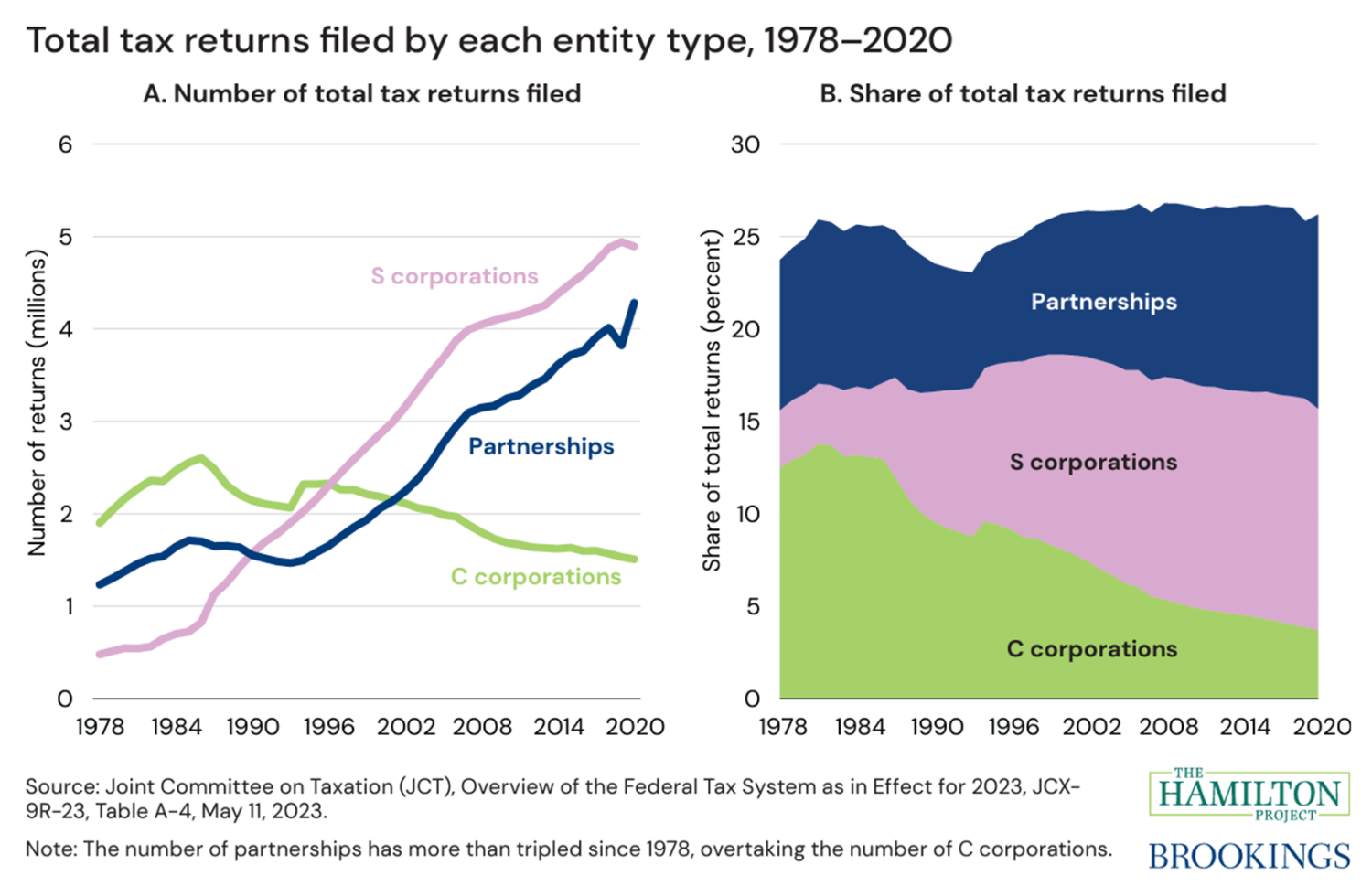

Partnership tax reform should be a key part of the current and upcoming tax policy debate, with large parts of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) set to expire at the end of 2025. Partnerships represent almost 30 percent of all business income in the United States, now outnumbering C corporations. For federal tax purposes, partners are taxed directly on their share of the partnership’s income and activities. The partnership itself is not a separate taxable entity and partners are not subject to two layers of tax that other businesses like C corporations face. Yet the tax treatment of partnerships—which can offer tax advantages over other business structures—has not attracted attention proportionate to their growing prevalence. Partnership tax rules have not been the subject of broad reform since their enactment in 1954. This is a source of substantial revenue loss. A 2012 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimated that if tax rules for C corporations had applied to partnerships and S corporations in 2007, total federal revenues would have been about $76 billion higher (or $100 billion in 2021 dollars). In 2021, comprehensive partnership tax reform proposals were publicly estimated to raise at least $172 billion over 10 years (and may raise significantly more). In this policy proposal, Miles Johnson, Sophia Yan, Chye-Ching Huang, and Grace Henley (The Tax Law Center at NYU Law) examine the current structure of partnership taxation and present a selection of reform proposals that would modernize partnership taxation, focusing on options most relevant to the 2025 tax policy debate.

