Editor’s note: Israelis will go to the polls on March 17 to elect the 20th Knesset, Israel’s parliament, which will then form a new government to replace Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current one (he hopes to head the next government as well.) We are following the run-up to the elections in a series here on Markaz, the blog of the Brookings Center for Middle East Policy.

With the dust settling on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s trip to Washington and his speech to Congress, the Israeli elections campaign enters its final week. This is a good opportunity to revisit the numbers and assess who has the best chance to form the next government in Israel. In a previous post, Who Will Win? (The Numbers, Take 1), I went through the main considerations in determining the winner. (A subsequent post, here, revisited the numbers more briefly, and so I’m treating that as “Take 2-ish”).

The upshot of it is that—barring the usual polling-day surprises—a national unity government of some form now appears to be the most likely outcome. This may, in fact, be a short-lived government tasked with electoral reform. Still, the elections are by no means over. A narrow Netanyahu government is possible and a big electoral surprise in the Center could even mean a Herzog victory. As noted previously, it appears that we will not know the winner of the elections on election night, but only after the horse-trading has begun.

A lot has happened since the previous post (be sure to see Lauren Mellinger’s elections news summaries, here, here, and here) but most of the action was not in the public polling, but rather in the realm of elite politics and jockeying.

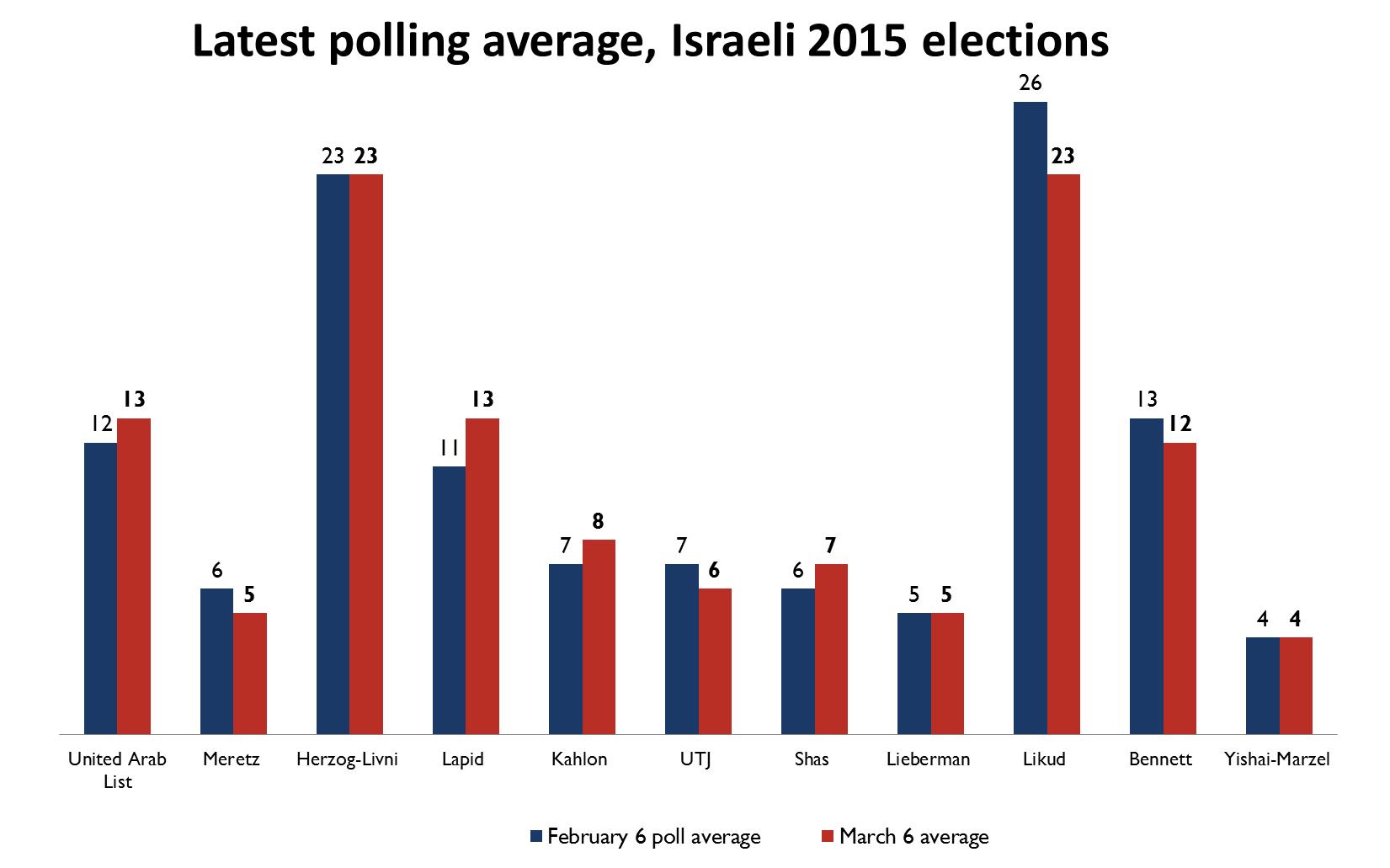

First, the raw numbers, taken from a simple 3-poll average by Haaretz (more sophisticated averages exist, but they tell a very similar story and their methodological assumptions are, at times, risky in a system with so many moving parts):

