Introduction

Tariffs, which are taxes on imported goods, are a key part of President Trump’s policy agenda. Pharmaceuticals are among the sectors targeted for tariffs. The administration has highlighted at least two objectives for tariffs on pharmaceuticals: securing U.S. drug supply chains by onshoring drug production and creating U.S. manufacturing jobs.

Understanding the impact of tariffs on pharmaceuticals is important because of the role prescription drugs play in the lives of Americans—61% of American adults (157M) and 20% of children (15M) fill at least one prescription each year through retail or mail pharmacies. Many of the same patients also get drugs administered in virtually all inpatient hospital stays. And millions of patients receive physician-administered drugs in the outpatient setting, for conditions like cancer or autoimmune diseases.

At the time of writing this article, there are two potential versions for sector-wide pharmaceutical tariffs. One is a 25% across-the-board tariff on pharmaceuticals. The other comes in the form of not yet defined reciprocal tariffs that would reflect any subsidies, including tax treatments, that foreign governments use to support specific domestic industries. These proposed tariffs would supplement tariffs already in place on all Chinese products, set at 20% for pharmaceuticals, and 25% tariffs on Canadian and Mexican products.

Although not spelled out in the announcements, the implied mechanism for accomplishing the administration’s goals can be summarized as follows:

- Tariffs push up the price that foreign products cost

- As that price increases, demand shifts away from the more expensive foreign products towards domestic products

- Domestic firms not only gain market share, but also increase their prices, further increasing their profits

- Increased profitability of domestic manufacturers then encourages domestic manufacturers to expand their capacity and new manufacturers to set up production in the U.S., increasing U.S. employment.

In this article, I discuss the extent to which this basic scenario is likely to play out as a result of contemplated tariffs by answering four questions:

- How might tariffs impact drug prices?

- Will tariffs lead to onshoring of pharmaceutical production?

- Will drug shortages result from tariffs?

- Will tariffs help de-risk drug supply chains from China?

To answer these questions, I first describe key structural dynamics in drug markets that will underpin my analysis. I distinguish between newer brand-name drugs, which are currently under patent protection, and generic off-patent drugs, which are inexpensive copies of older branded products that lost market exclusivity. I also describe the structure of the manufacturing part of drug supply chains and the role that FDA plays in overseeing manufacturing.

The analysis of the four questions suggests that prices will rise across drugs if tariffs are extended to India and Europe, but the rise will not be for the full amount of the tariffs. The tariff pressure and political considerations will lead to many onshoring announcements for branded drugs. But we should not expect to see the same for generic drug makers because the return on investment for such major capital investments will be too low and uncertain. In turn, tariff pressure for both domestic and foreign manufacturers of generics will test their already low margins, potentially leading to product discontinuations or cost cutting that erodes quality. Any production disruptions in the already fragile generic injectable markets are likely to result in shortages.

I conclude with a set of considerations for the Trump administration.

Prescription drug market dynamics relevant to tariff analysis

To understand how tariffs might raise drug prices or lead to drug shortages, I first lay out some industry dynamics: the distinction between generic and branded drugs, how drug supply chains are organized, and the role of FDA in manufacturing quality oversight.

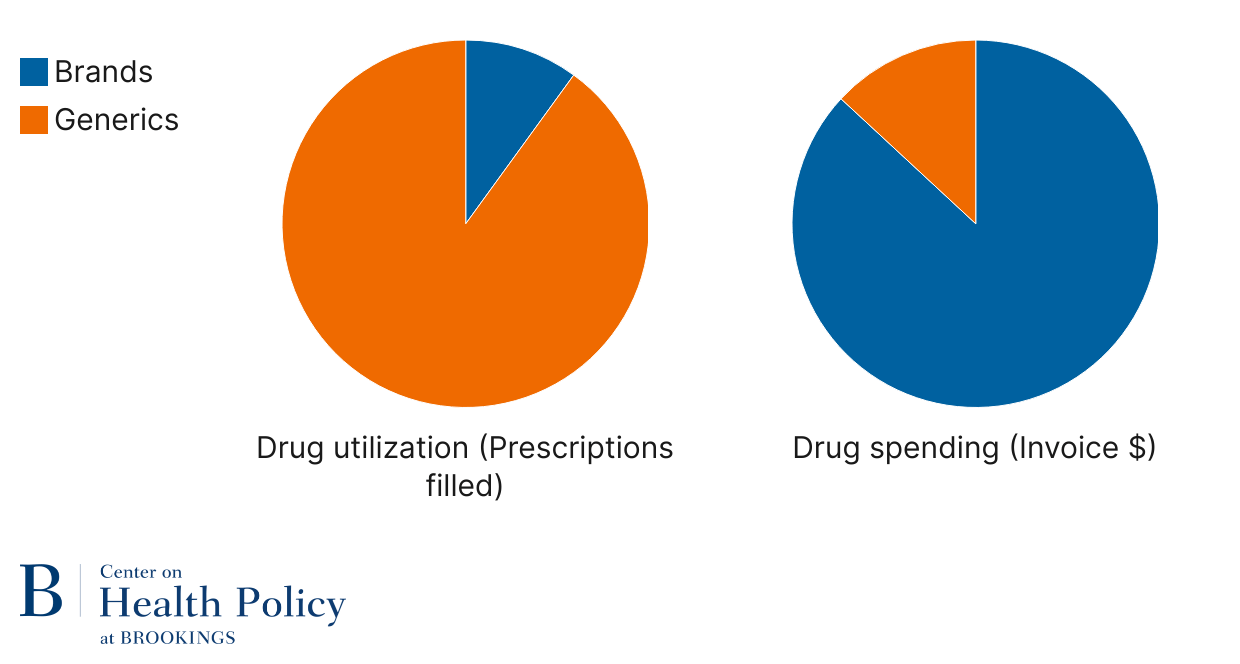

We spend money on brands but use generics

When new drugs come to market, they benefit from market exclusivity that prevents others from making copies primarily because of patents. A branded drug may need to compete with other brands, but the level of competition is lower than when they face exact copycats. Once market exclusivity ends, generic and biosimilar versions can come on the market: generic for small molecule drugs, and biosimilar for biologic drugs. Of the about 257 large-molecule biologic drugs, about 6% have biosimilar competition. Of the about 2,900 approved small drug molecules, about half have generic competition. Within a year or two of generic entry, prices drop precipitously leading the off-patent branded version molecule to exit the market. Because older drugs are effective for many conditions and because of their price, Americans primarily take small molecule generic drugs. Generics represent 92% of U.S. retail and mail pharmacy prescriptions (Figure 1). They also represent about three-quarters of volume (doses) in the smaller hospital setting. In turn, spending goes towards patent-protected small molecule and biologic drugs—over 87% of overall invoice spending in the retail setting is on branded drugs. Invoice prices do not account for various discounts on branded products, but even if those discounts were 25-50%, the wide gap remains—we use generics and spend on brands.