The challenge

Complexity and flexibility: Some 85 percent of partnership structures are simple—a single partnership owned directly by individuals, like a medical practice jointly owned by two doctors. But a small number of large and complex partnerships, typically in finance and real estate, account for the vast majority of partnership income and assets. From 2002 to 2019, the number of partnerships that qualify as “large” (i.e., $100 million or more in assets and 100 or more total partners) and “complex” (i.e., 20 or more tiers of ownership) increased from 36 to more than 6,000. Large partnerships often involve complicated webs of ownership and tax returns that are difficult to decipher. While partnership tax rules can be flexible enough to accommodate the taxation of many modern businesses, they can also facilitate wildly complex structures that are engineered to avoid taxes or even facilitate illegal tax evasion.

Revenue loss: The preferential nature of partnership taxation results in significant reductions in federal revenues—a particularly important issue when the nation faces long-term fiscal and federal investment deficits. The main sources of revenue loss include preferential taxation relative to C corporations, avoidance of taxes on capital and labor income, and noncompliance. For example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates that partnerships, along with S corporations and some trusts and estates, contribute about $40 billion annually to the “tax gap” (taxes owed under current law but not paid).

Opacity: Despite their growing role in the economy and the tax system, it is difficult to obtain some of the most basic information about partnerships, such as the number and identity of partnership owners. Research with IRS data found that more than 20 percent of partnership income could not be readily traced to known types of entities or individuals.

Weaknesses in the laws governing partnership tax administration contribute to difficulties fully understanding partnerships and how they are taxed. This includes a lack of third-party reporting requirements that would allow the IRS to verify partnership income, deficiencies in ownership and structure reporting, and the complexity of partnership tax returns.

The proposal

The proposal offers a specific selection of suggested legislative and regulatory reforms ranging from targeted fixes to broader reforms. Representative examples are highlighted below.

Reporting and administration: Expanding electronic filing for partnership returns, improving existing partnership tax and ownership reporting, and maintaining and improving IRS compliance funding all would increase information about partnership income, assets, and noncompliance. This would support voluntary compliance and ensure that IRS efforts are more efficient and better targeted.

Clean ups and similar fixes: These include simple clean-ups and clarifications to ensure current partnership rules operate as intended and expected. For example, the proposal includes a legislative clean-up of section 707(a)(2)(b), addressing disguised sales of partnership interests. As with assets like stocks and bonds, when a taxpayer sells its stake in a partnership, the taxpayer should pay tax on any gains. However, a taxpayer can try to achieve more favorable tax treatment by “disguising” what is economically a sale as a different, more tax-favored transaction (namely, a liquidation of its interest). The best reading of the statute is that it prevents this result, but the statute should be clarified to foreclose any doubt.

Targeted reforms: These include broader recommendations that would target specific abuses or gaps in partnership tax law. One such recommendation is supplementing related party basis shifting regulation with additional legislation. A large business that controls several entities (including at least one partnership) can trade assets among them to generate tax savings, taking advantage of specific quirks of partnership tax law. This generates tax savings for the owner even though no real economic transaction has taken place: The assets remain under the same ownership before and after the transaction. The U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS have announced welcome guidance to address certain basis shifting transactions, and legislation could support and simplify this approach.

Broader and more complex reforms: These recommendations encompass larger reforms with a bigger and more complex impact on existing partnership rules. One example is updating, modernizing, and clarifying section 704(b) allocation rules. Partnerships pass through their income and deductions to their partners. Section 704(b), which governs the allocations of income and deductions to partners, is therefore at the core of partnership tax. The current rules are designed to permit allocations so long as they are consistent with actual economic results. However, these rules have features that permit inappropriate tax planning, including allocations that are not in fact consistent with economics. Those specific features should be fixed, and other updates should be studied and pursued that would better reflect appropriate sharing and current market practices.

Fundamental reforms: The proposal also discusses options for more fundamental reforms and explores their benefits and challenges. These include 1) limiting favorable Subchapter K treatment to a narrower range of businesses or entities, and taxing others under a different regime (e.g., as C corporations) and 2) creating a “simplified” and less flexible pass-through regime into which small partnerships can elect. A significant challenge in both approaches is setting and measuring the threshold that determines which entities would receive which treatment, which has material tax consequences for the entity and its owners.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are extraordinarily grateful to participants in a June 2024 author’s conference organized by The Hamilton Project for their generative feedback on an earlier draft, as well as to numerous additional academics, practitioners, and experts for their thoughtful feedback. Noadia Steinmetz-Silber of The Hamilton Project provided valuable research assistance. Thanks also to the rest of the Hamilton Project team for their thoughtful guidance on the proposal.

Commentary

Modernizing partnership taxation

September 25, 2024

Key takeaways: