer HL, Hanna M, Harris D, Richardson D, Laker M. Protecting the health of children with universal child cash benefits. The Lancet. 2024. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140673624023663?dgcid=author.

- Richardson D, Harris D, Behrendt C, Winder-Rossi N, Costa Santos A, Obubo T. The promise of universal child benefits: the foundational policy for development [Internet]. Geneva: ILO, UNICEF, and Learning for Well-Being Institute; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 25. Available from: https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/Media.action?id=19447; ODI/UNICEF. Universal child benefits: policy issues and options. [Internet]. New York and London; 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 219. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/universal-child-benefits-2020

- Shaefer et al., “Protecting the Health,” 2024.

- International Labour Organization. World social protection report 2024-26: Universal social protection for climate action and a just transition [Internet]. 1st ed. Geneva: ILO; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 7]. Available from: https://researchrepository.ilo.org/esploro/outputs/report/995382292502676.

- ODI/UNICEF, Universal Child Benefits, 219.

- Richardson et al., The Promise of Universal Child Benefits, 25.

- Barr, Eggleston, and Smith, Investing in Infants, 2539–83.; Bailey et al., Is the Social Safety Net a Long-Term Investment?, 1291–330.

- Burns K, Fox L, Wilson D. Census.gov. [cited 2024 Nov 7]. Expansions to Child Tax Credit Contributed to 46% Decline in Child Poverty Since 2020. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/record-drop-in-child-poverty.html.

- Pilkauskas NV, Michelmore K, Kovski N, Shaefer HL. The expanded Child Tax Credit and economic wellbeing of low-income families. J Popul Econ. 2024 Dec;37(4):68.

- Shrider EA, Creamer J. Poverty in the United States: 2022 [Internet]. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2023 Sep [cited 2024 Nov 8] p. 67. (Current Population Reports). Report No.: P60-280. Available from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/ demo/p60-280.pdf.

- Butkus N. State Child Tax Credits boosted financial security for families and children in 2024 [Internet]. Washington DC: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy; 2024 Sep [cited 2024 Nov 8]. Available from: https://itep.org/state-child-tax-credits-2024/.

- Butkus, State Child Tax Credits, 2024.

- Shaefer HL, Hanna M. Playbook for replicating Rx Kids: Utilizing TANF and protecting public benefits [Internet]. MSU-PPHI/UM Poverty Solutions; 2024 Jul [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 10. Available from: https://rxkids.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Rx_Kids_TANF_Playbook.pdf

- Shaefer and Hanna, Playbook for Replicating Rx Kids, 10.

- Rx Kids. Rx Kids: A prescription for health, hope, and opportunity. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 8]. Key insights from the first citywide maternal and infant cash prescription program. Available from: https://rxkids.org/key-insights-from-the-first-citywide-maternal-and-infant-cash-prescription-program/.

- Hanna M, Shaefer HL. Results from Rx Kids Participant Survey & Maternal Wellbeing Research Study [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 17]. Available from: https://rxkids.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/RxKids_Research_Brief.pdf

- Convergence Collaborative on Supports for Working Families. In this together: a cross-partisan action plan to support families with young children in America [Internet]. Washington DC: Convergence Center for Policy Resolution; 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 28. Available from: https://convergencepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Convergence-Collaborative-on-Supports-for-Working-Families-Blueprint-for-Action.pdf.

- Greenstein, R. 2022. Next Steps on the Child Tax Credit. Economic Analysis report. The Hamilton Project. Brookings Institution.

- Edin KJ, Shaefer HL, Nelson TJ. The Injustice of Place: Uncovering the Legacy of Poverty in America. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Mariner Imprint; 2023.

- Isserman A, Rephann T. The Economic Effects of the Appalachian Regional Commission: An Empirical Assessment of 26 Years of Regional Development Planning. J Am Plann Assoc. 1995 Sep 30;61(3):345–64; Pender J, Reeder R. Impacts of regional approaches to rural development: initial evidence on the Delta Regional Authority [Internet]. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2011 Jun [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 73. (Economic Research Report). Report No.: 119. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=44857.

- Edin KJ, Shaefer HL. $2 a Day, 240 p; State Fact Sheets: How States Spend Funds Under the TANF Block Grant | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/state-fact-sheets-how-states-spend-funds-under-the-tanf-block-grant.

- Shaefer HL, Hanna M. Playbook for replicating Rx Kids: Utilizing TANF and protecting public benefits [Internet]. MSU-PPHI/UM Poverty Solutions; 2024 Jul [cited 2024 Nov 7] p. 10. Available from: https://rxkids.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Rx_Kids_TANF_Playbook.pdf

- Waters E, Minott O, Lautz A. Is it Time for Congress to Reconsider the Mortgage Interest Deduction? [Internet]. Washington DC: Bipartisan Policy Center; 2023 Nov [cited 2024 Nov 8]. Available from: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/is-it-time-for-congress-to-reconsider-the-mortgage-interest-deduction/.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).