Executive summary

An increasing number of financial market actors, including those in the private and public sectors as well as regulators, are reckoning with how to scale climate finance in rapid, cost-efficient ways that advance climate equity. While there is a body of research on climate finance for decarbonization, there has been comparatively little research on what role financial markets could and should play in advancing climate equity. There has been even less focus on U.S. financial markets and their subnational influence on the extent to which different regions, sectors, and demographic groups benefit from climate finance.

This report seeks to analyze these gaps, applying first principles of climate equity to the U.S. financial sector. It is intended as a high-level guide for federal and state policymakers as well as financial market actors to understand the principles, drivers, and constraints of climate equity. Financial markets are complex and made up of multiple organizations and regulators, and their composition can differ substantially between regions and sectors. Rather than depict each of these in exhaustive detail, this report describes financial market activity at a high level, asking where and how climate equity is being incorporated into public policy and private decisionmaking and the extent to which approaches to date are likely to advance more inclusive and effective climate finance. In so doing, this report shows that:

- The use of climate equity principles is still nascent within climate finance, especially at the subnational level. Attempts to advance climate equity have focused on process rather than outcome-based targets and have tended to deploy climate equity as a goal rather than a metric. Moreover, little is known about which combination of policies and targets is best for advancing climate equity nationally and within specific sectors.

- The underfinancing of adaptation and compensation for loss and damage is already creating inequities. Climate finance has focused on reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, at least in part because of the higher capacity for generating returns on investment, as well as the high relative level of international attention dedicated toward developing systems to measure emissions reductions rather than gains in adaptation. However, investments in adaptation and compensation will arguably produce greater gains in climate equity as well as economy-wide benefits, like reductions in public spending, that are more diffuse and more difficult to measure.