Figure 1

Overall, the numbers in Figure 1 resemble those of a month ago, though their interpretation differs somewhat. The Likud has lost some ground, mostly in early February. Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid has gained somewhat and has momentum, suggesting he may yet enjoy a last minute surprise, as he did in the 2013 elections, as Chemi Shalev notes. Naftali Bennett, on the other hand, has lost steam and no longer looks like the hero of the campaign—as he did early in the cycle—but in a narrow Netanyahu-led government he would still wield a great deal of power.

Did Netanyahu get a Congressional speech bump?

The initial polls after Netanyahu’s speech to Congress suggest he may have gotten a small (perhaps 2 seat-) bump. This, of course, could easily be a coincidence or statistical noise. Another recent poll shows a larger gain for the Likud, but again, causality is suspect. The politics of the speech, then, seem underwhelming at best.

To my mind, the spectacle of the speech was political gold, but I may have overestimated its political significance for viewers. The Iran issue and Netanyahu’s ability to speak about it in English are not news. For many Israelis, Iran—important as it is—is a distraction from the issues they care about more: the cost of living, the economy, social equity and social divisions inside Israel. Of course, it may well be that without the speech in Washington, domestic issues would have dominated the agenda even further, to Netanyahu’s detriment.

Either way the battle for the agenda is not easily won, even with a speech in Washington. (More on this battle of agendas will follow in the next post in this series.)

What has changed?

While the numbers are relatively stable, two important developments, both favoring Netanyahu, occurred in the party arena: Avigdor Lieberman, chairman of Yisrael Beitenu, announced he would not join a “leftist” (Herzog) government, explaining that it was unlikely anyway; and Arieh Der’i, the leader of Shas, declared his support for Netanyahu, albeit demanding a reformed Netanyahu from the days of the previous (secular-dominated) coalition.

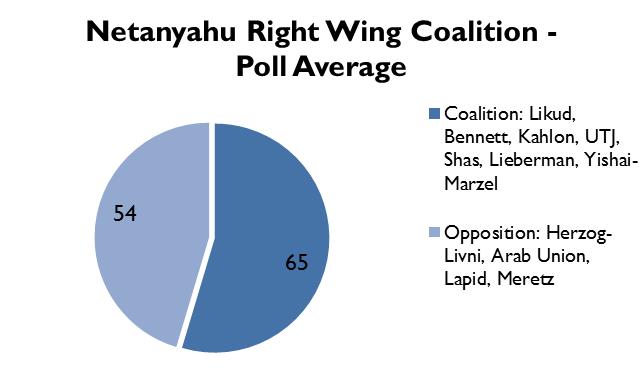

Thus, a narrow Netanyahu-led right-wing-and-religious government is certainly still possible.

Figure 2

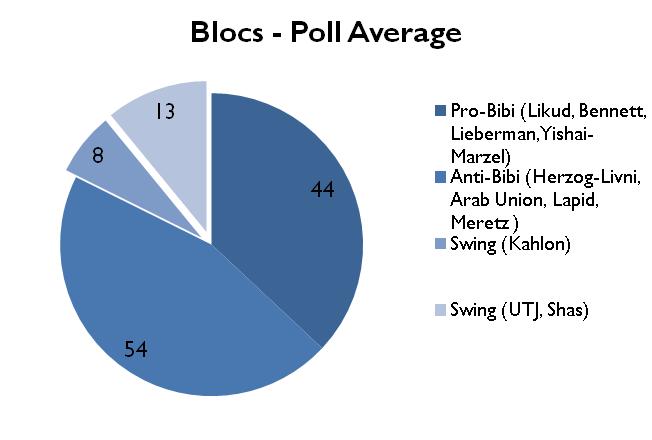

The key player in this scenario—indeed the kingmaker-apparent in these elections—remains Moshe Kahlon.

Figure 3

As Figure 3 shows, Kahlon is essential for either bloc to cross the 60-seat (50%) mark. Should he recommend Netanyahu to President Rivlin, the game is likely over, assuming Lieberman and the Ultra-Orthodox do not change their minds.

