Selecting their running-mates is one of the few things over which presidential candidates have near-complete authority. In making their selection, they reveal what they think contributes most to victory—and what they believe would be most helpful for their administration if they win.

In between his appearances in court, Donald Trump has been having a look at potential vice presidents. As with previous candidates, Trump faces an array of strategic choices.1 In 2016, with a personal life that was not exactly straitlaced, he decided that he needed someone who could shore up his credibility with social conservatives—especially evangelical Christians, who constituted a key bloc of the Republican Party’s base. Mike Pence was the right man for this job. Eight years later, Trump’s standing with this group is impregnable, so he can turn his attention to other considerations.

Option #1 is to broaden his appeal beyond his base of working-class white men by picking either a candidate from a minority group or a woman (or, as Joe Biden did in 2020, someone who checks both boxes). Candidates who could fill this role include South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott and Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who served as his press secretary. Another possibility in this category would be Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, who might galvanize Hispanics, a group already moving in Trump’s direction. To be eligible, however, Rubio would have to change his residence to another state, because the 12th Amendment to the Constitution prevents the selection of a president and vice president from the same state.

Option #2, the reverse of option #1, is to pick a nominee who reinforces his message and identity. The most recent example of this was Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, a young moderate Democrat from a southern state who chose Al Gore, another young moderate Democrat from a southern state, in 1992. The conventional move would have been to pick a veteran politician from another wing of the Party, as Michael Dukakis did with Lloyd Bentsen in 1988. By doing the opposite, Clinton underscored the generational contrast with incumbent president George H.W. Bush and drove home the message that his administration would seek to change the Democratic Party as well as the country.

If Donald Trump chose to go down this road, he would select someone who represents the transformation of the Republican Party that he has sparked—Ohio Sen. J. D. Vance, for example. A pick along these lines would also minimize conflict within his administration and give someone who shares his vision a running start for the 2028 presidential nomination.

Option #3 is to pick someone Trump regards as able to help him carry out his agenda after he is elected. This is what Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter did in 1976, when he selected Sen. Walter Mondale to serve, in effect, as his governing partner, although in choosing Mondale he also sought to bring in more of the liberal side of his Party. In 2000, this is what George W. Bush did in picking Dick Cheney as his vice president. Cheney, from the small and solidly Republican state of Wyoming, brought few electoral advantages but enormous governmental skill and depth. As a young first-term senator, Barack Obama went down the same road by picking veteran senator Joe Biden and entrusting him with significant policy and political tasks, including handling negotiations with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell.2

In Donald Trump’s case, a choice along these lines would send two messages—first, that he is confident enough about the election to choose someone who doesn’t add much politically to the ticket and second, that he recognizes the need for a partner to help him execute a policy agenda broader than the one he brought into the White House in 2017. The prime example of such a candidate is North Dakota governor and former presidential candidate Doug Burgum, whose star appears to be rising3.

The final strategic option is to use the vice presidential nomination to heal a divide within the Party. This is what Ronald Reagan did in 1980 by choosing George H.W. Bush, who famously dismissed the centerpiece of Reagan’s domestic plan—supply-side tax cuts—as “voodoo economics.” In making this choice, Reagan signaled his awareness that as a western candidate with some views outside the mainstream, he would need to reassure the traditional wing of the Party that he wouldn’t be a factional candidate and would remain open to their views. (His selection of James Baker, Bush’s campaign manager, as his first chief of staff reinforced this message.)

Trump could execute this move by choosing former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, his toughest primary opponent and harshest critic, as his running mate. As in all such cases, each would have to explain away what he or she had said about the other during the primary campaign, a maneuver that has long distinguished skilled politicians from rookie wannabes.

Although Haley would be Trump’s most surprising choice, she represents a reality that Trump and his political advisors would be ill-advised to ignore—namely, she continued to garner about 20% of the primary vote even after she suspended her campaign. She represents a demographic within the Party—college-educated, more upscale, and suburban rather than rural and small town—that continues to harbor reservations about Trump’s hard-edged brand of nationalist populism. As of yet, there is little evidence that many of Haley’s supporters would switch to Biden, but some might quietly withdraw from the fray and stay home on November 5. Trump may want to take out insurance against the possibility that the race will tighten in the fall. However, his desire for total control and obsession with vengeance would make such a move difficult for him despite its political advantages.

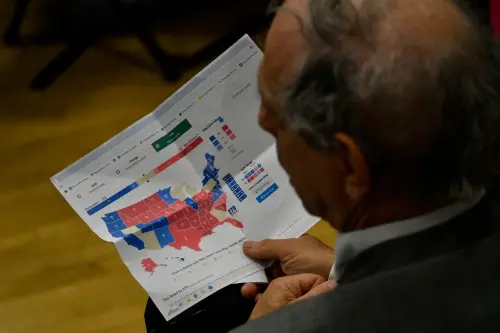

Politically, these four options divide into two groups. Options #2 (doubling down) and #3 (the governing partnership) would reflect Trump’s judgment that he has the general election in the bag and can focus on the future of his administration or governing philosophy. By contrast, options #1 (broadening the base) and #4 (healing the divide) would send the signal that he regards the outcome as uncertain enough to warrant a more cautious course.

Which way will Donald Trump go? I don’t know, and I’d bet that he doesn’t either. But two things are clear. First, his choice will reveal a lot about how he assesses the race. Second, as a master showman who knows how to get and keep the public’s attention, Trump will build suspense by delaying his choice as long as possible. In 2016, Trump didn’t announce his choice until three days before the start of the Republican National Convention. Expect a repeat performance.

-

Footnotes

- See Elaine C. Kamarck, “Picking the Vice President,” Brookings, July 2020. For a history of the evolution of this process. https://www.brookings.edu/books/picking-the-vice-president/

- Obama famously responded to the suggestion that he have a bourbon with McConnell by asking rhetorically, “Why don’t you have a drink with Mitch McConnell?”

- https://www.wsj.com/politics/elections/doug-burgum-trump-vp-shortlist-e41a2b45?page=1

Commentary

How will Donald Trump pick his vice presidential candidate?

June 5, 2024