Figure 1: Role of generics in pharmacy drug spending and utilization

Source: IQVIA (2024), The U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report

Note: Retail and mail pharmacy spending and utilization; does not include physician-administered drugs

Drug supply chains are complex

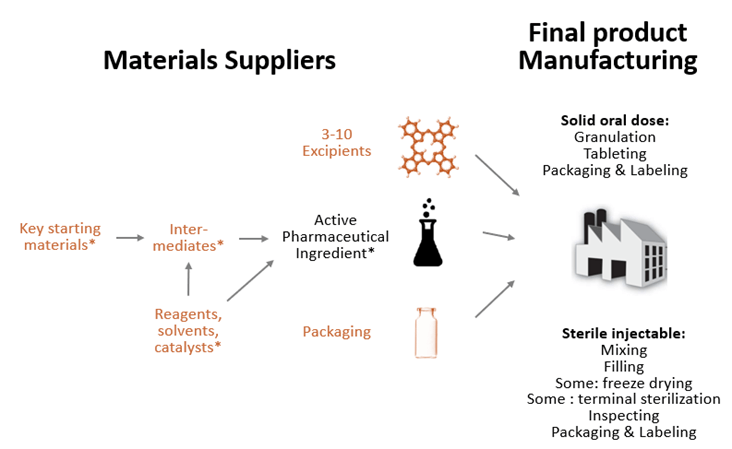

The drugs distributed at a pharmacy counter or administered in a hospital are finished dosage form (FDF) drugs. FDF drugs contain one or more active ingredient (API) and between 3 to 10 excipients that have no therapeutic effect but either serve as fillers, diluents, or otherwise affect functionality of the product, such as stability or dissolution rate (see Figure 2).

The API is product specific. It is the acetaminophen in Tylenol, semaglutide in Ozempic, or atorvastatin in Lipitor. API for small molecule drugs is chemically synthesized, often involving multiple steps, using a series of chemical reactions where key starting materials are transformed into intermediates and then API using various auxiliary agents that enable the chemical synthesis: reagents, solvents, and catalysts (see Figure 2). Biologic drugs are somewhat different in that the API step is complex but has fewer stages—it involves culturing the drug substance in living cells and then purifying that drug substance.

Figure 2: Typical drug supply chain for small molecule drugs

Note: Items marked in orange are not used exclusively in drug supply chains. For biologics, steps marked with * would be replaced with cell culture and purification, all done in one facility.

Relevant to supply chain resilience and onshoring costs is the fact that FDF can have different formulations, each using a different production process. Most of what consumers use are tablets and capsules, but many drugs are either injected or infused. There are also creams, oral solutions, drops, ointments, and other specialized formulations. Also relevant is that manufacturing processes for FDF can be specialized to type of formulation and type of drug, e.g., sterile injectables are made with very different machinery than oral dose products, some drugs are freeze-dried, some can be sterilized with heat, but others are made in a sterile environment, and some require dedicated lines or even buildings to prevent cross-contamination.

What is relevant for segment-specific tariffs is that only FDF and API products are specific to pharmaceuticals, with the rest of the supply chain (marked in orange in Figure 2) shared with other industries. Excipients, such as starch, lactose, or titanium dioxide, are used in foods and cosmetics. Key starting materials and enabling chemicals are all fine chemicals with many industrial uses.

