The report available for download is a forthcoming publication of the Journal of Economic Perspectives in the summer 2024 issue.

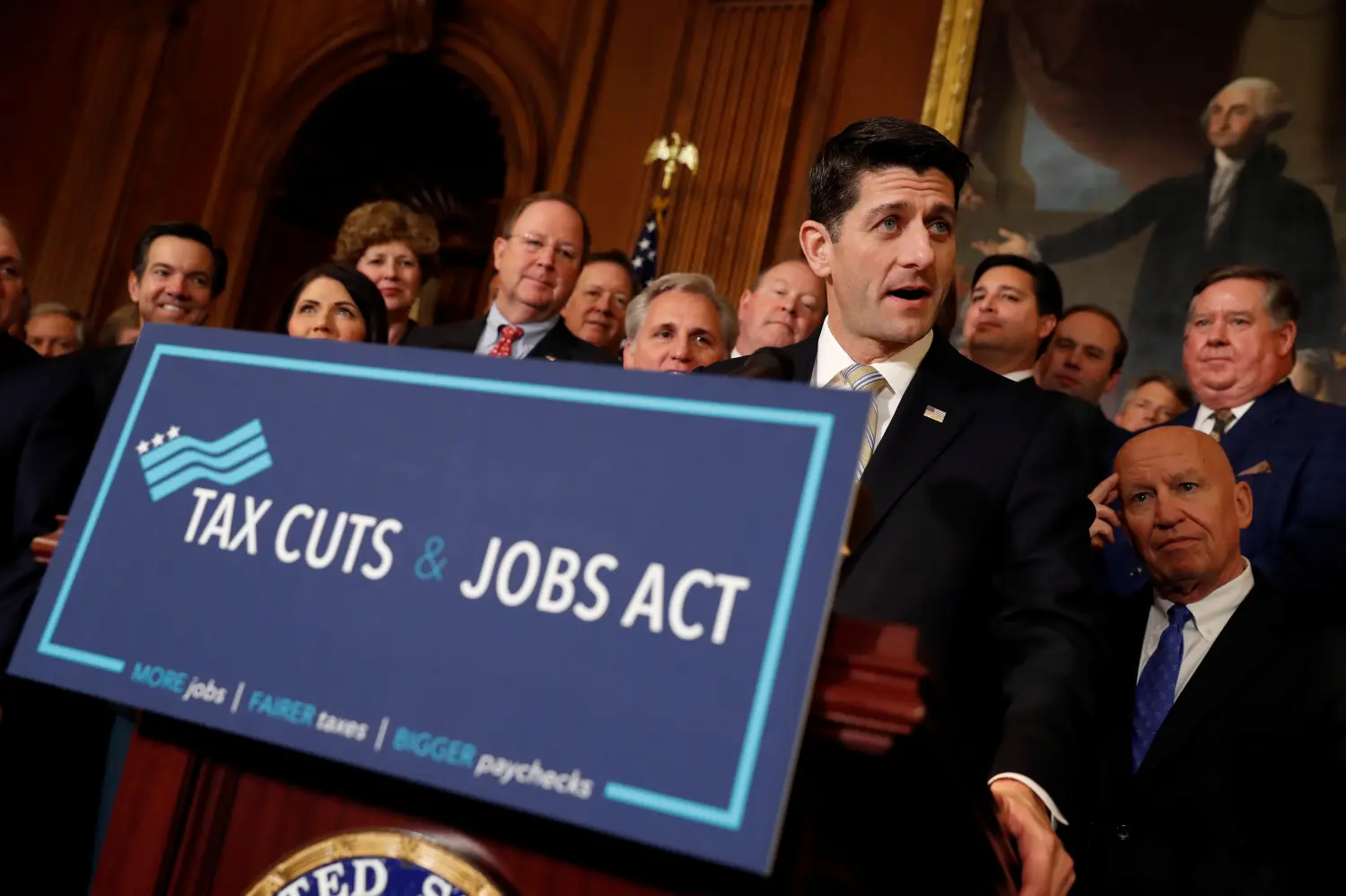

Many parts of former President Trump’s signature tax cuts will expire in 2025. This leaves limited time for policymakers to decide what to keep, what to let lapse, and how to deal with the other provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). Whatever course of action they take will affect the federal deficit and how millions of households and businesses do their taxes.

