With 2023 winding down, we asked six Brookings experts to take a moment to look back on some of the biggest economic policy developments of 2023 and the ways they expect them to evolve in 2024. Explore their reflections on fiscal policy, the social safety net, climate economics, and more below.

Chloe East

Visiting Fellow, The Hamilton ProjectOn some dimensions, the U.S. labor market appears to have mostly recovered from the COVID-19 shock and to be stronger than before. By early 2022, the unemployment rate fell back to the very low levels seen right before the pandemic, and it has remained relatively stable throughout 2023 despite slowing job growth and rising interest rates. Median real weekly earnings among workers are now slightly higher than they were at the end of 2019. However, these encouraging points do not paint the full picture. The percent of the population out of the labor force is still much higher than before the pandemic. And half a million workers went on strike in 2023 demanding higher wages and improved working conditions. All of this comes against the backdrop of high, albeit falling, rates of inflation over 2023. The question remains of how workers have fared in the labor market overall.

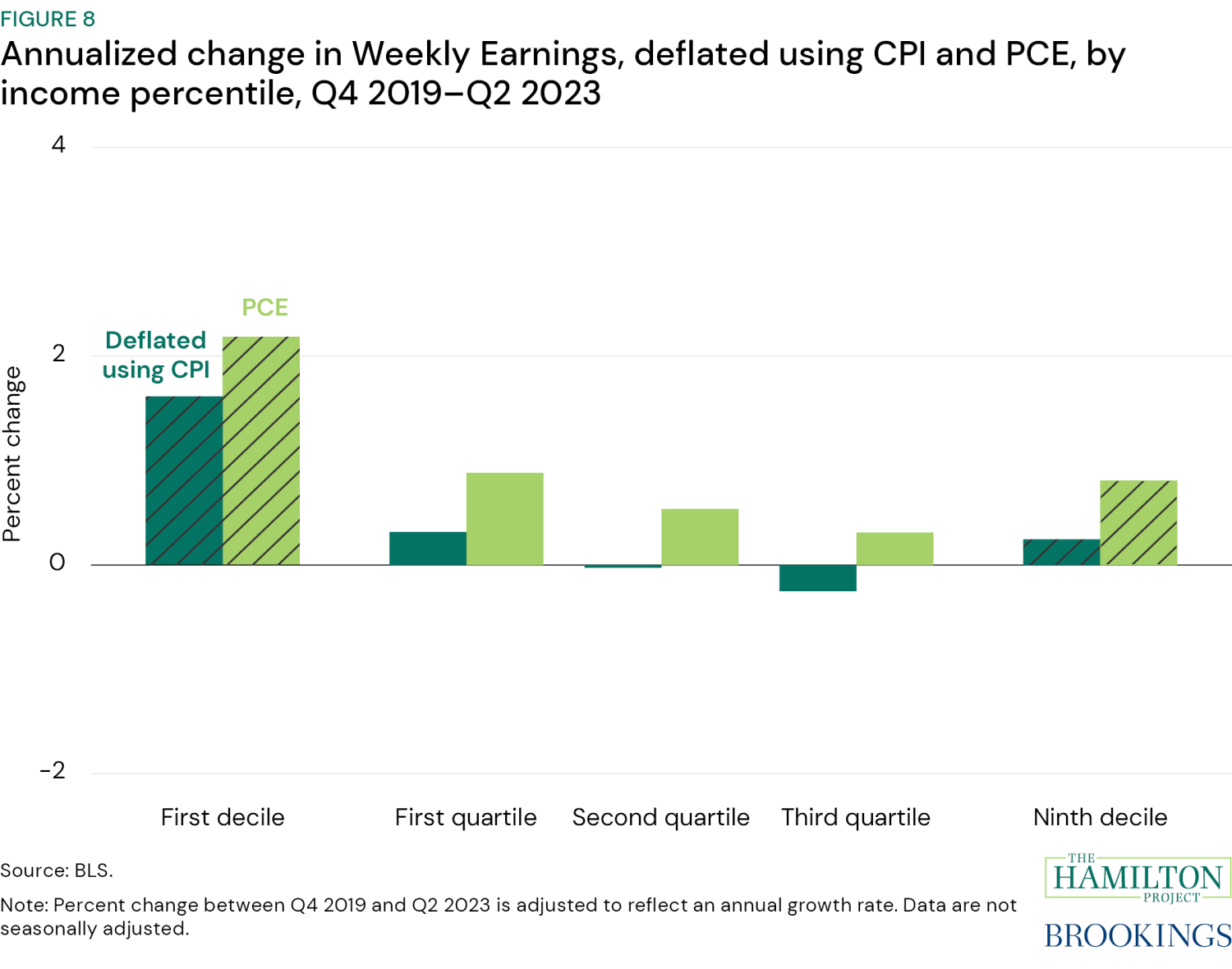

In a Hamilton Project piece with Wendy Edelberg and Noadia Steinmetz-Silber, we reviewed evidence about how workers’ real pay has changed over the last few years in the U.S. We considered multiple measures of pay for different types of workers and used different measures of inflation, in comparison to various reference periods. Overall, we see some reasons for optimism. All pay measures that we examine have increased slightly relative to the end of 2022 and the end of 2019. Comparing to longer-run trends, most pay measures, adjusted for inflation using PCE, are recently showing gains that are somewhat above the levels predicted by historical trends. And the measures generally show that workers in lower-wage occupations and industries and those with lower earnings have seen larger gains since 2019.

However, not all of the news about real pay is as positive. First, even with recent gains, pay at the bottom of the distribution is still quite low and puts many households at or below the poverty line. Additionally, this trend of rising real pay at the bottom of the distribution appears to be weakening in recent quarters. Second, workers in the middle of the distribution saw more mixed changes in pay than those at the bottom or the top—some metrics show small gains and some show small losses for those in the middle. And finally, when pay is adjusted using CPI instead of PCE, which reflects the prices that are most salient to the average consumer, pay changes are weaker and, in some cases, were even negative.

Going forward I will be looking out for several key indicators of workers’ well-being. First, it is important to continue to pay attention to how real pay is changing, especially for different types of workers rather than just in the aggregate or for the average worker. Second, it will be crucial to focus on metrics of working conditions and worker compensation that are less traditionally studied, such as schedule reliability and access to benefits, particularly as alternative work arrangements like contractor and gig work become more common.