Where drugs are made varies by type and stage

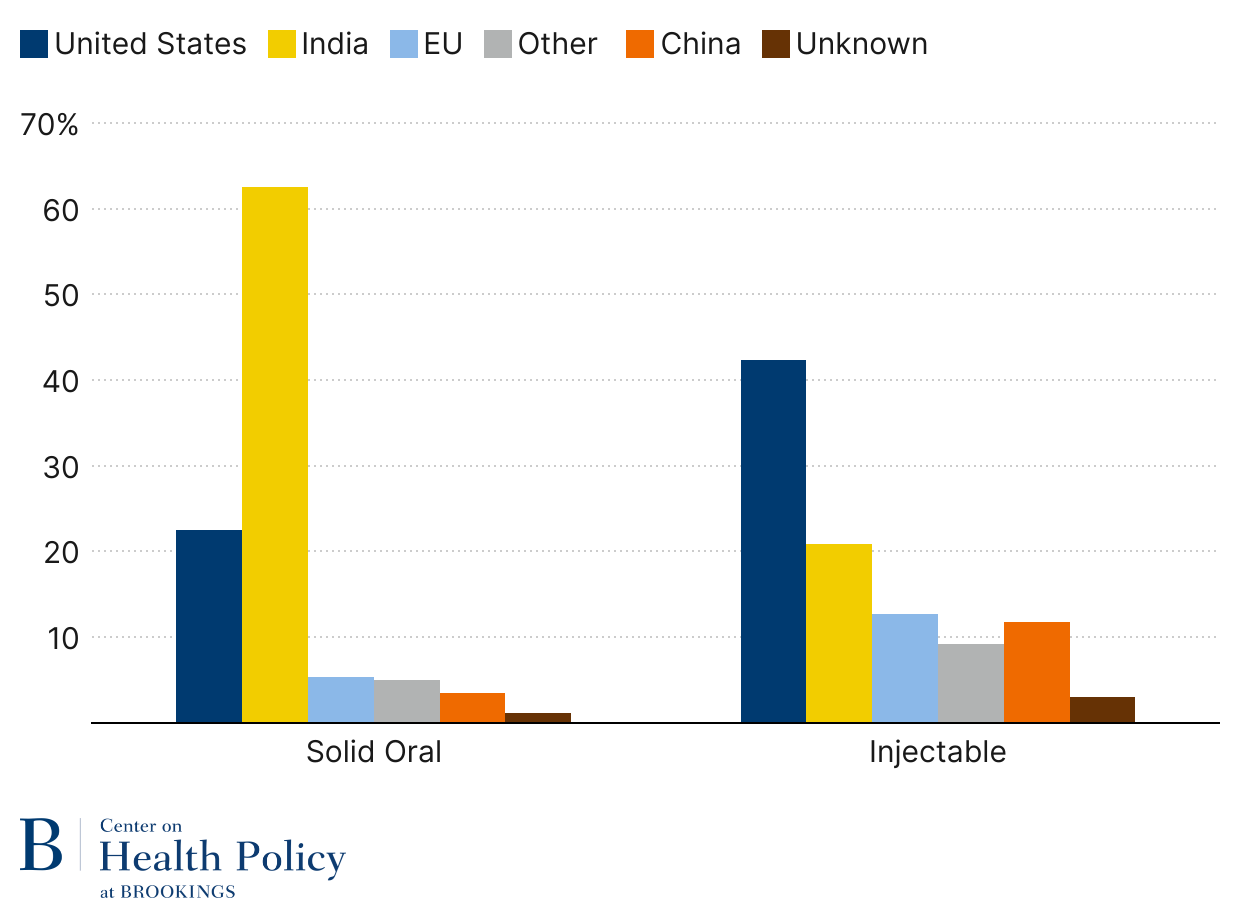

Generic solid oral dose drugs have the largest footprint with American patients. These drugs include statins for high cholesterol, multiple blood pressure medications, metformin for blood sugar control, levothyroxine for thyroid disorder, and SSRI drugs for depression and anxiety. About 187 billion generic drug tablets and capsules were dispensed in retail and mail pharmacies in 2024 (source data from Figure 3), equating to about 550 pills per person or 1.5 chronic medications.

As Figure 3 indicates, generic solid oral drugs are now primarily made in India. The U.S. makes 22% unit share of generic solid oral dose drugs, a big share of it controlled substances like opioids and ADHD medications, due to Drug Enforcement Agency requirements that those products are domestically produced. China represents a 3.5% unit share, which is less than Europe’s 5.4% unit share.

Sterile injectable generics, such as IV antibiotics, saline, chemotherapy agents, lidocaine, and epinephrine, are still largely made in the U.S. (Figure 3). Part of it has to do with the complexity of production relative to oral dose products and the much higher transportation costs for such drugs. But offshoring has followed, with India taking a leading role in the trend, currently at 20.9% unit share. China is almost on par with Europe when it comes to generic injectables, 11.8% and 12.7% respectively.

Figure 3: Generic drug volume by location (2024)

Source: USP Medicine Supply Map using IQVIA & USP data; published by permission from USP

Note: Solid oral dose volume is measured in tablets/capsules; injectables are measured in dispensing units (vials, syringes, or IV bags)

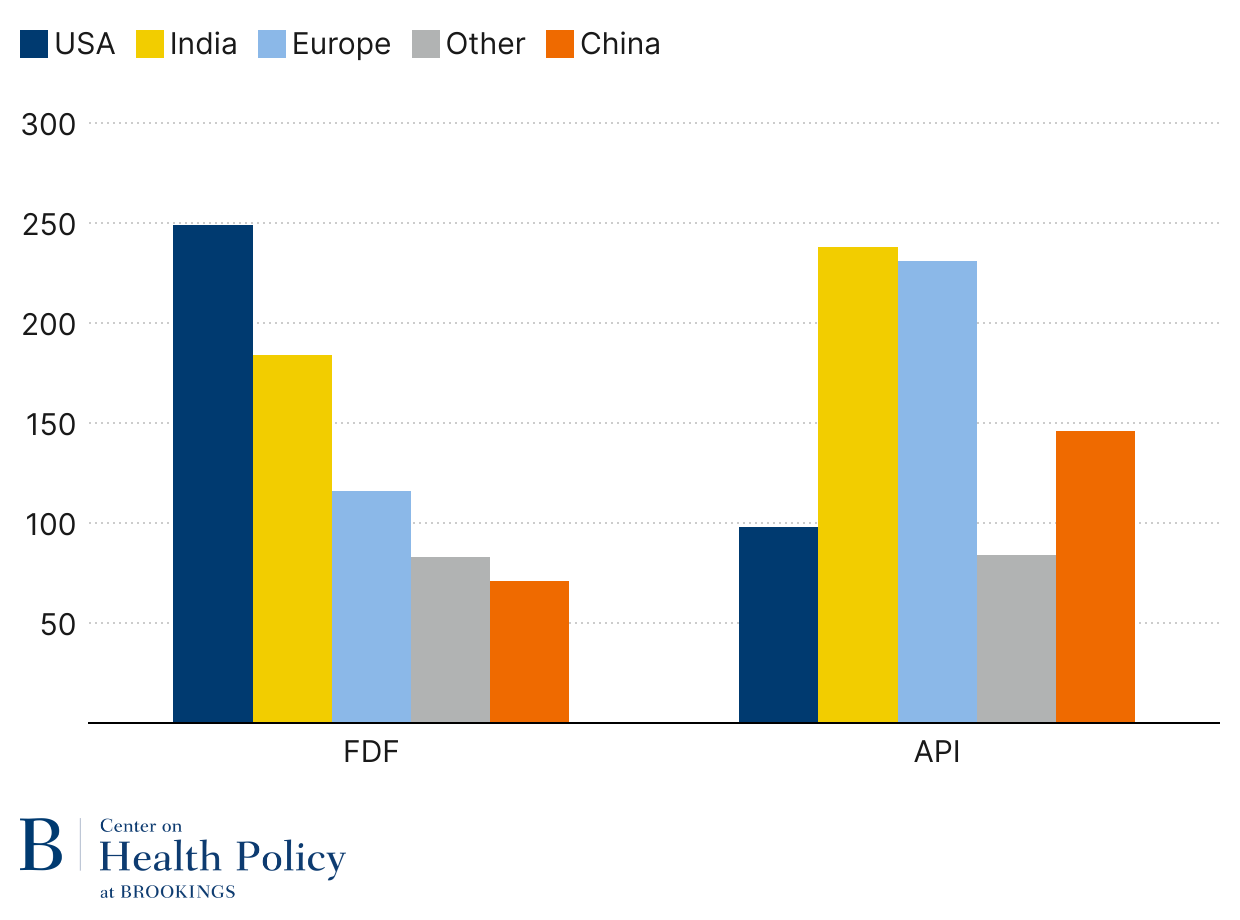

What is more difficult to ascertain is where API for generics comes from. Using FDA Generic Drug User Fee Act facility payment data, we can assess the location of facilities making FDF and API for generic drugs. A comparison between FDF and API is particularly instructive. As Figure 4 indicates, the U.S. has the highest share of FDF facilities, but its share of API facilities is less than half of what Europe and India have. Even China has more generic API facilities than the U.S.

Figure 4: Generic facilities by stage of production (2025)

Source: FDA GDUFA facility fee payments (2025)

Note: Some facilities produce FDF and API and are counted in both

It is important to note that Figures 3 and 4 show geographic distribution across all drugs, but geographic distribution for a given drug molecule may be far from what those figures represent. For example, underlying Figure 3 is U.S.-based Baxter with a 60% market share of 1L saline bags, U.S.-based Hospira with a 50% market share of injectable morphine, and Indian-based Intas with a 50% market share of carboplatin. Sources of API may vary across drugs or therapeutic classes. One analysis of 32 essential medicines found that steroids had API sourced almost exclusively in Europe, API for anticonvulsants came primarily from India, and production for API dialysis agents was split between the U.S. and Europe.

There is lack of visibility into where inactive ingredients and starting materials for API come from. Discussions with industry executives suggest that excipients largely come from the U.S. and other OECD countries, but China dominates the fine chemicals market which includes key starting materials and auxiliary chemicals needed for chemical synthesis of intermediates and APIs (Figure 2).

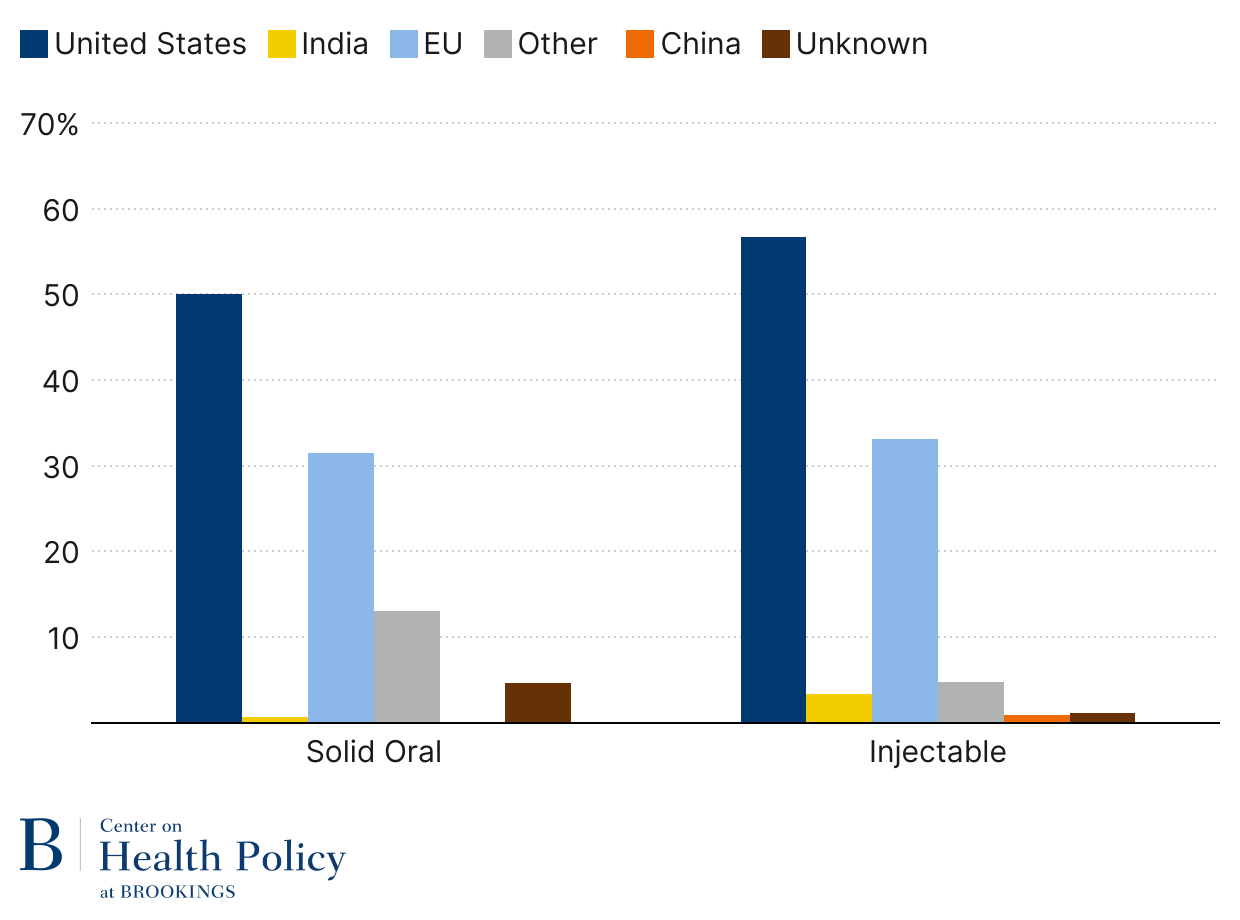

The FDF location picture (Figure 5 below) looks dramatically different for brands—the U.S. leads in both oral dose and injectable markets, India’s footprint is minimal, and China’s is basically nonexistent. Canada and Mexico (listed in Other) play a greater role in oral dose markets, with 1.8% and 2.4% share overall. Europe plays a significant role, with almost a third of units sold in both market segments. Data underlying Figure 5 suggests that Ireland leads with more than a third of Europe’s exports of branded oral dose drugs. Among injectables, leading European exports are Denmark, Germany, and Italy. The high declared value of branded drugs has helped make pharmaceuticals the largest European export category.