To make those decisions, Congress needs to look past party lines and talking points to see the law’s actual impact. In a new paper, Jeff Hoopes (University of North Carolina), Kyle Pomerleau (American Enterprise Institute), and I did just that.

The TCJA introduced sweeping changes to individual and corporate taxation, cutting individual income tax rates, increasing the standard deduction and Child Tax Credit, slashing the corporate tax rate and the tax rate for certain unincorporated businesses, and other changes.

Here’s my take. Several effects of the law are clear. First, the good news. It simplified taxes for many households by reducing their dependence on itemized deductions and their use of the alternative minimum tax (AMT), although these gains were offset to some extent by more complicated taxes for businesses.

The bad news is that it was expensive: The TCJA will have raised federal deficits and debt by more than $2 trillion over its first 10 years according to the Congressional Budget Office. Forget the idea that the tax cut will pay for itself—that is nonsense.

More bad news: The TCJA exacerbated the already massive differences in the distribution of income. It made the rich richer and barely helped the poor. Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center analysis shows that households in the lowest 20% of income distribution gained an average of about $60 per year. Annual tax cuts for the top 1% averaged over $50,000.

These are justifiable costs, say TCJA advocates, who believe the law spurred economic growth. But there does not appear to have been a growth effect. Patterns in aggregate economic data for 2018 and 2019 tell a fairly simple story: The basic underlying path of the economy—in terms of GDP, investment, and wages—was essentially unchanged after TCJA relative to before TCJA.

For example, a boom in investment never materialized. Investment was about the same share of GDP in 2019 as it was in 2015. Investment in intellectual property continued to grow at about the same rate that it had before the tax cut. Investment in equipment and structures, both of which received big tax cuts through the TCJA, essentially stagnated as a share of GDP.

U.S. investment performance compared to other countries was lackluster, too. Before TCJA, our investment-GDP ratio grew at the second fastest rate in the Group of Seven (G7). After TCJA? The fourth fastest. Lagging behind Europe is not the best look for the “biggest business tax cut in history.”

In particular, the historic cut in the corporate tax rate, down to 21% from 35%, was much less of an investment incentive than many TCJA advocates expected. The reduction mainly provides a windfall gain to investments made in the past—an inefficient way to stimulate new investment.

If TCJA provisions didn’t contribute to growth, their absence is unlikely to hurt growth.

Hopefully in 2025, rather than continued partisan politicking, policymakers will seriously study the actual effects of TCJA policies when considering whether to extend them or let them lapse. Extending the expiring provisions would cost more than $4 trillion over the next decade according to CBO and would be extremely regressive. If the provisions expire, the economy is unlikely to fall into a tailspin. If TCJA provisions didn’t contribute to growth, their absence is unlikely to hurt growth, and it would help reduce the deficit and make the distribution of after-tax income more equal.

How to deal with TCJA is part of a larger discussion: How will the U.S. generate sufficient revenue to cover its expenses? Budgetary challenges are only getting worse, given slowly growing revenues and looming shortfalls in the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. If policymakers limit their debate in 2025 to the expiring TCJA provisions, they will miss a huge opportunity to reform the tax system and reduce fiscal deficits. Congress has many options, and many better ones, than simply extending TCJA.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Gale gratefully acknowledges financial support for the report from Arnold Ventures and the California Community Foundation. The authors thank Jonathan Parker, Timothy Taylor, and Heidi Williams for helpful comments and Oliver Hall, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, and Sam Thorpe for outstanding research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports, published online. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).