Ben Harris

Vice President and Director, Economic Studies and Director, Retirement Security ProjectRetirement security remains an important economic issue. In 2023, the most notable “development” in this space, perhaps ironically, was no progress in terms of putting Social Security and Medicare on a sustainable fiscal path. While the Trustees of the Social Security Trust Fund estimated that the exhaustion date was moved up by one year to 2033, Congress made little to no progress on advancing a reform plan.

The continued recovery from the pandemic was also notable for retirement security, especially in terms of older worker participation in the labor market. The participation rate of older workers without a disability plummeted 3 percentage points in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, but over the course of 2023 the labor market recovered about one-third of this loss. Further participation gains are significant as they signal an ability of older workers to gradually transition into retirement and improve their financial well-being in later years.

On the policy front, the most impactful development of 2023 was the implementation of the SECURE 2.0 Act—a set of incremental policy reforms designed to improve the retirement security outlook. Many of the provisions are phased in over time, such as the reform of a matching credit for contributions to retirement accounts by low- and middle-income households. But many of the provisions took effect in 2023, such as an initial increase in age at which savers must take required minimum distributions from retirement accounts.

A second important development was the onset of plans to curb increases in prescription drug pricing. For example, a few weeks ago the Department of Health and Human Services announced several dozen drugs with sufficiently rapid price increases to qualify for the Rebate Rule—which would effectively tax prescription drug companies for boosting prices too quickly.

A third important development was the release of a draft rule by the Department of Labor to expand protections for consumers receiving financial advice, including when purchasing fixed index annuities (annuities with a payout that typically depends on a stock market index). This “Retirement Rule” can potentially shake up the market for financial advice, with an aspiration that lifetime savings are directed to the best use for savers when they retire or rollover their savings.

With 2024 featuring a presidential election and a divided Congress, there appears to be limited opportunity for major reform—changes to Social Security and Medicare will almost certainly be omitted from the legislative docket. But important developments will occur under the radar, namely those related to already passed provisions on prescription drugs and the implementation of the Secure 2.0 Act. While these reforms are largely incremental in nature, they will cumulatively create additional stability for Americans’ retirements and serve as a foundation for enacting future retirement protections.