When interpreting these shares, it is important to keep in mind that they are aggregated across all branded drugs. For a given brand-name drug with no generic competition, it is quite likely that production is concentrated to one or two manufacturing sites, and chances are that the share of brands produced both in the U.S. and abroad is relatively small.

Figure 5: Branded drug volume by location

Source: USP Medicine Supply Map using IQVIA & USP data; published by permission.

Note: Solid oral dose volume is measured in tablets/capsules; injectables are measured in dispensing units (vials, syringes, or IV bags)

The picture on the brand API side (Figure 6) has a similar shift to that we see when we look at API generic—the U.S. has a smaller footprint than on the FDF side, Europe has a larger one, as does China. As with generic API data, the data are not volume weighted.

Figure 6: Confirmed API facility count for branded products by location

Source: Redica Systems; published by permission.

Note: Only includes facilities confirmed to make NDAs or BLAs based FDA compliance records

Active ingredient location is center stage for tariffs on pharmaceuticals

When goods enter a U.S. port of entry, they are classified using a standardized system called the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS). Importers classify their goods according to the HTS and declare their value or quantity. The applicable duty or tariff they then owed to the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is based on the HTS classification and the country of origin.

The determination of the country of origin and, therefore, the appropriate duty or tariff is not straightforward in that the country of origin is not necessarily where the product is imported from. Instead, the country of origin is determined by where substantial transformation of the product happened. In some cases, the substantial transformation is relatively obvious—cars made in Germany are a product of Germany, even if parts (engine, tires, airbags) come from other countries. In other cases, substantial transformation might be before the final product. For example, if Brazilian nuts are mixed with salt and packaged in Australia, they are a product of Brazil.

The country of origin for prescription drugs follows the nuts example more closely than the cars example. CBP has long ruled that mixing ingredients into the final drug form does not substantially transform the API and therefore the country of origin is the API source. This means that an FDF drug coming from India will pay the Chinese tariff rate if it contains API made in China. The determination for the country of origin is different for government procurement rules.

There are exceptions to the API-based country of origin, either because substantial transformation takes place elsewhere in the supply chain or because of trade agreements. Drugs that involve multiple APIs will have the mixing stage as the country of origin. The complexity of the production process can also shift substantial transformation up or down from the API stage. For example, processing of APIs not suitable for human consumption, as with purifying and freeze-drying vancomycin, has been ruled to constitute the FDF be substantial transformation. The rules for products under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) can also differ.

Nonetheless, it is quite reasonable to use the API production country as the country of origin for single-API drugs finished in countries other than Mexico or Canada.

Of note, however, is that these rules could change.

Manufacturing of drugs has strict manufacturing standards for good reasons

As we consider the response from firms to tariffs, whether it is in terms of cutting costs or onshoring their supply chains, it is important to understand the role of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

FDA plays a critical role in addressing a major information gap resulting from the patients’ and physicians’ inability to observe drug product integrity, not only before consumption, but also after. Not every drug works the same for every patient, and the patient’s condition or response to the drug may change over time for physiological reasons. Because of that, when a patient stops responding to blood pressure medication, the physician will think to switch the patient to a different drug without suspecting that the drug may not be manufactured properly.

FDA requires that manufacturers of approved drugs (brands and generics) follow regulatory standards for ensuring the identity, strength, quality, and purity of drugs. This set of standards, called the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP), covers a broad range of controls over how drugs are manufactured. This includes establishing strong quality management systems, ensuring quality raw materials, having written operating procedures, identifying and investigating product quality problems, and maintaining reliable testing laboratories. This framework evolved as a result of many crises and many hundreds of deaths of Americans exposed to contaminated or substandard drugs.

But as with any laws, enforcement is key.

To assure that manufacturers follow CGMP standards, new-to-market drugs (brands and generics alike) must establish that their production process can reliably replicate the drug matching the safety and efficacy claims made on the drug label. FDA generally establishes that through pre-approval inspections of API and FDF facilities, but FDA might forgo a pre-approval inspection if it has reliable information about the facility and processes from other sources.

Once the product is on the market, FDA conducts surveillance inspections to assess compliance with manufacturing processes and the integrity of products on the market. FDA also makes sure that any changes to the API or FDF production process do not alter the product’s safety or efficacy. FDA requires manufacturers to report manufacturing process or setting changes, the more consequential of which may require an FDA inspection.

How might tariffs impact drug prices?

Two main factors determine whether tariffs will increase prices: tariff exposure and the ability of manufacturers to pass on price increases.

Tariff exposure reflects the extent to which production of a given drug is exposed to various tariffs. For a brand-name drug, the exposure may be quite uniform because there is only one version of the drug on the market, so it may be produced at just one site. For a generic drug, the exposure may vary because there may be many generic versions of a drug.

In the context of tariff exposure, it is worth underscoring the importance of API location. Under the current CBP rules, the country of API manufacture is generally the country of origin for a single-API drug not made in Canada or Mexico.

The ability to pass on tariffs onto buyers will depend on how competitive the markets are, how constrained production is in the short term, and the extent to which there are contracts or government regulations that limit manufacturer’s ability to raise prices. These factors will differ for brand-name drugs, generic oral dose drugs, and generic injectable drugs. For that reason, my analysis addresses these groups separately.

Brand-name drugs

As Figure 5 indicates, most FDF volume for brands is already produced in the U.S., followed by production in Europe. Although no such data exists for brand API sources, the U.S.-Europe dominance likely persists.

Under the current rules, the tariff exposure for a branded drug made in Europe would depend on where the API is manufactured. An FDF drug made in Europe will have the U.S. as the country of origin if the substantial transformation takes place in the U.S. This scenario, probably not common for drugs shipped from Europe, illustrates how consequential country of origin might be for a brand-name drug with a high price point—if the API is made in the U.S., the tariff is zero, but if the API is made in Europe, and a 25% tariff applies, a $10K drug would owe a $2,500 tariff.

A drug finished in the U.S. will not pay tariffs on its final product, but it may still be exposed to tariffs on its ingredients. For a branded drug, the cost of goods sold is very low relative to the price so there would not be much price pressure from input cost changes on the product’s final price. What might change, however, is how firms use internal transfer prices for API. Firms use transfer pricing to minimize their tax burden and may transfer API that costs them $100 to produce at close to final finished price. A tariff on API would change that equation, putting downward pressure on the transfer price of API.