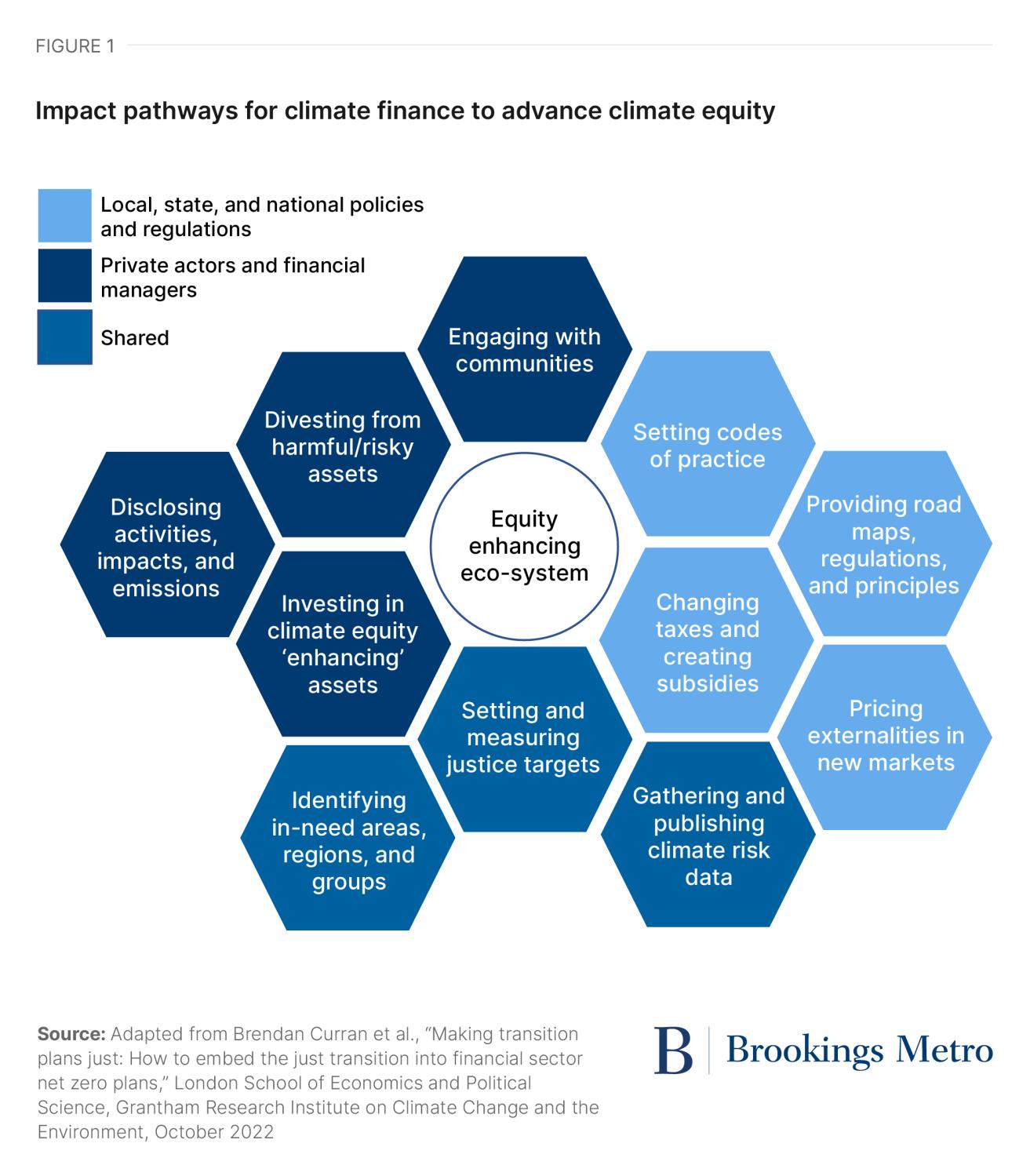

- Different financial market actors have different impact pathways to advancing climate equity. It’s unlikely that one component of markets alone, like private developers, has the tools, capacity, and incentives to advance climate equity. Rather, a combination of different mechanisms and goals across a range of private, public, regulatory, philanthropic, and other types of organizations is likely to be necessary.

Following this analysis, the report identifies several pain points—barriers likely to impede the adoption, and effectiveness, of more equitable approaches to climate finance. This includes the following barriers:

- Barriers in interpreting and applying the concept of climate equity, including difficulties in operationalizing climate equity as a measurable target, mismatches in financing scale and scope and climate equity impacts, and challenges in aligning the profit-oriented goals of financiers with social outcomes.

- Regulatory and governance barriers, including dependencies within financial markets that limit private and public sector capacity to advance climate equity, such as informational asymmetries and a lack of durable legislation.

- Logistical and political barriers, including the complexity of financial markets; regional variation in climate vulnerabilities, capital needs, and capacity; and the politization of climate equity and justice as a policy goal.

Introduction

The objective of advancing climate equity, defined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as the “goal of recognizing and addressing the unequal burdens made worse by climate change, while ensuring that all people share the benefits of climate protection efforts,” is smart policy. Tackling climate action in ways that prioritize equity can help to ensure that efforts to shift to a lower-carbon economy are more transformative, sustainable, and cost-effective. U.S. financial markets should be central to these efforts.

By influencing flows of capital across industries, technologies, regions, and sectors, an array of public, private, and philanthropic dollars and the laws and norms that govern financial markets are crucial to achieving rapid domestic decarbonization. Financial markets are pivotal to scale and deploy the lower-carbon technologies and finance investments in the built environment that are necessary to make communities more climate resilient. While other policy tools may be more effective at advancing climate equity, in the U.S. policy landscape where private capital and philanthropic organizations are a core pillar of action, capital and financial market regulation will have an outsized impact on how inclusive, equitable, and just U.S. climate action is.

Yet, presently, U.S. financial markets are not geared toward advancing climate equity. There are at least two separate, but related, challenges that are creating an environment for inequitable outcomes. First, financial markets are underfinancing decarbonization and adaptation, even as they continue to invest in fossil fuel–based technologies in ways that worsen inequities. A recent McKinsey report found that, to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the global economy will require $9.2 trillion in annual average spending on physical assets, an increase equivalent to half of global corporate profits today and one quarter of total tax revenue in 2020. Despite the real, and increasing, threat of climate risks devaluing assets and changing the profitability of investments in some sectors, technologies, and regions, the behavior of financial managers does not reflect these risks, and the laws and rules governing financial markets are not aligned to change this behavior. For example, in 2022, the U.S. provided an estimated $760 billion in direct and indirect subsidies to the fossil fuel sector, but the country spent only $2.3 billion in adaptation finance.

Second, policies and financial managers that have mobilized capital to flow to climate action are not targeting climate equity in transparent, consistent, and effective ways, and there are few incentives to change this behavior. The challenge is this: an overemphasis on rapidly scaling investments in climate action, while meeting decarbonization targets, excludes the most vulnerable, widening the inequities that already exist within the U.S. This fear is substantiated by the data. According to the U.S. Climate Finance Tracker, over the past 5 years, less than 11% of the total private, philanthropic, and government finance within the U.S. included the terms “justice” or “equity” (see Box 1).1 Where equity or justice is pursued, few public or private sector efforts have operationalized the concepts into actionable targets and metrics, with even the definition of equity varying considerably.

This report seeks to analyze these challenges, asking what operationalizing climate equity in U.S. financial markets would or could involve. Unlike other research on climate finance that centers private sector priorities of profit maximization and risk minimization, this report begins from first principles of climate equity. The first section begins by summarizing the current state of climate equity in U.S. financial markets, and the second and third sections go on to propose why and how the U.S. should adopt a more comprehensive approach. Finally, the fourth section identifies operational, logistical, and political obstacles to U.S. financial markets advancing climate equity.

