For the last decade, district-embedded school leadership preparation programs have been on the rise; however, little research has been done about what sets these programs and their results apart from more common routes into educational leadership. Noting shortcomings in traditional school leadership Masters degree programs and alternative licensure programs such as New Leaders, some school districts have looked inward to produce the school leaders they need. These motivated school districts are now selecting, training, placing, supporting, and evaluating aspiring school leaders utilizing their own internal talent, their own internal leadership frameworks, and their own internal evaluation rubrics.

After a 21-month immersive evaluation of one such program established by the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) for my doctoral dissertation, I will highlight some of the key takeaways from this new and growing trend in school leadership development.

In January 2013, DCPS launched the Mary Jane Patterson Fellowship, a 30-month program for high-performing DCPS talent with school leadership potential. Cohorts of 10-12 fellows embark upon a learning journey comprised of five phases in which aspiring school leaders participate in lengthy and frequent learning sessions taught by DCPS principal experts and Central Office leaders, a one-year principal residency under the mentorship of a DCPS mentor principal, and extensive opportunities for fellows to not only learn from the best internal talent at DCPS but also to demonstrate to DCPS leaders that they are ready for the principalship. Survey data from a 2015 program evaluation noted the Patterson Fellowship is widely regarded as a highly effective principal development program both by participants and Central Office leaders, with 100 percent of Central Office leader participants lauding its process and results and 100 percent of fellow participants characterizing it as an extremely positive experience.

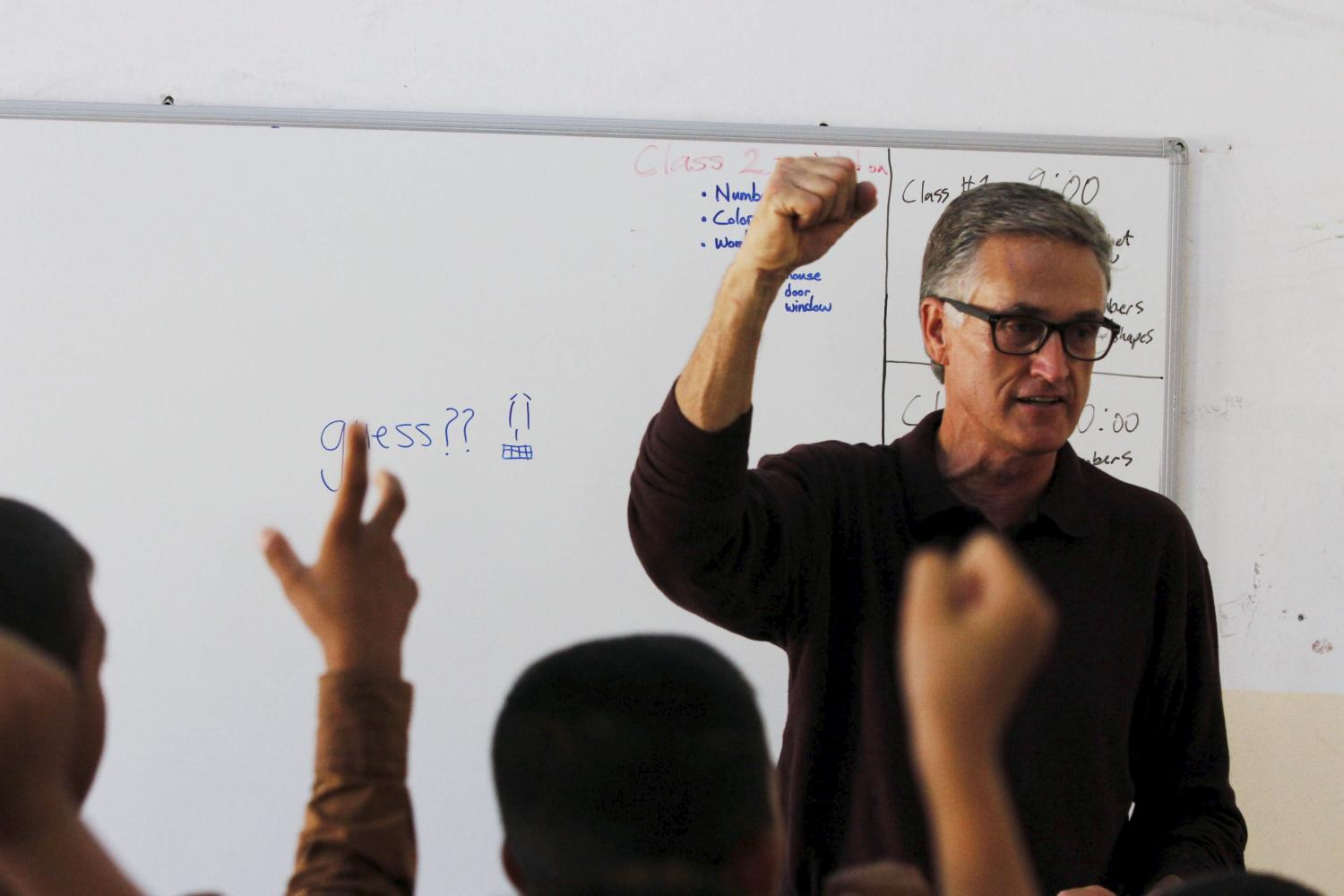

Throughout this study, I asked fellows to reflect upon programmatic activities within the Fellowship that were most beneficial in their first year as principals. Fellows overwhelmingly cited the following programmatic features: cohort membership, access to the Central Office leadership, and the residency internship experience in which principals work closely with an experienced DCPS mentor principal as having the most impact on their school leadership abilities in their first year. Notably absent were references to learning sessions, curricular content, and other “classroom-based” activities designed to improve individuals’ discrete leadership practices.

Through initial data collection and analysis, it became apparent that these three programmatic features—the cohort, Central Office access, and experience leading within the DCPS context through the residency—are beneficial to learning because of their impact on the fellows’ ability to cultivate social capital. Fellows’ unique access to aspects of the Fellowship that could be said to contribute to the development of social capital within DCPS is frequently cited as the main habitus that sets fellows apart from principal peers trained outside the district.

The cultivation of social capital within the Fellowship has led to improved self-awareness, trusting relationships with superiors, openness to feedback, and ease in navigating the complexities of DCPS once in the role of principal. Fellows in their first year of the principalship stated they felt comfortable asking their peers and superiors for help, had a strong support network within their cohort, felt DCPS believed in them and their abilities, and believed Central Office leaders were their advocates feelings far too few principals authentically experience in their first years on the job. In short, district embedded training in DCPS made one of the loneliest professions far less lonely through the accumulation of social capital.

District-embedded programs originally were developed in response to challenges such as an inability to attract qualified leaders with training reflective of district culture and priorities, as well as the perceived inadequacy of both traditional academic leadership development and alternative certification programs. However, the ability of district-grown principal pipeline programs to inspire an expectation that its graduates will be successful, long-term district leaders is attributable to something more than the content of the training itself. Through a close, embedded look at the Patterson Fellowship, I have attempted to identify and articulate exactly what that “something” is and to suggest how it can be replicated. Social capital, cultivated through relationship building among cohorts of peers, district leaders, and mentor principals, seems to be the X-factor that sets district-embedded programs apart from training programs outside the district.

“Social capital, cultivated through relationship building among cohorts of peers, district leaders, and mentor principals, seems to be the X-factor that sets district-embedded programs apart from training programs outside the district.”

Districts evaluating their own preparation programs, as well as those considering the establishment of their own pipeline programs, should recognize the value of social capital to the future success of program graduates. They should also ensure that their program’s structure includes the elements the Patterson Fellowship has linked to social capital accumulation. Graduates of district-embedded principal training programs enter school leadership with greater ease in navigating the complexities of school leadership, a group of trusted peers to call on for help, as well as a network of district leaders and expert principals to reach out to for support and advice. School leaders with greater social capital currency feel more connected and are more effective; therefore, a focus on social capital cultivation within leadership preparation programs would be beneficial for aspiring leaders and the districts they serve.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).