If the $10K drug is faced with a $2,500 tariff, how much will its U.S. price rise? It depends.

One factor influencing the level and form of tariff passthrough is the competitive landscape faced by the affected drug product. Although a monopoly on a molecule-level, a drug may face competition from other branded drug molecules treating the same condition. For example, Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy directly competes with Eli Lilly’s Zepbound. If most of Wegovy’s volume were subject to tariffs but the majority of Zepbound’s volume were not, then Novo would find it challenging to increase the effective Wegovy price to payers.

If both molecules have high tariff exposures, we could expect the impact to be through lowered rebates, not higher list prices. That is partly driven by Medicaid and Medicare inflation rebates, which manufacturers must pay if prices of their products rise faster than the consumer price index (CPI). Those rebates limit their passthrough through list prices.

In a scenario where a brand faces little competition, rebates are low so increasing list prices is the only way to pass through the tariff. Here, again, inflation rebates would limit passthrough beyond the CPI. Manufacturers would also be limited in their passthrough in the commercial market, albeit indirectly. A large swath of purchasers (entities such as certain types of hospitals, clinics, and affiliated retail pharmacies) are eligible for the so-called 340B program, which allows qualifying entities to obtain drugs at a discount pegged to the Medicaid inflation rebate. This means that every unit used by a commercial patient in a 340B entity will be subject to 340B rebates.

Political considerations may also dampen tariff passthrough. Experience from the Clinton era health care reform shows that political considerations can limit manufacturers’ willingness to increase prices. And currently there is a lot at stake for branded manufacturers who are interested in changes to Medicare drug negotiation and the 340B program.

Generic injectable drugs sold to hospitals and clinics

As Figure 3 indicates, 42% of FDF production for generic sterile injectables is already done in the U.S. These products would not face tariffs on their FDF, although they would face input cost increases if sourcing from abroad—quite likely given the small generic API footprint in the U.S. (Figure 4). With low margins and a high share of API in its cost of goods sold, a tariff on API will likely put upward price pressure.

Currently, at least 15% of generic injectable volume is facing tariffs—the 13% coming from China and more than 3% coming from Canada. But China represents a much higher share of API facilities than FDF facilities (Figure 4), suggesting that more products may currently be exposed to tariffs. For instance, it is often noted that China has a hold on API production of antibiotics.

Across the three market segments, GSIs face the greatest challenge in their ability to pass on price increases. One reason is immediate—group purchasing organization (GPO) contracts. All hospitals use GPOs to contract for sterile injectable generics used in inpatient settings, with those contracts locking in prices but not quantity. Hospitals not part of the 340B program also use GPO contracts to secure prices of generic injectables used in the outpatient setting.

Those contracts generally last one to three years and may limit price increases, unless courts consider tariffs as falling under force majeure—a standard provision in contracts that frees parties from contractual obligations because of an extraordinary event that prevents one or both parties from fulfilling contractual obligations.

Even if GPO contracts could be sidestepped, certain generic injectables would face another obstacle—Medicaid inflation rebates and the 340B program. The Medicaid program exposure for generic injectables is unclear, but the resulting 340B exposure can be significant, especially generic chemotherapy agents and so-called supportive drugs designed to protect the body from chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Solid oral dose generics

As Figure 3 shows, almost 80% of all the generic drug tablets and capsules we consume in the U.S. come from abroad. Given the small API facility footprint in the U.S. (Figure 4), it is unlikely that many or any of the imported products use U.S.-based API.

The unit share of products from China, Canada, and Mexico, around 3.5%, 2.5%, and close to zero, underestimates the exposure of existing tariffs. One reason is that China has a greater representation in API than with FDF. India imports about a third of API by volume, with around 75% of it from China.

For a given drug, the upward price pressure of current and potential tariffs will depend on the market share of the versions with tariffs and the capacity of non-exposed manufacturers to take on that volume. For this reason, even what appear limited share of Canadian products might matter. For example, if Teva’s Canadian-made amoxicillin has a large market share, buyers may not have less expensive options to turn to and, therefore, tariffs will put upward pressure on prices across all producers. If we see tariffs rolled out to Indian and European generics, the tariff exposure should be high across virtually all oral dose generic markets.

Unlike branded drugs and generic injectables, the ability of oral dose generics to pass on price increases to buyers is less constrained, except for markets with high Medicaid exposure, of which amoxicillin is one. In contrast to generic injectable markets, the retail generics market largely operates as a spot market, with few long-term contracts signed. Additionally, generic drugs are exempt from Medicare inflation rebates, unless only one generic is on the market. They also have much less exposure to the 340B program than brands and injectable generics.

Impact on buyers and payers

It is worth considering how increases in U.S. drug prices might affect buyers and payers.

Retail pharmacies buy generics on what is pretty much a spot market so any increase in prices will show up quickly in their acquisition costs. However, pharmacies are reimbursed based on contracted rates that are either a share of list price or fixed reimbursement rate. The impact will be immediate as prices rise, challenging pharmacy margins at least until contracts are renegotiated.

For hospitals and clinics, branded drug costs are passed to payers but there is a lag in reimbursement, e.g., Medicare has a six-month lag for the reimbursement rate to adjust to the average sales prices. For generics, hospitals are protected in the short run through contracts that GPOs negotiate with manufacturers. 340B hospitals are protected in the short run and the long run, but only for price increases above the CPI.

Exposure to increased prices varies by payer. As discussed above, Medicaid is protected above CPI, which means less so if the U.S. also experiences higher inflation. Medicare is protected above CPI for brands and single source generics. But any increase in prices up to the CPI will translate into higher government spending on drugs. Commercial plans will have limited protection through the end of the year when its pharmacy contracts and rebate agreements expire.

Increases in drug prices would probably be most visible to patients taking branded products because increases in list prices would directly translate into higher out-of-pocket spending for patients in high deductible plans or with high coinsurance rates. Patients taking generics would also notice quickly if they were in high deductible plans, but the impact would be less given the low generic drug price points.

The primary impact on patient pocketbooks would be indirect—premiums would likely rise as the payer spending on drugs increases. The impact would depend in large part on whether tariffs are expanded to drugs coming from Europe and India, with it expanding the tariff exposure. It is also worth noting that commercial payers would likely face the greatest upward spending pressure, not only because they do not face the kinds of protections that Medicaid and Medicare have, but also because prescription drugs make up a much more significant share of their medical spending than what is seen in Medicaid and Medicare.

Will tariffs lead to onshoring of pharmaceutical production?

To understand how tariffs affect manufacturing location decisions, it is best to use the framework that firms use to make any investment decision: Is the expected net present value (ENVP) greater than ENVP in locating (or maintaining location) in other markets?

Tariffs can positively improve relative ENVP if:

- Firms expect an increase in profits from locating in the U.S.

- Firms expect the incentive will last long enough to ensure a positive return on investment

- The costs to enter the market are low enough relative to future profits to ensure a positive return on investment

- The ENVP of the current position worsens.

Brand-name drugs

The discussion of tariffs in the previous section suggests that the economic incentive for onshoring can be significant for a brand-name drug with a high profit margin. If tariffs were to be expanded to Europe, having both API and FDF production there for a given drug would prove costly. Using the example of a $10K drug with $100 API, a 25% tariff on a $10K final price drug would translate into a twenty-six-fold effective API price (from $100 to $2,600).

There is also a less direct incentive to onshore—the political value of onshoring. Manufacturers of branded drugs have several key policy priorities: revising the Medicare drug negotiation program, reforming the 340B program, and pharmacy benefit manager reforms. Unlike tariff policy, which could change easily, any changes to Medicare drug negotiation or the 340B program would be long-lasting.

And what would it take to onshore?

For tariff purposes, perhaps the easiest path to onshoring would either be through a domestic contract manufacturer or purchasing existing infrastructure. We could also see a shift in existing U.S. production lines, to the extent that U.S. manufacturing sites make product not just for the local U.S. market but also for other countries. None of these approaches are costless or immediate—they require technology transfers, which can take a year or more and are limited by the availability of suitable production lines. But they are cheaper and faster than breaking ground on new sites.

Building a manufacturing plant can cost upward of a billion dollars. Recently infrastructure expansion includes Eli Lilly’s $23 billion investment into multiple facilities Merck’s $1 billion plant, $4.1 billion Novo Nordisk’s fill-and-finish plan expansion, Johnson & Johnson’s $2 billion biologics facility, FUJIFILM $1.2 billion expansion of a biotechnology site, and Amgen’s $1 billion biotechnology site expansion. Site construction costs may further increase with steel tariffs because industrial construction relies heavily on steel, now subject to 25% tariffs. The same concern applies to manufacturing equipment, which is all stainless steel.

There are several factors in determining a location for a new facility. One factor is permits. Conversations with industry executives reveal that building a manufacturing plant from the ground up generally takes three to five years, much of it related to the local permitting process for utilities, disposal, and other community concerns. What makes local permits challenging is that they can vary dramatically across locations, increasing the risk for potential delays.

Another factor in determining location is workforce. Much of recent U.S. pharmaceutical infrastructure investment has been limited to specific localities, primarily North Carolina and Indiana, not only because of low land prices and firms’ experience with local permitting, but a local, educated workforce, developed in partnership between industry and local universities. The jobs that these kinds of plants create differ from older manufacturing jobs. They require a highly skilled and educated workforce—more engineers and scientists than high school graduates.

Generic drugs

The cost to construct a manufacturing site is not any different for branded drugs than generic drugs. What matters more is the type of technology the drug is using. The complexity of API facilities will depend on the complexity of molecules involved, whether simple small molecules, complex ones, or biologics. A fill-and-finish facility is the same for brands and generics, no matter how complex the API.

There are two main reasons why generic manufacturers have been increasingly investing in India for small molecule API and FDF. One is cost. You can build a facility in India for a fraction of what it costs in the U.S. because of much cheaper land, labor, and parts. You can build a facility much faster because there are far fewer local permits holding up the process. The other reason is a lower opportunity cost—generic drugs have low margins, so the cost of a shutdown due to manufacturing quality or infrastructure problems is less than for a branded drug.

But could tariffs change the onshoring calculus the way it changes incentives for branded manufacturers? The short answer is no.

To manufacturers of generic drugs, incentives for onshoring production are significantly lower than for manufacturers of branded products. The $10K drug example with $100 API is illustrative here. Whereas the effective increase of API cost was 26 times for a brand (from $100 to $2,600), a generic with the same API cost but a much smaller margin (say 20%) will face an effective API cost increase of 30% (from $100 to $130).

The margin upside from locating in the U.S. will be limited for other reasons. First, domestic manufacturers obtain a big share of their inputs from outside the U.S. Even if those inputs had U.S. options, those options would likely be more expensive than the foreign ones, especially on the fine chemicals side. In the meantime, generic manufacturers will keep facing price pressure from the consolidated buyer base, and unless Congress acts, some generic drugs, including those made domestically, will continue to be limited in their ability to pass on legitimate cost increases.

The strategies that branded manufacturers could use in the shorter term, like contracting with third parties or making production more local, are much less likely to work for generic manufacturers. For one, U.S. generic drug facilities likely export very little, meaning there is little to be gained from reorganizing which plants make which products. Using data supporting Figures 3 and 6, we calculate that the capacity needs for onshoring generics would be immense, with capacity needs for generic pills 27 times larger than for branded pills. Any available contract manufacturing capacity would likely go to branded products first, given their ability to pay.

Given the value of onshoring to brands, generic manufacturers would easily be outbid for any available capacity. Access to capital would also prove a challenge given the price tag involved and the financial situation of many generic firms. A branded company that has been heavily investing in U.S. infrastructure is Eli Lilly, with $37B in profit in 2024. In comparison, Amneal had a $117M loss in 2024, Sandoz made $1M, Hikma made $612M, and Teva lost $1.6B.

Given the uncertainty about the duration of tariffs, it is not clear that the long-time horizon necessary for capital investments is favorable for capital-intensive onshoring of what will continue to be low margin products.

Will drug shortages result from tariffs?

Drug shortages happen when supply chains cannot absorb shocks to supply or demand. To understand the potential for shortages, we need to understand whether tariffs could contribute to supply disruptions and whether drug markets are sufficiently resilient to absorb any such supply disruptions.

As described in the pricing section, prescription drugs face various constraints in their ability to pass on cost increases to its buyers, especially in the hospital setting. In this context, we may see the profitability of drugs, especially sterile injectable generics, to be challenged.

A firm facing margin pressure may work to source from a lower cost environment, but in the short term, the firm faces two options: further cut costs or exit the U.S. market.

The potential for further cutting costs is concerning because it can adversely affect product quality if cost cutting happens through equipment maintenance, quality of materials, process control, or quality assurance. If problems arise, for example, the product is contaminated with other API, bacteria, or metal shavings (all actual examples), manufacturers may temporarily shut down or slow down production, leading to a potentially dramatic drop in output. But if FDA oversight is concurrently weakened, economic theory and experience suggests we should expect product quality to decrease.

Another bad option is to discontinue production of the unprofitable drug. Historically, discontinuations have not been a major driver of shortages, partly because manufacturers have tended to decrease production before exiting, leaving a more vulnerable market but not triggering a shortage. But companies may be less shy about exiting if they can blame tariffs they cannot control. Discontinuations of production by manufacturers with smaller shares can occur in close succession, magnifying the impact on each.

Can markets adjust to temporary shutdowns and permanent discontinuations so that shortages do not result?

Extensive experience in the generic sterile injectable market suggests that the generic injectable market is particularly slow to adjust to supply shocks. Part is lack of capacity in the short term and lack of fungibility in the production process—cytotoxic drugs cannot be made on antibiotic lines or a drug that comes in vials cannot be put into IV bags. With long time frames to expand production and the lack of incentives to do so for generic sterile injectables, it is clear that—should supply disruptions occur in sterile injectable markets—shortages will follow.

Will tariffs help de-risk drug supply chains from China?

De-risking drug supply chains from China is very different than onshoring pharmaceutical production in the U.S. As described above, the exposure of drug supply chains to China is primarily in small molecule drugs through key starting materials and auxiliary materials. Conversations with industry executives suggest that China dominates the fine chemicals industry of which those inputs are part. Exposure of drug supply chains to China diminishes as production shifts from chemicals to drug manufacturing, but both API and FDF footprint have been growing.

Much of the exposure to China is indirect because much of the API and FDF production for generics takes place abroad. This means that it is the Indian and European companies that source chemicals from China. The governments of those countries have recognized that exposure and have put forward plans to reduce their dependence on China. Since 2020, India has actively been decreasing its reliance on China, largely through subsidies for infrastructure. The EU’s proposal has not yet been implemented but it intends to use subsidies to strengthen supply chains of select critical medicines, including antibiotics, which are known to have high China exposure.

The impact of tariffs on exposure to China depends on how they are structured.

China-only tariffs, or for that matter, a substantial wedge between China tariffs and other locations, have a unique impact on drug supply chains—they drive API production away from China to other locations. We might see a lot more friendshoring than reshoring if China-only tariffs are in place because low-cost options would exist.

In turn, sector-wide pharmaceutical tariffs could end up being counterproductive to de-risking efforts. One reason is that China exposure is primarily indirect, through other countries, and, therefore, tariffs on U.S. imports have no impact other than on API sourcing. Decreasing reliance on countries actively subsidizing de-risking initiatives means that the de-risking burden would need to shift to the U.S. Decreasing U.S. exposure to inexpensive Chinese fine chemicals would require a much broader strategy, well beyond the reach of pharmaceutical tariffs.

Considering next steps

Many observers will raise higher prices as an argument against tariffs. I take a more nuanced approach—we may have to accept higher prices for generic drugs if we want to have resilient supply chains.

However, I am worried that without further policy interventions, tariffs will not make supply chains more resilient. In fact, I am worried that the resilience of many supply chains, already weak for drugs like sterile injectable generics, will be significantly challenged.

Of course, the scope and level of tariffs will matter for how they affect specific markets in the short and long run. It will also depend on the structure of specific markets, with generic sterile injectable drugs at the most risk of disruption that might lead to shortages. Most importantly, the impact will depend on what other policy actions the administration and Congress might take to buffer the supply chain.

This paper is not intended to provide a comprehensive policy proposal for how to supplement the tariffs, but four main themes arise if the administration intends to move forward with across-the-board pharmaceutical tariffs affecting branded and generic drugs alike.

First, the administration should add pressure valves to prevent shortages. This is important because generic margins will be threatened, leading manufacturers to pull unprofitable products from the market. A big factor here is the limited ability of manufacturers to pass on tariffs onto buyers. Some of it has to do with private contracts, but it also relates to the congressionally mandated Medicaid inflation rebates on multisource drugs and the spillover they have on sales to 340B entities. Another policy to consider is substantially delaying tariffs on API used by domestic manufacturers, with it improving their profitability.

Second, the administration should increase, not decrease, FDA’s capacity to oversee drug manufacturing. One reason is that generic drug margin squeeze may lead manufacturers to cut costs by cutting corners, which, especially if coupled with weakened FDA oversight, could lead to a higher rate of substandard drugs being shipped to American patients. Another reason is that any onshoring of facilities will increase the existing demand for FDA services—services that are critical for assuring that facilities are set up to consistently manufacture products to specification, with that assuring the safety of drugs that American patients take.

Third, the administration should directly finance generic drug onshoring, in recognition that tariffs alone will not create a sufficiently strong business case to attract private investment in pharmaceutical infrastructure. Identifying sources of funding for such initiatives can be challenging. However, here, branded drug tariffs will likely generate significant revenue, which could then be used to stimulate onshoring of generics.

The fourth point is perhaps the most challenging—de-risking drug supply chains from China will be significantly more challenging, if not counterproductive, without collaboration with India and Europe.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This project was conducted with support from the Gary and Mary West Health Policy Center. I would like to thank Paris Rich Bingham, Austin Grattan, and Rasa Siniakovas for their research assistance and USP Medicine Supply Map and Redica Systems for providing key data. I would also like to acknowledge helpful discussions with Carlo di Notaristefani, Alessandro Gagnoni, Anthony Maddaluna, Casey McCormick, Kerri McCullough Wood, Eric Percher, Dave Schoenecker, and Andy Wilson. I also thank Richard Frank and David Wessel for helpful comments on this manuscript.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).