Box 1: Defining climate finance as well as climate equity and justice

Climate finance: Internationally, climate finance is codified in Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement and is defined as “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilient development.” It includes investments in both adaptation and mitigation. Effective climate finance relies on a strong enabling environment, including a financial ecosystem with transparent and consistent rules; accessible data; and low political, regulatory, macroeconomic, and business risks.

There are two other important climate finance concepts relevant to equity: “additionality” and “common but differentiated responsibilities.” Additionality means that capital labeled as climate finance should demonstrate that outcomes are additional to what would have happened otherwise, and common but differentiated responsibilities means that, while all parties have an obligation to address climate change, responsibilities should differ according to capacity and responsibility for emissions.

Climate equity and justice: According to the EPA, an equitable outcome for climate policy is one where everyone regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, or income has the right to the same environmental protections and benefits, as well as meaningful involvement in the policies that shape their communities.

However, climate equity is a dynamic concept, having no standard definition within the U.S. or internationally. What counts as an equitable outcome varies depending on the geographic scale, type of project or policy, the region and sector where outcomes are measured, and whether the focus is on GHG emissions, health, biodiversity, or another outcome. These dynamics make advancing equity a more complex goal than policy objectives like GDP growth or inflation reduction.

Definitionally, equity is distinct from equality. While equality implies that all people and groups should be treated the same, equity acknowledges that real differences and barriers exist between demographic groups along lines of income, race, ethnicity, and/or gender, for example. Equity means that these barriers warrant policy action to ensure that all individuals and communities have the same access to opportunity irrespective of their background or identity. In an unequal society like the U.S., where some of the wealthiest households earn 12.6 times more than the poorest households, policies premised on equality can lead to inequitable outcomes.

Equity is closely related to the concept of justice. While the two are frequently used interchangeably, the pursuit of climate justice can be considered a component of advancing climate equity. This typically involves three connected elements: distributive justice, procedural justice, and recognition. Distributive justice means that the distribution of costs and benefits of climate impacts or the outcomes of a policy change are fair. Procedural justice entails the inclusion of a diverse group of stakeholders in decisions that affect them. Finally, recognition involves the acceptance of underrepresented and marginalized groups as legitimate stakeholders in social and economic decisions. The application of these principles in policy calls for:

- historic analysis of environmental/climate injustices in a given region;

- the identification of populations for whom there is a reasonable disparity;

- the consideration of justice at each stage of an intervention (including development, implementation, quality management, and outcomes);

- and the meaningful inclusion of historically marginalized groups in decisionmaking that affects their communities.

How is climate equity pursued across financial markets internationally and within the U.S?

In international policy, there is an increasing commitment to justice as a tenet of climate finance

There is a growing appetite among policymakers and private sector organizations to include climate equity and justice as guiding principles for international financial markets. International development organizations like the World Bank Group are at least nominally centering climate equity in their action plans, while investor-led initiatives, like Climate Action 100+ and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, have signaled justice as an important goal in efforts to finance net-zero emissions targets.

In 2015, climate justice was adopted as a principle of international climate finance in the Paris Agreement, and the concept has since helped guide the establishment of the Green Climate Fund and the Loss and Damage Fund. These international agreements have used climate equity principles to assess the distribution of funds between nations. This has included, for example, recommendations that nations with high GHG emissions subsidize the decarbonization of low emitters and help offset the costs of disaster-related asset losses. However, some groups of nations have advocated for further-reaching efforts to restructure international financial systems, including through national debt cancellation and climate reparations. Conversely, for adaptation finance, justice and equity have been sparingly, and inconsistently, applied. While there are some promising signs that private investment in adaptation is growing, including through blended public-private financing, it remains an underexplored area.

Developing outcome-based climate equity metrics and systems to track progress is a core concern. In particular, accurately identifying climate finance remains a challenge, particularly across corporate targets and international development funding. Moreover, there are few examples of subnational attempts to incorporate climate equity into financial markets, although those that have legislative mandates for climate action, like the United Kingdom (UK), appear to be more successful at accelerating domestic climate finance.

Climate equity is nascent in U.S. financial market policy

While the U.S. has no legislative mandate for climate finance, policymakers have increasingly used climate equity and justice as part of national, state, and city-level climate action plans. These plans have included, for example, provisions to direct climate finance toward historically marginalized or vulnerable communities. Overall, U.S. lawmakers, particularly at the national level, have provided incentives rather than regulations to influence the scale and direction of climate finance. However, mobilizing climate finance, let alone climate equity, is still a nascent goal for the private market and the financial market regulators and ratings agencies that assess investment risks.

At the federal level, there have been several attempts in recent years to deliver climate finance in more equitable ways through executive orders and legislation alike. One key example is the Justice40 Initiative, which mandated that 40% of federal climate funding is allocated to underserved communities. Other important ones include the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which ringfences applicants for resilience from vulnerable and historically marginalized areas); Solar for All, which enables over 900,000 households to access solar energy; and Community Disaster Resilience Zones, which designate highly vulnerable areas to crowd in private investment. The federal government has also tried to develop a stronger ecosystem for private capital mobilization, including funding for technical assistance centers to enable under-resourced communities to attract philanthropic and private funding for climate projects. On the other hand, national climate policy has also used financial incentives in regressive ways. Critics have targeted the use of tax credits for housing weatherization and electric vehicles, for example, for enabling wealthier households to adapt earlier at public expense.

From a climate equity perspective, state and local policies arguably have the largest impacts for households and communities. City-level governments have implemented climate justice and equity plans, including ones that leverage private sector climate finance. Over the last 10 years, city-level plans that include climate equity or justice have increased and become more rigorous: 40% of major cities that have climate action plans include equity goals, and 35% of them have measurable indicators, according to one study. The federalist U.S. system, which enables state and local climate policy experimentation, can provide policy blueprints for federal decisionmakers. However, this system has also created a patchwork of planning, with some of the country’s most vulnerable places, like Texas and Louisiana, having the least comprehensive climate plans.

Approaches to climate equity are limited to principles rather than targets

Despite this progress, private and public sector initiatives to advance climate equity in financial markets have focused on principles rather than a rubric to guide climate action by setting impact targets. The financial sector has struggled to mobilize climate finance at all, let alone to advance climate equity. A recent study showed that only 36% of corporate standards and voluntary initiatives on net-zero emissions, for example, included a consideration of equity or justice. The corporate sector is now abandoning many corporate targets, illustrating their lack of durability in influencing long-term changes. The private sector has largely followed an avoiding- financial-risk approach, characterized by initiatives on disclosures that emphasize justice as a component of corporate process and strategy rather than as an outcome. This has made it difficult to track outcomes and can enable private actors to signal credibility without tangible changes in lending or investment practices.

Why advancing climate equity should be a goal of U.S. financial markets

Climate finance can help to equitably distribute climate risks and impacts

Direct climate impacts, like climate-related disasters, that result in the loss of assets and property; the indirect impacts of climate change (including increases in costs such as utility bills, healthcare, and insurance premiums); and the increased volatility of markets, including for labor, pose a greater threat to those living precariously. By investing in technologies and sectors to ease these impacts, and by divesting from the technologies and sectors that amplify them, climate finance can minimize the risks that these households and communities face.

The failure to adequately price climate risk is already jeopardizing the financial security of the most vulnerable. U.S. financial market regulators do not mandate climate risk or emissions data disclosures, and financial actors themselves have been slow to include climate risk when assessing the strength of investments. This is true for national regulations on financial exchanges—imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—but it also applies across the various subsectors of financial markets where physical public and private assets are exposed to climate risks. There is no legislative mandate, for example, to disclosure wildfire or flood risk when selling a home, and where publicly available information does exist, it is frequently outdated, underestimating current risks. These information gaps can result in developers investing in high-risk and/or resource-constrained areas where long-term viability for high-density habitation is economically prohibitive or unviable. Coastal cities, for example, can face hard limits to adaptation, where engineering solutions to prevent land loss may be impossible. These informational asymmetries and the lack of risk signals for developers are already leaving vulnerable communities open to perverse outcomes that can further entrench inequities.

Finally, prolonging the tail end of fossil fuel extraction involves health and financial risks that are already producing inequitable outcomes for communities living near these industries’ facilities. Fossil fuel infrastructure itself, in addition to providing employment to some regions and communities, also comes with higher rates of toxicity in neighborhoods alongside these industries. Researchers have long documented how these communities are overwhelmingly low-income and, in most cases, majority non-white. Moreover, as the U.S. shifts away from a fossil fuel–based economy, communities dependent on extractive industries can become “stranded,” as other regions and communities benefit from investments in renewables. As more fossil fuel–based energy sources are retired, the remaining assets can become a burden for local communities, excluding local residents from job opportunities or investment that might have otherwise occurred.

But climate finance without an equity framework is not guaranteed to deliver more equitable outcomes

However, scaling financial markets to meet the financing needs of climate mitigation and adaptation is not enough. Because the impacts of climate change are not just a product of exposure and because they are mediated by social factors—like wealth, access to health care and social services, and housing quality—lower-income and historically marginalized households typically have a lower adaptive capacity than other households. Without strategic investment, transition policies themselves could amplify these patterns of social inequity, including by:

- worsening the distribution of negative externalities through maladaptive investments,

- imposing undue transition costs on vulnerable groups,

- underinvesting in communities with high needs but low capacity to absorb capital,

- excluding historically marginalized groups from decisionmaking around land use,

- and excluding vulnerable groups from the benefits of climate action, like local job creation or access to cost-effective and safe technologies.

These concerns are warranted. Internationally, patterns have already emerged that suggest that climate finance is flowing to the most bankable, lowest-risk, highest-return, and largest-scale projects, which tend to exclude those most in need. Moreover, the U.S. has a poor track record of improving environmental quality and advancing equity. Aggregate improvements, like the roughly 70% reduction of aggregate emissions following the Clean Air Act, have occurred over the same period that exposure to air pollution and known carcinogens have stayed consistent or worsened for disadvantaged communities. While increasing financial risk and market volatility are compelling motivations for action at a macro level, at the level of individual corporations, there remain financial risks to taking early action. While mission-driven and public sector financing can help to overcome this challenge, these capital sources, too, have historically fallen short of bridging financing gaps between under- and over-resourced communities.

There are good economic reasons for financial markets to advance climate equity

The potential for inequitable outcomes offers motivating, compelling moral reasons why financial markets should consider climate equity. However, setting these aside, there are also at least four economic reasons why financial markets should be central to advancing climate equity.

- First, flows of capital have consequences for how inclusive and just U.S. society is. When equity is not a consideration in policy and practice, capital has tended to flow in ways that create or compound inequities undermining other policy objectives and increasing social costs.

- Second, asset managers and investors have a fiduciary duty to consider climate risk. Financial markets actors, like the managers of pensions and investment funds as well as regulators, make decisions based on the interests of their constituencies. Properly incorporating climate risks into investment decisions reflects the best interests of the investors these market actors represent and the long-term financial stability of their investments.

- Third, incorporating justice and equity targets can make climate policy more durable and can reduce the risk of maladaptation—action that enhances climate resiliency for some groups at the expense of others. Incorporating justice and equity targets into decisionmaking by engaging affected communities can minimize this risk by closing informational gaps. Moreover, bundling social policies, like opportunities for job training or income subsidies, with decarbonization policies can ease the adjustment burden, ensuring that transition policies are sustainable across administrations.

- Fourth, investments in climate resilience can involve co-benefits that reduce private costs. Cleaner infrastructure, such as nature-based solutions, can deliver wider benefits, like reducing the potential cost of loss and damage during climate-related disasters.

What are the impact pathways for U.S. financial markets to advance climate equity?

Investing in climate action and adequately pricing climate risks are necessary, but not sufficient, steps to ensure that financial market activities advance climate equity. Because financial markets allocate capital across neighborhoods, regions, cities, sectors, industries, and businesses, a central question at the national level should be who (which industries and regions) are prioritized in the distribution of scarce funds. However, given the influence that financial markets have in accelerating or constraining climate action, considerations of climate equity can, and should, be wider than ensuring fairness in access to funds.

Climate equity implies more, including efforts to identify historically marginalized groups or regions; alter market behaviors; or targeting policy, actions, and/or public investments to ensure that those people and places are protected from the impacts of climate change and are not excluded from the benefits of the climate transition.

Potential national goals that should be considered include:

- reducing the loss and damage of direct and indirect climate impacts on vulnerable groups by divesting from harmful industries (especially in overburdened areas) and ceasing investments in assets and corporations that contribute to global warming and/or environmental degradation,

- reducing the costs of adaptation to vulnerable groups and providing opportunities for them to benefit from transitions through employment opportunities, access to cleaner and cheaper energy as well as safe and affordable housing, and

- helping to grow the power of marginalized groups to participate in climate action through representation in decisionmaking that affects them.

Starting from these goals, this section maps the potential, high-level impact pathways across financial market actors, identifying the different constraints and opportunities for advancing climate equity.

An ecosystem of organizations—with differing constraints, responsibilities, and opportunities—influences how financial markets impact climate equity

Financial markets are part of an ecosystem of organizations with varied capacities to take on risks, fiduciary duties, internal goals, and legislated responsibilities. Different types of actors—including regulators; insurers; ratings agencies; banks; developers; and state, city, and federal governments—collectively alter the flows of money by way of their regulations, policies, and behavior. Each of these actors has a different role to play in ensuring that financial markets collectively advance climate equity. While these roles can be highly specific to the industry, sector, or project in question, at a high level there are at least two dynamics that will influence how organizations engage with climate equity.

First, most private sector organizations select investments based on returns, and these selections don’t always align with climate equity priorities. Climate finance can be separated into three buckets according to its profit- generating potential and capacity to contribute to climate equity:

- Investments that contribute to mitigation: These are investments in technologies like renewable energy or other utilities, which decrease the country’s GHG emissions. These activities have a high potential for profit generation.

- Investments that contribute to adaptation: These are investments in technologies and infrastructure designed to help individuals and communities adapt to the impacts of climate change. These investments are likely to include a mix of projects with significant profit-generating potential (such as those in the housing sector) and projects with little profit-generating potential (such as sea walls), the latter of which will require some amount of public sector support.

- Financial compensation for loss and damage: This includes funding that offsets the loss and damage of direct and indirect climate impacts. These are likely to not be profit-generating and will require public sector support.

Second, project (or implementation) finance has more direct impacts on climate equity than non-project (financial instruments and assets) finance. However, financial markets remain dominated by the management of financial assets concerned with generating a return on investment rather than maximizing social outcomes. This mismatch in capital scale and financiers’ objectives can lead to the under-provision of implementation finance, undermining attempts to mobilize private capital for climate action.

These dynamics mean that, from a climate equity perspective, the private sector alone is unlikely to be capable of driving climate action in ways that advance equity. Rather, equity and justice frameworks for climate finance should aim for consistency, meaning that the behavior of individual organizations is aligned with a national or international climate goal.

Different financial mechanisms will have different implications for advancing climate equity

In addition to these overarching dynamics, different types of financial market actors also have unique limitations regarding the types of mechanisms and behavioral changes available to influence climate equity. For simplicity’s sake, Figure 1 considers these impact pathways for the private and public sectors. In reality, financial markets are more complex, with nuanced opportunities and limitations relevant to different sectors and actors.

The private sector can influence climate equity by providing risk and impact disclosures, including the climate credentials of their partners, and by altering risk, engagement, and capital allocation strategies to align with decarbonization targets. In contrast, financial market regulators and policymakers, who set the rules of financial markets through changes in legislation and regulatory fiat, can set standards and codes of practice; create incentives through taxation and subsidies; and develop local, state, or national targets for climate action and equity. Some mechanisms, like identifying under-resourced communities and publishing climate risk data, are shared impact pathways.

These pathways impact how climate equity is defined and operationalized. A corporate target, for example, might involve indicators for the rate and extent of divestment from fossil fuel producers and the depth of community engagement, while federal regulations could mandate targets for reductions in social vulnerability or climate risk exposure in certain regions or across specific groups.

At a more granular level, climate finance mechanisms can be broken into tools accessible to private sector actors (like corporations and hedge funds); financial regulators, including local, state, and federal agencies; and national regulators that influence the flow of capital through the rules and policies of entities like the SEC.

Examples of private sector tools and practices include:

- Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funds and ratings, which assign a price signal to corporations for their performance on ESG outcomes;

- Green exchange-traded funds, which are publicly traded investments in companies that support or are involved in environmentally sustainable technologies or products like renewables;

- Corporate social responsibility (CSR), impact investing, and mission-driven corporate strategies, where capital managers target investments toward a region or cause to generate a social or environmental good;

- Disclosing corporate climate impacts and activities including, for example, direct impacts like GHG emissions but also corporate activities that indirectly affect mitigation and adaptation like investment principles and investees; and

- Divestment and relationship management, including divesting from high-emitting assets or businesses and building partnerships with businesses and organizations with a greater capacity for positive environmental or social impacts.

Examples of financial regulations and government tools and policies include:

- Policies that crowd in investment, including by designating priority areas for investment, subsidized through grants (the Opportunity Zones model) and by providing tools that identify vulnerable areas or groups (such as the Council on Environmental Quality’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool);2

- Regulating disclosures and zoning, including by mandating reporting of corporate GHG emissions and the financial risk of climate impacts by region and by passing legislation that influences land use (such as zoning provisions to avoid cumulative impacts in overburdened areas);

- Corporate and individual subsidies or changes to taxation to influence the uptake of new technologies that have a positive climate impact or assign a price to negative externalities (through tools like a carbon tax);

- Providing national guidelines, targets, and roadmaps, including national emissions reduction targets or climate investment targets that specify timelines and federal expectations for corporate partnership; and

- Direct public funding by establishing, for example, a national climate resilience or adaptation fund, similar to the federal spending on disaster relief.

Some mechanisms are shared or pertain to public-private partnerships, including:

- Green and environmental impact bonds, which assign a green label to debt-equity funding for projects with a net-positive environmental or climate impact. Bonds are issued by municipalities or private actors to raise equity, typically for infrastructural investment and

- Green banks, which offer lower-cost options to finance climate investments.

Each of these mechanisms has implications for climate risks and equity, including for the mechanisms’ efficacy at achieving their stated goals, cost-effectiveness, and risk of maladaptation. Moreover, many of these tools are related to or dependent on each other. For example, public sector mandates to publish climate risk data can enable more effective corporate climate strategies. Finally, climate finance is still a relatively new field. Little is known about the relative merits of each approach, especially over the long term.

Barriers to advancing climate equity in U.S. financial markets

There are several barriers likely to create difficulties for efforts to advance climate equity through U.S. financial markets. Following from the complexity of the financial sector, constraints and opportunities along impact pathways, and the nascent engagement with climate equity to date, these barriers can be broken into three areas:

- Barriers in interpreting and applying the concept of climate equity,

- Regulatory and governance barriers, and

- Logistical and political barriers.

Barriers in interpreting and applying the concept of climate equity

Financial markets have relied on process, rather than outcomes-based climate equity metrics

Operationalizing climate equity requires metrics that correspond to real and measurable outcomes, not just changes in process. However, this has been a persistent challenge, especially for the private sector. Corporate strategies for climate equity have tended to focus on changing internal processes, like improving the transparency of investment decisions. Because these metrics are designed to measure changes in business operations rather than outcomes, they can have little correlation with actual changes in inequities, or even climate impacts. In the worst cases, process-based targets can reward inaction.

ESG, arguably the most direct tool that financial managers currently use that impacts climate, demonstrates these challenges. A 2020 study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that evaluated the climate impacts of companies with a high environmental (E) score found that the highest scoring companies also had the highest carbon emissions. A business’s E score was driven primarily by company size and disclosure activity rather than environmental performance. While ESG ratings are not designed to only measure climate impacts, they highlight the difficulties of capturing complex information like equity using a performance index. While it is arguable that this challenge could be overcome through more accurate data, process-based mechanisms will always only indirectly capture performance.

The scale, scope, sector, and type of finance shapes how climate equity should be measured

Relatedly, the scale, scope, and sector of financial investments shapes the operationalization of climate equity. The identification of measurable equity indicators and targets will depend on the project, the type of climate action, and the intended outcomes. In many cases, advancing climate equity will inevitably mean balancing between investment priorities across different scales, sectors, and regions.

Moreover, there is not always a direct relationship between the project and impact scale. Investments in physical assets, like funding renewable utilities across a city, for example, occur at a higher scale than many of the relevant impacts like changes in household costs. Mismatches in project and impact scales can also create challenges in identifying a relevant target group. As climate impacts unfold across a diverse range of different groups and communities, there will be situations where equity priorities across scales are in conflict—like, for example, maintaining equity in federally provided climate resilience funding between states to the detriment of pursuing equity between racial groups nationally.

There is a lack of publicly accessible data on climate risks, impacts, and vulnerability, as well as a lack of expertise in the financial sector to interpret this data

Equally important is transparent data on climate risk and vulnerability. With limited information on the environmental and climate performance of corporations and developers, it is difficult to determine which types of corporations or assets are aligned with climate equity targets.

There is also little information on social vulnerability. Ultimately, targeting climate equity requires identifying an impacted group and evaluating its exposure and vulnerability to climate threats, and this requires disaggregated data on vulnerability. Relatedly, there are skills gaps to interpreting climate risk and social vulnerability data. Investors and ratings agencies may not possess the skills necessary to interpret complex climate data or to understand how to communicate this data to impacted communities.

For some actors, the structures and incentives undergirding the financial sector are in conflict with climate equity

For many private actors in the financial sector, particularly asset managers, there is an inherent pressure to default to short-termism rooted in the structure of the market. This means that investments in climate equity that are harder to value—like investments in adaptation, for example—are likely to be underprovided compared to quick investments with high returns.

Relatedly, unlike in sectors where there are shared underlying assets, like construction where developers use the same critical supply chains or labor pools, in financial markets, many lenders and investors are removed from the underlying assets that they are lending against. This reduces the incentives for collective action among competitors and undermines the shared sense of success or failure that helps to drive a meaningful commitment to social equity.

Regulatory and governance barriers

Financial markets lack predictable signals, rules, and regulations for climate equity

Consistent and durable legislation helps create an environment that incentivizes climate action in just and equitable ways. Some nations and regions with clearer climate regulations, like the UK, have had greater success at reducing emissions, and there is some early evidence that these laws may also aid in mobilizing capital for climate investments, particularly from the public sector. Laws are also important for channeling investments to sectors, technologies, and industries more likely to generate positive social and environmental impacts while minimizing the risk that investments will produce negative externalities. At least part of the reason that financial markets have continued to invest in fossil fuel extraction despite the low cost of renewables, and by extension have risked stranded assets and increased the threat of loss and damage from direct climate impacts, is because the U.S. regulatory environment has not provided clear investment signals.

Financial market complexity, especially in project development, creates opportunities for inequities

Investments and financial products and instruments are complex. Diverse arrays of stakeholders across sectors are required to finance projects, including at different stages and for different purposes. This chain of actors can complicate efforts to ensure equitable outcomes. Actors joining at different stages in the investment process to build climate-resilient infrastructure, for example, may alter the capacity to track equity or introduce structures where inequitable outcomes are more likely. This is especially likely during the construction phase, when financiers with short-term priorities for profit generation may apply pressure to weaken more expensive project elements designed to deliver more equitable outcomes.

Some of the largest gains in climate equity are likely to come from low-return investments

Adaptation and compensation finance are arguably the most important investments for climate equity, but the private sector has fewer incentives to pursue these projects. While some investments and technologies can be bundled with adaptation to include climate co-benefits (like weatherizing homes), others (like changes in land use to protect communities from climate disasters) will require a larger role for the public sector. Other types of climate finance with direct positive impacts on equity, like funding for disaster losses and damage, are likely to fall almost entirely outside of the private sector.

Logistical and political barriers

Different financial mechanisms have unknown impacts on climate equity

The approach to mobilizing capital alters who is impacted, in what ways, and how benefits and costs are distributed, yet little is known about which mix of mechanisms can advance climate action in the most equitable ways. Debt-based financing (such as green bonds), for example, can create new obligations of debt servicing for city governments that can be passed on to consumers and workers in inequitable ways. For instance, after New York City used green bonds to finance Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) repairs after Hurricane Sandy, the city increased fares to service the new debt. These higher fares raised the cost of living for lower- income communities, who comprise a majority of MTA users, and the increased prices also contributed to layoffs for the largely working-class staff as total MTA ridership decreased.

Similarly, policy tools that incentivize the flow of capital into new industries, regions, and sectors without mechanisms to ensure a more equitable distribution can create unintended outcomes. An investment environment where investors avoid areas with higher climate vulnerability because of the risk of lower returns could create a system where capital flows to the places that can offer the highest returns, but not necessarily those with the greatest need. This phenomenon has been documented in other attempts to distribute private capital to help achieve social outcomes. Community development funding, for example, tends to flow to already well-resourced communities, as “the typical large county receives 1.25 to 4 times what the typical small county receives.” While mission-driven investors can offset some of these gaps, they tend to focus on smaller projects meaning that under-resourced communities can still miss out on the most transformative investments.

The most vulnerable communities face capacity challenges in attracting and using investment dollars

Communities have varying levels of capacity to absorb and use investment funds. These differing capacities can produce disparities when communities compete to attract climate funding. The lack of technical assistance and the under-resourcing of government agencies and civic organizations, for example, has helped to perpetuate a growing gap between wealthier and poorer communities after extreme disasters like severe flooding or hurricanes. Moreover, other more innocuous elements of historic economic development can also impact how and where climate funding flows. Unlike higher-density economies—like those of Europe, for example—the U.S. has underinvested in foundational infrastructure, like sanitation and transportation infrastructure. This can raise the cost of more transformative investments that would require building out networks.

This means a strong ecosystem of partners who understand local challenges and climate risks is required to ensure that climate equity is considered as projects are developed, financed, and implemented. This would include, for example, mission-driven investors, technical assistance agencies (which can help to attract government and philanthropic funding for climate resilience), and local financial institutions that have a better understanding of local risks.

The concepts of justice and equity themselves are politically controversial, and bipartisan initiatives for climate finance are underdeveloped

In the U.S., justice and equity are increasingly seen as part of a left-leaning political agenda rather than components of more efficient and cost-effective policy. For public sector financing, this can erode the capacity to establish and sustain consistent goals between administrations, while for the private sector, politicization of investment behavior can spook actors into inaction. Currently in the U.S., even market-based incentives for climate action have come under scrutiny, including most recently ESG.

Relatedly, by necessitating the identification of historically marginalized groups, pursuing climate equity is likely to involve contestation over which regions and communities benefit from investment or policy changes. This has already occurred to varying degrees. Notably, recent contestation over the use of race and ethnicity as a criterion for identifying historically marginalized communities has resulted in legal action against nonprofits, and even national agencies including the EPA and the Small Business Administration. In the long run, advancing climate equity in financial markets will require sustainable bipartisan support for justice and equity as integral components of effective policy.

Conclusion

As financial sector actors, ranging from private investors and asset managers to decisionmakers and regulatory agencies, look to deploy more capital toward climate action, public policies and corporate mechanisms can help to ensure that this happens in ways that prioritize equity. While there is a clear desire to take more just action, moving climate equity from an ambition to measurable targets remains underdeveloped. An immediate concern is the extent to which public and private sector finance will flow toward adaptation and compensation for loss and damage from disasters relative to mitigation.

Future work should develop national and state strategies for climate equity as a target for financial markets, and such work should identify realistic objectives for different types of financial market actors across sectors. Specifically, future research for U.S. climate finance policy could include:

- developing sector-specific metrics to track climate equity,

- assessing the distributional consequences of different types of corporate actions and public policies to advance climate equity,

- crafting quantitative tools to identify and map vulnerable and/or under-resourced communities,

- formulating policies to mandate government and corporate disclosure of climate risks, and

- identifying bipartisan actions on climate finance and climate equity to develop a more politically sustainable policy architecture across scales of governance.

Pursuing research in these areas can help to ensure that U.S. financial markets not only scale to meet the challenges of climate change but also do so in ways that reduce inequities.

Equitable climate finance series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Funding for this research was provided by HSBC Bank USA, N.A. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- This 11% figure was derived by selecting all finance that mentions the terms “justice” and/or “equity” in the project descriptions using the Climate Finance Tracker.

- The Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool was designed by the Council on Environmental Quality to enable federal agencies to identify disadvantaged communities for the provision of federal climate finance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).