Is the Hastert Rule dead? Speaker Denny Hastert coined his eponymous rule in 2003 when he declared that the “job of the Speaker is not to expedite legislation that runs counter to the wishes of the majority of the majority.”

Some are calling last night’s House vote (extending fifty billion dollars for disaster relief in the wake of Hurricane Sandy) a harbinger of the Hastert Rule’s coming demise. That bill involved what we might call a Hastert Rule violation, a roll call vote on which a majority of the majority party votes against a bill, but it passes. On the vote to pass the Sandy relief bill, just 49 Republicans joined all but one Democrat to pass the bill. In the parlance of many legislative scholars, the majority party was “rolled,” a strict no-no for a leadership said to be guided by Hastert’s rule. Coming on the heels of the New Year’s Day fiscal cliff vote that passed with only 85 GOP votes, one might reasonably ask whether the days of the Hastert Rule are numbered.

It’s too early to know whether Speaker Boehner will continue to violate the Hastert rule. Instead, I’ll offer some brief thoughts on the recent past and potential future of the Hastert Rule.

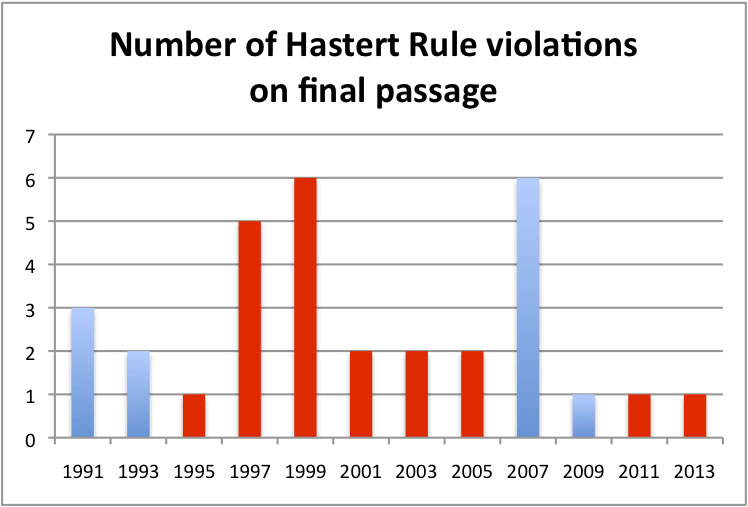

First, the logic of the Hastert Rule predates Denny Hastert. The basic premise of the rule—that House leaders will use their leverage over the floor agenda to keep measures off the floor that might divide the majority party—has guided House majority party leaders at least since the early 1980s. As Barbara Sinclair and Steve Smith documented some years ago, Democratic party leaders transformed the use of special rules in the 1980s and early 1990s to more aggressively structure votes on the House floor. Sometimes “restrictive rules” protected bipartisan deals hatched in committee; other times, they immunized party priorities from challenges on the floor. Judging from the number of Hastert Rule violations charted below (as identified by the New York Times’ congressional votes wiz in my twitter feed), it was extremely rare (even before Hastert became speaker in 1999) for the majority party to be rolled on a final passage vote. (To put the number of violations into perspective, there are roughly under 200 final passage votes in most recent congresses, meaning that majority rolls typically constitute less than five percent of final passage votes.) In other words, the Hastert Rule reflects a decades-long pattern in the House of more aggressive Democratic and Republican majority party leaders (denoted by the blue and red bars below) willing to exploit chamber rules on behalf of cohesive majorities.

A brief data digression … Cox and McCubbins’ count of majority party rolls on final passage differs in a few congresses from the NYT’s count. I suspect this stems from the NYT’s more generous reading of “final passage” to include final House votes to concur on Senate amendments, from the NYT’s inclusion of a supermajority suspension vote, and so on. Regardless, the N’s are very small here. And that’s the point. Still, these data might underestimate leaders’ fealty to Hastert’s rule, since the measure by necessity excludes measures pulled off the floor by leaders eager to avoid party-splitting votes. (For a different critique of roll rates, see Krehbiel’s work here.)

Second, the Hastert Rule violation on the Hurricane Sandy bill was typical of many majority party rolls: A good portion of majority rolls occur on “must-pass” bills. Some of these are must-pass because they are mandated by previous legislative decisions. For example, a majority of the Republican majority in 1997 was rolled on a motion to reinstate funding for international family planning groups, a vote that was mandated by a previous year’s spending bill. Other rolls, such as last night’s Sandy disaster relief vote, occur on appropriations bills. (Even if House Republicans threaten to shut down the government this year, I’m still counting these as “must pass” bills!) The remaining rolls tend to occur on salient, popular issues for which the majority party might pay a reputational cost for opposing. Majority party rolls on campaign finance in 2002 and on stem cell research in 2005 come to mind. In other words, more seems to be at stake in these votes than the policy commitments of the majority party’s rank and file. Instead, leaders seek to avoid blame for blocking what amount to must-pass measures. Leaders’ perceived need to attend to their party’s brand name might compel them to facilitate votes in these cases, even at the cost of violating Hastert’s rule. That motivation seemed to undergird Boehner’s 11th hour move to allow a vote on the Senate-passed fiscal cliff deal. Such calculations also likely shaped Boehner’s about-face on the Sandy relief bill after Governor Chris Christie gave GOP leaders a tongue-lashing for killing the bill at the close of the last Congress.

Finally, keep in mind that on the fiscal cliff and Sandy rolls, the leadership brought the bills to the floor under restrictive rules endorsed by a majority of the majority party. The party was not rolled on the pivotal procedural vote. As Frances Lee and David Karol observed here, nearly every Republican voted in favor of bringing the Senate-passed fiscal cliff deal up for a vote. And nearly every GOP voted to bring the Sandy spending bill to the floor. This certainly suggests that despite the Hastert Rule violation, Speaker Boehner has not lost control of his conference. Rank and file members seem to understand that on a narrow set of bills, their party leaders’ hands are tied: Killing a bill is understood to be unacceptable, and so instead legislators make the best of a bad hand by casting votes against the bill—knowing it will pass. The trillion dollar (platinum, of course) question is what other bills (at the 11th hour) might be deemed “must-pass” by the GOP in the 113th Congress. The bill to raise the debt ceiling? A move to avoid the sequester? The next omnibus spending bill? Possibly all three. And will other measures gain must-pass status as well, perhaps fueled by strong public sentiment even from some GOP quarters? Immigration reform and scaled-back gun control are potential candidates. How Boehner manages conflict between the party’s brand name and his rank and file’s policy priorities will shape the fate of the Hastert Rule (and Boehner speakership’s that lies in the balance).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Oh 113th Congress Hastert Rule, We Hardly Knew Ye!

January 17, 2013