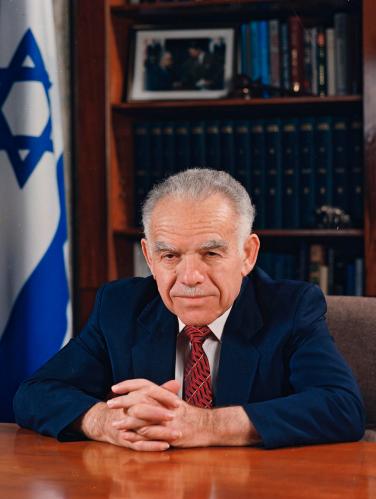

Shimon Peres was pillar of Israel’s national security leadership and subsequently became an ardent peacemaker. Perhaps most important, writes Itamar Rabinovich, he was an Israeli leader who had a vision and a message. This piece originally appeared on Project Syndicate.

In 2006, a year before Shimon Peres was elected as Israel’s president, Michael Bar-Zohar published the Hebrew edition of his Peres biography. It was aptly titled Like a Phoenix: by then, Peres had been active in Israeli politics and public life for more than 60 years.

Peres’s career had its ups and downs. He reached lofty heights and suffered humiliating failures—and went through several incarnations. A pillar of Israel’s national security leadership, he subsequently became an ardent peacemaker, always maintaining a love-hate relationship with an Israeli public that consistently declined to elect him prime minister but admired him when he did not have or seek real power.

Undeterred by adversity, Peres kept pushing forward, driven by ambition and a sense of mission, and aided by his talents and creativity. He was a self-taught man, a voracious reader, and a prolific writer, a man moved and inspired every few years by a new idea: nanoscience, the human brain, Middle Eastern economic development.

Undeterred by adversity, Peres kept pushing forward.

He was also a visionary and sly politician, who never fully shook off his East European origins. When his quest for power and participation in policymaking ended in 2007, he reached the pinnacle of his public career, serving as President until 2014. He rehabilitated the institution after succeeding an unworthy predecessor and became popular at home and admired abroad as an informal global Elder on the international stage, a sought-after speaker in international fora, and a symbol of a peace-seeking Israel, in sharp contrast to its pugnacious prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

Peres’s rich and complex political career passed through five main phases. He began as an activist in the Labor Party and its youth movement in the early 1940s. By 1946, he was considered senior enough to be sent to Europe as part of the pre-state delegation to the first post-war Zionist Congress. He then began to work closely with Israel’s leading founder, David Ben-Gurion, at the Ministry of Defense, mostly in procurement, during Israel’s Independence War, eventually rising to become the ministry’s director-general.

In that capacity, Peres became the architect of the young state’s defense doctrine. Running a sort of parallel foreign ministry, his main achievement was the creation of a close alliance and strong security cooperation—including with respect to nuclear technology—with France.

In 1959, Peres moved to full-time politics, supporting Ben-Gurion in his conflict with Labor’s old guard. Later, he was elected to the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, and became Deputy Minister of Defense and subsequently a full member of the cabinet.

His career entered a new phase in 1974, when Prime Minister Golda Meir was forced to resign after the October 1973 debacle, in which Anwar Sadat’s Egyptian forces successfully crossed the Suez Canal. Peres presented his candidacy, but narrowly lost to Yitzhak Rabin. As compensation, Rabin gave Peres the position of defense minister in his government. Nonetheless, their contest in 1974 marked the start of 21 years of fierce rivalry, mitigated by cooperation.

Twice, in 1977, after Rabin was forced to resign, and in 1995-1996, after Rabin was assassinated, Peres succeeded his rival. He was also prime minister (a very good one) in a national unity government in 1984-1986; but, despite trying for nearly 30 years, he never won his own mandate from Israeli voters for the post he coveted the most.

In 1979, Peres transformed himself into the leader of Israel’s peace camp, focusing his efforts in the 1980s on Jordan. But, though he came tantalizingly close to a peace deal in 1987, when he signed the London Agreement with King Hussein, the agreement was stillborn. In 1992, the Labor Party’s rank and file concluded that Peres could not win an election, and that only a centrist like Rabin stood a chance.

Rabin won and returned, after 15 years, to the premiership. This time, he kept the defense portfolio for himself and gave Peres the foreign ministry. Rabin was determined to manage the peace process and assigned to Peres a marginal role. But Peres was offered by Rabin’s deputy an opportunity to champion a track two negotiation with the PLO in Oslo, and, with Rabin’s consent, took charge of the talks, bringing them to a successful conclusion in August 1993.

Here was the prime example of competition and collaboration that typified the Rabin-Peres relationship. It took Peres’s boldness and creativity to conclude the Oslo Accords; but without Rabin’s credibility and stature as a military man and security hawk, the Israeli public and political establishment would not have accepted it.

The grudging cooperation between Rabin and Peres continued until November 4, 1995, when Rabin was murdered by a right-wing extremist. The assassin could have killed Peres, but decided that targeting Rabin was the more effective way to derail the peace process. Succeeding Rabin, Peres tried to negotiate a peace deal with Syria on the heels of Oslo. He failed, called an early election, ran a bad campaign, and lost narrowly to Netanyahu in May 1996.

The next ten years were not a happy period for Peres. He lost the leadership of Labor to Ehud Barak, joined Ariel Sharon’s new Kadima party and his government, and was the object of criticism and attacks by the Israeli right, who blamed him for the Oslo Accords. Peres began to play down the Nobel Peace Prize that he had shared with Yasser Arafat and Rabin after Oslo. The discrepancy between his stature on the international stage and his position in Israeli politics became glaringly apparent during these years—disappearing, however, when he became President in 2007.

Peres was an experienced, gifted leader, an eloquent speaker, and a source of ideas. But perhaps most important, he was an Israeli leader who had a vision and a message. This was the secret of his international stature: people expect the leader of Israel, the man from Jerusalem, to be just that type of visionary figure. When the country’s political leadership does not meet that expectation, a leader like Peres assumes the role—and gains the glory.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israel’s last founding father

September 28, 2016