Sanjay Patnaik

Director, Center on Regulation and MarketsRelated to climate change, one of the most important developments in the domestic policy space was the implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S.’ first major legislation to address climate change. A major issue the Center on Regulation and Markets has focused on is permitting reform, a topic that is often neglected but without which the expected climate benefits of the IRA are unlikely to materialize. In addition to regularly engaging with a wide range of stakeholders on this topic, we published an article on how permitting could be reformed in the U.S. to make it more streamlined and allow necessary infrastructure to be built faster.

Another essential aspect of the IRA we focused on was the potential impact of the IRA on U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, which was modeled and estimated by several research groups ahead of the passage of the IRA. However, the U.S. currently does not have an independent government office that could estimate the carbon impact of certain legislation in a non-partisan and independent manner. We therefore launched a Brookings task force on creating the blueprint for a federal Office of Carbon Scoring in the U.S., “to provide the institutional, analytical, and policy foundation for establishing a federal Office of Carbon Scoring (OCS) that would analyze the potential impact of proposed legislation on greenhouse gas emissions and other relevant climate metrics.” We also published a commentary on how carbon scoring could help Congress make real progress on climate change, further outlining our idea of carbon scoring in greater detail.

Another timely topic we focused on in the climate space was the behavior of firms in carbon markets, which are becoming increasingly important around the world, not only though mandatory carbon pricing regulations but also through voluntary carbon markets. On this topic, I published a working paper on how carbon permit markets can lead firms to capture surplus rents by drawing on empirical evidence from the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS). Similarly, we advanced our work on climate risk management, which is increasingly becoming important for governments, corporations, and consumers. In our most recent working paper on this topic, we propose a new framework for how firms can manage their climate risk exposure.

One important trend to watch out for in 2024 relates to a potential carbon border tariff in the U.S., as several bills related to a carbon tax in the U.S. were released recently, undoubtedly in response to the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Three of the bills were bipartisan, which is a strong indication that there is potential room for the U.S. to institute some kind of carbon border fee, which would align it more closely with the EU.

Louise Sheiner

Policy Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary PolicyIn 2023, investors began worrying about federal budget deficits again. Interest rates on U.S. Treasuries moved up sharply, despite the fact that budget analysts have been warning about the challenges of debt sustainability for decades. Why all the renewed attention to the deficit? A few possible reasons include:

- The budget deficit increased sharply in fiscal year 2023. After adjusting for the announcement and subsequent cancellation of Biden’s student loan forgiveness program, the deficit doubled from about $1 trillion in FY 2022 to $2 trillion in FY 2023.

- The standoff over the debt limit, the threat of a government shutdown, and the downgrading of U.S. debt by Fitch all increased concern about political dysfunction in Washington—perhaps suggesting to investors that it would take longer than they had anticipated for the government to start addressing the long-run budget challenges.

- The increase in interest rates—perhaps caused by renewed deficit worries, perhaps not—also led to increased concern over the deficit. The higher are interest rates, the faster the rise in the debt for any given set of tax and spending policies.

But in my view, nothing fundamental changed in 2023. A detailed breakdown shows that the jump in the deficit in 2023 reflected temporary and/or one-time factors that don’t imply that future deficits will be higher. And even before the recent political events, it didn’t seem likely that Congress was going to address our long-term fiscal challenges any time soon.

Since nothing fundamental changed in 2023, it is hard to understand the recent increase in rates: Were markets just not paying attention to fiscal issues until recently? Did they misinterpret the jump in the FY 2023 deficit as signaling larger deficits in the future? Or perhaps the recent increase isn’t about fiscal issues—perhaps it reflects changes in expectations about Federal Reserve policy or even increased productivity growth because of artificial intelligence. A surge in productivity growth, should it materialize, could greatly improve our fiscal outlook, offsetting the effects of higher interest rates.

Recent data suggest that at least part of the surge in rates was temporary: After hitting a post-2007 peak in October 2023, interest rates on Treasuries have been drifting down. Still, the rate on 10-year inflation-protected Treasuries on December 19, 2023 was about 1½ percentage points higher than its average in 2019. Will rates continue to decline, or will they settle at this higher level? Will the focus on the deficit continue—or will it fade away? These are issues I will be watching in 2024.

I’ve been watching the evolution of the U.S. safety net retreat back to a “new normal” after massive expansion in the COVID era. Food assistance—SNAP (the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program)—temporarily increased benefits and added an emergency allotment, changes that had phased out by early 2023. In 2021, the temporary expansion of the federal Child Tax Credit (CTC) made an enormous difference, especially for lower-income families. We saw child poverty fall by almost half for that one year.

Despite the end of SNAP emergency allotments and the expanded CTC, we are not quite returning to the pre-COVID safety net. In 2021, the federal government updated the Thrifty Food Plan, a change that was already in the works and boosted the amount of food assistance SNAP provides. Even with the end of the temporary measures, food assistance will remain above 2019 levels.

And states were also making changes to their safety net supports. The safety net is actually not one safety net, but at least 51 safety nets comprised of a patchwork of federal, state, and local programs. Over the last decade, many states were creating or expanding state Earned Income Tax Credits. Many states increased their TANF cash assistance programs before and during COVID, whereas others let the value of TANF benefits continue to erode. Even though the federal government helps equalize support across states, striking differences remain.

Looking ahead, there are a few safety net issues that will be important in the coming year or two:

First, there will be continued discussion about the CTC. There was momentum around getting the 2021 expansions made permanent, an effort which ultimately failed. But the more modest current version, which was part of the 2017 Trump tax law, will expire in 2025. There are debates about how much if any should go to non-earners, and how high up in the income distribution the credit should go. My colleagues proposed one compromise version.

Second, there is a bipartisan support for long-overdue reforms to the Supplemental Security Income program for low-income Americans with disabilities—raising the asset limits. Right now if single individuals have more than $2,000 in the bank they can’t qualify for benefits, which is a strong disincentive to save. There’s an opportunity to fix that in 2024.

Third, it will be interesting to see how states continue to use their income tax systems to help support children and families. When the expanded federal CTC ended at the end of 2021, some states opted to build on that success by developing their own CTCs. As states continue to experiment, it could widen the significant differences across states in safety net support.

Marta Wosińska

Senior Fellow, Center on Health PolicyFor over two decades, drug shortages have plagued various parts of the healthcare system, mostly in the hospital setting—only occasionally hitting the national headlines. 2023 was yet another year with over 100 unique drugs on FDA’s drug shortage list. The persistent nature of shortages may have gone unnoticed yet again were it not for some high-profile shortages, the most prominent and unnerving of which have been shortages of inexpensive, standard-of-care cancer treatments.

Drug shortages are primarily driven by economic forces. Most shortages occur with generic drugs where the fierce price competition that drives spending down for consumers and payers also turns up the dial on cost cutting. Companies making generic drugs have little incentive to invest in quality oversight and in buffering their supply chains, which raises the risk of manufacturing disruptions that then turn into shortages. This dynamic is particularly consequential for the hard-to-manufacture sterile injectable drugs. Companies also have a strong incentive to purchase cheaper inputs and off-shore production to lower cost environments, which can expose our drug supply chains to geopolitical risks.

With cancer shortages in the headlines, several Congressional committees held hearings on the issue including HSGAC, House Energy & Commerce and Senate Finance. Proposals for administrative and legislative actions abound, but there continues to be lack of appreciation for what actions will address root causes, what actions might help but might also be potentially wasteful, and what actions might frankly make things worse. The inability of policymakers to sort through the various ideas is particularly concerning because addressing shortages will require greater government spending, for which there is currently limited appetite.

To inform executive branch actions and legislation, colleagues and I have put forward a number of analyses coupled with policy recommendations, which I had the opportunity to highlight recently in my testimony with the Senate Finance committee. In a June report, Richard Frank and I proposed what the Medicare program and FDA can do to prevent and mitigate shortages of generic sterile injectable drugs caused by manufacturing quality lapses. To address the risk of future shortages due to geopolitical and climate change risks, colleagues and I developed a framework for how the federal government should assess which supply chains are most vulnerable to disruption—a key step in prioritizing government support. Other work includes recommendations on CMS’s proposal for building buffer hospital inventories and for implementing the IRA drug shortage provisions. Most recently, I had the opportunity to reiterate many of these recommendations in my testimony with the Senate Finance committee.

There is currently motivation in Congress to address drug shortages, but this may subside once the cancer drug shortages disappear from national news. Our Brookings team will continue to be actively engaged in educating policymakers and stakeholders on the issue, working to ensure that the suffering so many patients endured this year from drug shortages will cease to be the norm.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Major economic developments of 2023 and how they’ll evolve in 2024

December 21, 2023