Should Kahlon choose to side with Herzog, or should Lapid or the Zionist Union outperform the polls dramatically, a Herzog coalition would be possible as well. As I noted previously, however, this narrow coalition would be hard to construct or maintain, as it would have to include both the Ultra-Orthodox and Lapid, and would still be razor thin.

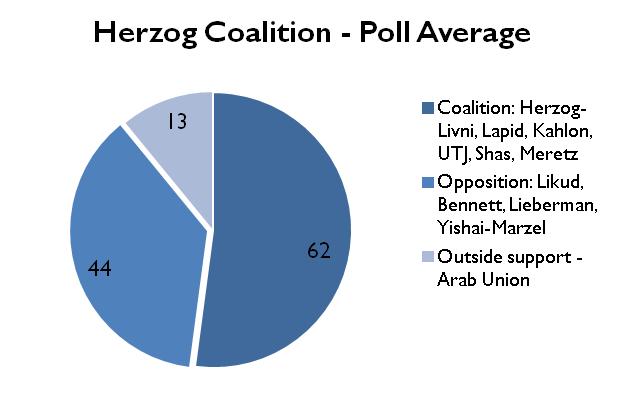

Figure 4

While Herzog could count on some outside support from the Arab Union, the Arab list is fractured and includes the nationalist Balad party, so extreme it could not even acquiesce to an agreement to share “surplus votes” (those that do not round up to a whole seat) with the Jewish-majority Meretz. Meretz includes an Arab MK, but Balad would not support an agreement with a “Zionist” party, as dovish as Meretz might be.

Thus despite the best efforts of the leftist elements in the Arab Union (primarily its pragmatic and charismatic head, Ayman Odeh of Hadash), the surplus of votes of the Arab Union will be lost to the Left-wing bloc. Moreover, with Meretz sharing its surplus votes with the Zionist Union headed by Herzog, Lapid’s party was left out in the cold as well, further costing the center-left bloc votes. This small but telling example shows just how far Balad is from participating in Israeli political life or from identifying with the dovish camp in Israel. If the Arab Union splits after the elections, Hadash (a genuinely pro-peace party with one Jewish MK, and which generally avoids nationalistic grandstanding) may play a more productive role, but it’s share of the joint slate (which consists of four parties) is limited.

The no-winner scenario

Kahlon’s own statements suggest he may well recommend no one—or himself—to the president. (He has said merely that whoever endorses his domestic agenda will get his recommendation.) Lieberman’s statements too, leave the door open to abstention at the president’s mansion. Widespread expectations are now, in fact, that Kahlon and Lieberman may join together to force a national unity government, with electoral reform high on its agenda.

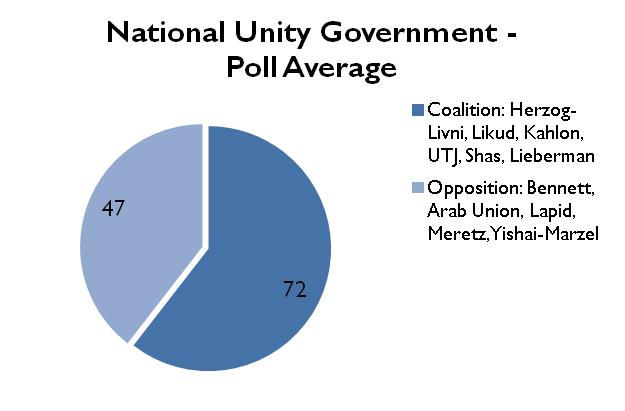

Figure 5

Indeed, Amit Segal of Israeli Channel 2 News reported that President Rivlin intimated he might go the same route—if neither candidate should garner 61 recommendations, he will invite both Netanyahu and Herzog to form a unity government tasked with changing Israel’s electoral system. These reforms may include designating the leader of the largest faction as the automatic prime minister, something which would greatly enhance the attractiveness of the larger parties to voters, increasing their dominance and, presumably, the ease of forming coalitions (for more on electoral reform, see the Israel Democracy Institute’s recommendations).

Who will win?

As the elections approach, and on election night, the first question to ask remains as before: Can Netanyahu garner 61 recommendations? If Lapid or the Zionist Union outperform the polls dramatically, there could still be 60 anti-Netanyahu MKs to block a Netanyahu government and give Herzog the first chance to form a government.

More likely, if the polls hold more or less, the spotlight returns to the center, to Kahlon in particular, to determine between a narrow Netanyahu-led government and a unity government of Netanyahu and Herzog.

“>

“>

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israeli elections: Who will win? (Take 3-ish)

March 9, 2015